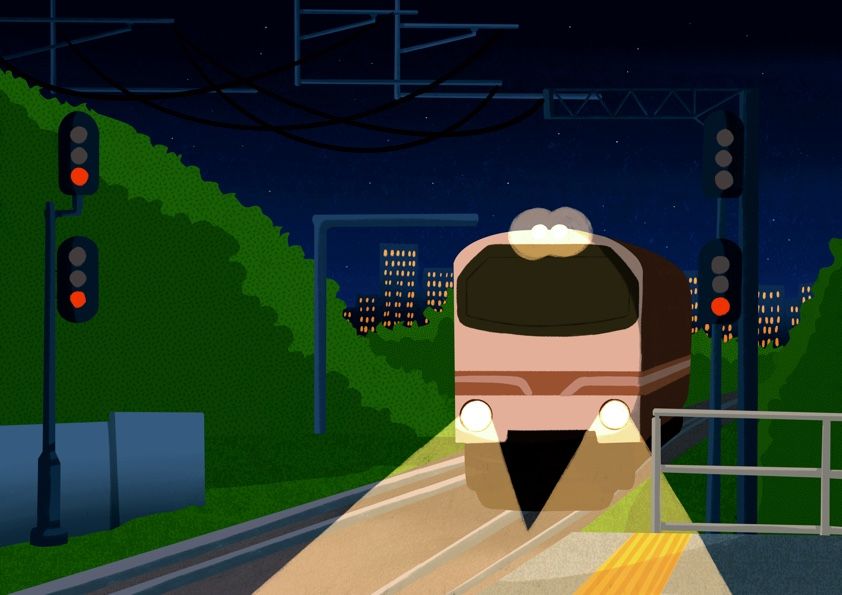

On the night that Charlie Mason died I watched a freight train slow almost to a stop, then speed off again into the darkness.

I would not have attended Babylon College if it were not for the many trains which trundled through campus throughout the day. The train track, which cut its way like a scar just beyond the main quad, had had been the deciding factor that sent me to Babylon for four years.

It was silly, I suppose. But after a dozen university visits, a dozen fields lined with ivied buildings, a dozen speeches from erudite faculty, a dozen brochures plastered with smiling students and identical statistics clogging the mailbox weekly, I longed for any oasis of uniqueness to save me from the desert of liberal arts colleges. And then came Babylon College, and its train tracks. And there went I.

On the night that Charlie Mason died, I sat across from him at dinner and regretted all the sympathy I had ever felt for him. We were roommates, flung together by random draw, and from our first handshake I knew we would not be friends. He had the insecure businessman’s handshake that preferred to vanquish its new acquaintance rather than greet it. That handshake taught me Charlie Mason was either a too-ambitious econ major, or a jock who didn’t know his own strength. When he mentioned he played football, I decided the second option was true. When we ate that night, I learned that neither was.

On the night that Charlie Mason died I saw him sitting on a bench in the shadow of the student union, alone. When I saw him, I felt pity for him, and my pity sealed his fate.

“Hey,” I said, “You hungry?”

He nodded.

“I’ll eat with you.”

Another nod. “Okay. But not the cafeteria.”

I did not need to ask why he wanted to avoid the cafeteria. I had seen the glares of our fellow students that followed him around like his own shadow. We set off to a student-run diner.

On the night that Charlie Mason died, I learned the diner had a reputation. It had so far survived four or five attempts by the administration to shut it down for failure to card minors who ordered alcohol. Located on the edge of campus across the tracks in the basement of the college’s oldest building, it took inspiration from the seedy bars of detective novels. Narrow windows and dim lights completed it speakeasy aura.

On the night that Charlie Mason died he spoke more words in a row to me than he ever had before.

“It’s not fair,” he said through a mouthful of pork sandwich. “The investigation was supposed to be private. They told me so. Then the whole thing gets plastered on the front page of the school paper.”

A swig of his glass. He had beer. I had tried whiskey, and was regretting it.

“That girl Amy probably went to the paper. Then they printed it right up, one-sided and nothing but lies.

“Coach kicked me off the team too. I’m their best punter. They’ll regret it soon enough—that offence sucks. They’ll punt lots, and Johnson is nowhere near as good a punter as I am.”

I listened to him rant. I learned he was a chemistry major. I learned Babylon College had been his third choice of schools. I learned he had been drunk on a certain Saturday night last month, the night I was forced to sleep in the library, because he hadn’t been alone in bed.

“They say she was drunk, but so was I, so it doesn’t count, right?” He said, and that’s when I remembered I hated him. I had hated him since that night, first for exiling me, then later for what I read in the school paper. My hate had turned to sympathy when I saw how everyone else hated him too, but when I saw he had no remorse or guilt or repentance, I hated him again.

“Shut up,” I said. “Just shut up.”

And he did. We never spoke another word to each other. I finished my sandwich, and my drink. He finished his sandwich and kept ordering more drinks.

On the night that Charlie Mason died, I slept in that same room in the library I had the month before. His ghost slept with me, and every night since.

On the night that Charlie Mason died, we stumbled out of The Pig at the latest possible hour. I let him walk in front of me, planning to slip away once we were closer to the dorm. But he stopped on the train tracks, hand to his head, legs wobbling. I stood behind and glared at him like any other student would.

When the light first shone in the distance, I said nothing, because I assumed Charlie would notice. Then it came closer, and I was still silent, because my hate had consumed not just my sympathy, but even my human decency.

There was no horn. They never blow it at night, so they don’t disturb sleeping students. Charlie, drunk as he was, might as well have been asleep. I didn’t rouse him.

I closed my eyes, but forgot to stop my ears. First the screech of brakes. Then a thud. Just a thud, like a bag of flour being dropped on the ground. I could still hear it despite the sound of the braking train. Then the sounds stopped, and I looked again and saw the train speeding up until it faded into the night. Perhaps the conductor had convinced himself it had been an animal, or hoped he could run away from the problem. Perhaps I had convinced myself he was an animal, too. And once the train had gone, I also ran away from the problem.

On the night that Charlie Mason died, I fled from the scene as fast as I could. They labeled it an accident, and I never told anyone otherwise. But I know that I murdered him. His ghost reminds me every night when I try to sleep. I don’t believe in ghosts. But I believe in Charlie Mason, and I know he will haunt me forever.