I stepped off the long-distance bus with my bulging backpack. A big-eyed kid of about eight flourished a yellow sign in English in front of me, advertising cheap lodging in a family home, so I followed the kid to score a hammock for my first night in Coro, Venezuela. My friend Terry had accompanied me at the beginning of this trip for a short visit to Barranquilla, Colombia but she had to get back to teaching so I continued east on my own. It was 1972 and I had been measuring out my life in workweeks over a Selectric typewriter at the University of Washington in Seattle wondering if boredom was a permanent condition. I biked home one evening to find a letter from Terry, a high school friend. She and her husband were in Colon, Panama where he was stationed as a doc doing medical service. She invited me to join her in exploring the country. Money and time were the only barriers unless I cashed out my retirement account and quit. At twenty-six, pension planning loomed so far away in the future as to seem fantasy. When I announced my decision to do that to family at Sunday dinner, silence engulfed the table. My father reacted typically: “You’re out of your mind. You lack basic common sense. What will you live on when you get back? And when you retire? Have you any idea how much it costs to live?” He lit a Tareyton and inhaled deeply. His doctor had suggested he should cut back on tobacco if he wanted to see retirement age. My mom’s lips tightened, but she just shook her head. While both applauded travel, they insisted one needed to plan and budget for such extravagance, not just jump on a plane, but Terry and her husband would be long gone by then. Ignoring parental concerns, I quit my job, gave up my apartment, rehomed my two gray cats, and cashed out my retirement. After a six-week course in Spanish that fall in Mexico City, I flew to Panama.

I’d always jumped into whatever new adventure was presented. Like the five-day hike into alpine wilderness or skiing the intermediate hill as a beginner until I fell and dislocated a hip. Or learning to sail by casting off in a sailing pram without instruction. Daddy was instrumental in that nautical fiasco. If I stopped and thought about the repercussions of giving up work, I’d never get anywhere. Finding work had never been that difficult. Maybe I was cocky, but I saw it as adventurous.

Coro was a charming spot, but quiet for a port town, and I did not want quiet. I wanted adventure. I wanted to meet Caribbean people, listen to music and eat croquettes and golden oliebollen (dumplings), swim, scuba dive. At the marina, a captain agreed to ferry me across the sea for a bargain thirty dollars. We were destined for Curaçao, which, along with Aruba and Bonaire, make up the ABC Islands of the Lesser Antilles. Descriptions of this island settlement of houses with Dutch doors in bright colors were enchanting, different from anything I knew.

Coro, Venezuela is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a port town of about 200,000 founded in 1527 as Neu Augsburg by German explorers. The town’s churches, domestic, and civic buildings employed traditional mud-building techniques including bahareque (a system using mud, timber, and bamboo), adobe and tapia (rammed earth) still in use today. Ubiquitous are the Spanish Mudejar architectural components like the horseshoe arch and vault, painted in earthy umber, brown and ocher with tile roofs. The word comes from Arabic mudajjan “permitted to remain” referring to Muslims who stayed in Spain after the Reconquista.

Local tradition traces the town’s name from the local Caquetio word curiana, meaning “place of winds.” Had I heeded that name derivation, I would have caught an airplane to visit the island instead of a boat. Sleepless much of the night, I had no trouble getting down to the boat early and boarded the Bienvenidos, a forty-foot white round-bottomed boat for the short (three plus hours) trip to Willemstad. The captain and his eight crew members cast off, and we got underway.

Proud of my self-reliance, I was excited to set out on this escapade, my first solo challenge as a vagabond, and joked with the crew members in my beginning Spanish about my vast boating background growing up cruising the inland waters of Puget Sound. Although the Caribbean is known for smooth sailing, it can get choppy in areas where it meets up with the Atlantic Ocean. Neighboring land masses provide little of the protection found in Pacific Northwest water. Like my explorations, clashes could occur at a moment’s notice and those moderate waves grew to towers crowned with foaming whitecaps. Now, the slightest roll of the boat had me clinging to a tin bucket, non-stop puking and despair. Had I spewed up my adventurous spirit? Had my zest for living brought me too close to the brink? Nobody forced me onto this boat.

Crew members clung to anything they could grab, and I careened into the cabin. I cannot be sick, I thought, aiming for the head. Me, an old salt, raised on boats in Puget Sound, behaving like a green newbie. Years of experience, indeed.

“Please put on this life jacket,” the captain said. “I think fresh air will help but we’ll have to secure you in the cockpit or you’ll fly out of the boat.”

The crew agreed I should stay outside, probably because I kept throwing up, but I could not stay balanced on the cockpit’s narrow side bench; in spasms, I rolled off the seat. They tied me to the bench through the straps of my orange life jacket like the one I wore as a child, while dry heaves wrenched my depleted body. The sea was a furious green roiling mass and I feared we would never reach port. And if we did, you can be damn sure I’d fly back to Venezuela.

Like a wounded creature, the old boat’s engine labored while the men ran back and forth, securing charts, cups, and caps. Would we stall and break into pieces? Capsize?

I felt the green color of the water in my stomach as I hopelessly struggled not to throw up again. Seasickness is so debilitating one loses any sense of self and just wants to die or pass out. My eyes were heavy, too, as I aimed for the bucket beside me. The only thought which kept me going was that if we got to the island, I would use the “for emergency only” credit card and buy an airline ticket for the next leg of my journey. Would this ever end? I never wanted to get in a boat again.

Terry had made this trip to the ABC islands months ago and I hoped to keep up with her adventurous spirit and enthusiasm. Doubts edged in when I thought about anything else other than how sick I was. Maybe I wasn’t tough enough for this economy travel. My mom didn’t call me “Madame Queen” for nothing. She joked about my prima donna ways. The physical distress had me in doubt and part of me wondered if my parents were right. Terry was a lifelong Girl Scout better versed in the hardships of roughing it, and it didn’t get much rougher than this journey. I don’t think I’ve been that sick since appendicitis. I used to joke that having had my appendix out, I was fit for transoceanic boat trips. Not true.

I looked up the timing for such a sea cruise: it should have been about eight hours, not the three times that which I endured. And I also find an NPR piece from June 21, 2019 headlined “Venezuelans Take Risky Voyage To Curaçao To Flee Crisis.” Two boats had been lost with sixty missing passengers and another boat sunk sending over thirty to a watery grave. Because of their collapsing economy, millions of Venezuelans have emigrated in recent years and Curaçao remains a popular destination even though people keep dying in trying to get there. The island used to be a trading partner of Venezuela, but borders have been closed over political controversy over the latter’s government.

At last, the sea calmed to a brisk chop. I saw stars puncturing the sky as we chugged into Willemstad’s quiet harbor and cleared customs. Looking at the hillside with its pink, mint, and yellow cottages framed by verdant foliage and bright flowers in the moonlight, I was thankful to have arrived. At least, I could find an airplane to take me back to Venezuela.

When we tied up to the dock, frail but ecstatic to touch solid ground, I asked the captain of the boat for my passport. He tipped his cap of soft, dark navy—decorated in daffodil yellows, royal blues, crimson reds — the colors of the Venezuelan flag.

“Sorry, Senorita, I am required by law to hold onto your passport until we leave the island.”

“Leave with you? By sea? I have to get back on that boat? I intended to fly to Caracas.”

“No, I’m sorry,” he apologized, “the way in is the way out,” a Curaçao law to discourage scofflaws. Your incoming mode of arrival was the departing conveyance. In other words, I could not sail in and fly out. I had to return by boat, according to their incomprehensible rules. I leaned on a cleat, wiped away tears, and lost any impetus to find a hotel or forge on as the brave traveler. My great escapade had become a trial. He took pity on me and suggested I could spend the night with his island relatives.

His family treated me well, but they could not help with the exit problem, plus they spoke no English or Spanish. They spoke Papiamento an island dialect made up of Dutch, English, Spanish, French and a few indigenous languages, the name papia, from Portuguese and Cape Verdean Creole papear (“to chat, say, speak, talk”). Despite a familiar word or two, I rarely comprehended anything said to me. Sign language helped. As did the handsome nephew, who took me dancing. He was tall, well-built, and probably five or six years younger than me. His was not the dancing I learned at PTA affairs. He held me so close I could not see at my feet, let alone think about what steps to follow as the gyrating Caribbean beat played on for hours until we were sweaty and exhilarated, and I danced with abandon. Would his aunt miss me if I did not get back? But he behaved like a gentleman in spite of his sexy performance on the dance floor and he squired me through the dusty streets, showing off his home.

Like the composite language, the island presented a striking mix: Dutch doors, pale pink, yellow, and blue clapboard houses, and the islanders of African heritage and musical language, fishing, strolling, and working in the sunshine. I tried again to get officialdom to permit me to fly out, but rules were rules. I had to return on the boat. Those were the rules. After a few days of playing tourist, I located the Bienvenidos and boarded with reluctance, hailed warmly by the crew.

Rough green seas marked the return trip, too, but it was not as bad as the journey out. Or I was getting accustomed to it. This time, crew secured me and my tin bucket to an inside bunk in the bow and I transited without a death wish, almost as seasick as earlier. After sailing for a few hours, the winds waned, and the sea calmed. Seeing the lights of Coro through the porthole settled my stomach and erased my fears. Almost back to port, my ego resurfaced. Now a seasoned traveler, I had survived in one piece, I was alive, and I started to plan my next junket to Caracas after thanking the crew.

The boat slowed down. I sensed bumps alongside. The waves had lessened but what were the bumps? Had we reached Coro? I heard loud whispers and felt a rocking motion as though something or someone came aboard. Was it Customs? Did they offload cargo? Not pirates, I hoped. Nothing was visible from my porthole except the pitch-dark sea and distant lights. To my relief, we soon revved up the engine and continued into the pier at Coro.

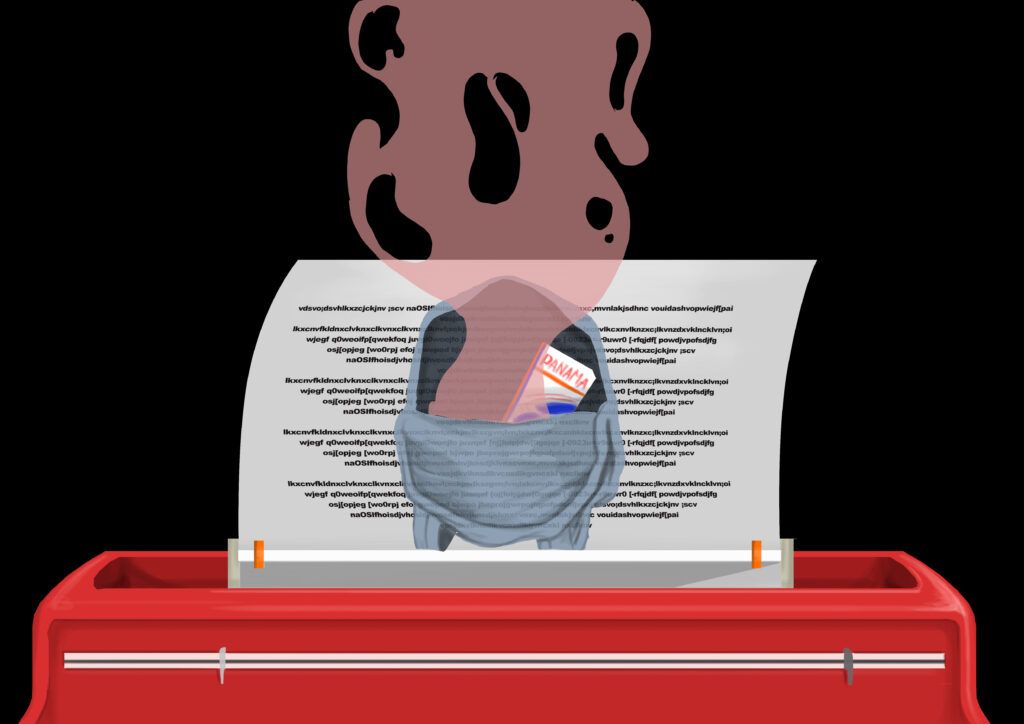

Relieved to be done with this trip, I felt grateful no one was meeting me. Imagine my family seeing me stagger off the boat of men to present my passport. The captain walked me up to the office for customs and disappeared. The inevitable official queried me about what I was doing aboard, where had we been, what did we bring back? They searched my backpack but found nothing but a red round of Edam cheese. His Spanish was challenging to my ears, that rapid coastal dialect where the speaker seemed to swallow word endings, and I didn’t understand some of his questions. I did not know why he took me into an office with a desk and a couple of filing cabinets while he held my passport in his hand. Eventually, he led me out of that office into a gray cement room with a brown canvas cot and a barred window, maybe a holding cell for the Customs Office. From what I understood, they suspected me of being in collusion with the crew who were importing contrabando. What contraband? I’d seen nothing. And I had seen no one from the boat since my interrogation began. I was innocent. How dare they lock me up? Firing squads were the fiction of magical realism, like being consumed by ants or splinters of time, weren’t they? Oddly, I was curious but not that concerned. My optimistic outlook refused to accept that I, an American tourist, would end up in a South American jail, having never smuggled as much as a bottle of rum or carton of cigarettes. What were they after? And where was my passport? The nightmare of the trip was the rough sea. The sickening crossing and that I had survived. Now, officials were causing me trouble. Of course, I would resolve it. Where did this confidence come from? The invincibility of youth, I suppose.

To wait, I sat at the table and nibbled fried plantains after which I napped on the cot. A friendly translator appeared in the morning, and I relaxed. We convinced my jailer that I knew nothing of smuggling activities by the captain or the crew. The translator told me they were looking for contraband, not drugs, i.e., transistor radios and cameras and microwaves. Perhaps they detained me in the hopes of a mordida or bribe, but I did not grasp the need to fork over cash.

He told me two boats did not return after the storm. We were lucky. No sign of the amiable captain again.

Once the Customs Officer let me go, I hurried to catch the bus south to Caracas. I felt sure that the worst was behind me. I was back on a balanced keel.