The wind passed through the village of Damoford. The once common sound of animals had fallen silent, a lonely bell letting out an empty clang in protest of their absence. Rain pattered against the roofs softly, or were sucked into the earth, the mud left bereft of boots squelching and disfiguring their fluid state. For a traveler passing through, instead of finding homes lit with the dim illumination of a secluded candle, they would have found naught but embers and ashy remains. All the buildings were empty of light. A serene, empty darkness that swallowed all within its overpowering grasp.

All of Damoford was gone, bar the tavern. There, one last light showed out into the dark. The sound of soft, forlorn words crept from the plaster and wood building. Pitiful, yes, but a beacon all the same to travelers in the night.

“Another two gone today.”

Low murmurs rose up in the tavern. Maybe a decade ago, they would have been shouts, or shrill screams of terror from those folk tender-hearted at the thought of a disappearance. But 10 years on after the malignance had been first sighted spreading across the land, the horror stories spoken by those who fled it brought with them, and the people of Damoford had grown woefully accustomed to what approached them. Instead, only tired eyes and thinned scowls were the predominant reply.

Ashban swirled his mead in the flagon he drank from. A somewhat thin man, with drooping eyes and a scraggly face that hadn’t seen a razor in far too long, he asked what was on everyone’s mind. “Who was it now?”

A woman he was unfamiliar with answered after more than a moment passed. “Bea.” She whispered through chapped lips. “She’s been taken for more than three days now. Her clothes are with her father and mother. She’ll not return.”

“Alderman’s daughter?!”

“No!”

“Can’t be.”

“It’s the truth.”

“Blackened’ fog.”

The inn’s occupants offered up their own ideas as to the thought of their village headman’s loss. The thought of which was almost anathema, for he was the most zealous of them all in his protection and watching of his family. Incense, torches at night, watches: none were off the table for Tetson in a bid to protect his family and safeguard against the encroaching mists. No one in the inn doubted the man would be out, sooner than later, trying to find his lost daughter. No one doubted that he too, should he stray too far, also would be swallowed by the mists.

Ashban drank his mead again. Setting it aside, he asked the other question. “And the other one?”

“Demevend.”

Then that explained it. When the lonely shepherd had stopped in Damoford in his rare interactions with its people, he’d seen the blossoming romance between the Alderman’s daughter and the wood carver’s son. It was as heartwarming as it was tragic, as every inch closer the mists came to Damoford. Their loss would be another burden for the people to bear as the malignance threatened to overcome the whole of the world.

No one knew where the malignance originated from. No one knew why the thing even existed. Some seemed to believe that it was brought about by man’s unfaithfulness to the life-sustaining flame who created man to flourish about and watch over the world. The malignance was therefore their punishment for their children who’d spoiled the world with their depravity. Or it was the anathema: the opposite of the flame. Others claimed that the malignance was a creation of the eastern civilizations, gone wild by a fluke and now consuming the world.

To the village, Its first sightings for certain were at the Thresher mountains, which was the furthest-most-east the people of Damoford had ever seen on a map when cartographers happened across their town. From there, the malignance spread across the great plain which dominated their lands. The last runners to come through Damoford spoke of the mists being only a month away from the town.

That was 4 weeks ago. Ashban was certain that they’d have a week before the mists came. At best. Once the mists were there, they’d have their way with whomever remained in Damoford. And after that…he did not know. No one had survived to his knowledge. Not the great cities beyond the yellowed river-a half a week’s walk from Damoford-where the learned across the known world came to ply their trade, nor the grassy steppe where the horse lords found tribute astride magnificent stallions. Naught but silence was the answer, and the flight of those who could outpace the fogs.

Damoford would be gone too. There was no stopping it. His wandering with the flock saw him travel across the countryside, and one time did he come within viewing distance of the fog.

Mead splashed on his hand. Curious, he looked down, beholding a shaking set of hands. Even now, his mind whispered. Even now, you can feel it. Death, that walks on the earth. Ashban cursed at his thoughts, and stilled his hands.

He peered out to the rest of the tavern. The faces that stared back were older than would normally be there. The Dancing Ferret ought to have been filled with fresher faces, with drunken rabble-rousers carousing about the tables. There should have been fights between hot-blooded farmers, stopped only by the intrusion of an irate forgemaster putting to an end the tomfoolery. In his younger years, in the rare times he took to not tending his flock, he welcomed such entertainment and distractions from the tedious and lonesome work of guarding sheep. Silence, now, was the replacement. Older folk, too unwilling to leave as the end approached, were now the only company he could content himself with these last few days.

The small gathering of people in The Dancing Ferret were all that were left of Damoford now. All of the young people had fled, seeking refuge in the cities west of their ancestral homes. A few, he heard one time, remarked that they could find true safety across the water on the isles of Sorcosa in the south, or in the great island of Deved to the west. Ashban doubted they would find it there, or anywhere, but a part of him almost wanted to go with them. Why didn’t he? The thoughts turned on endlessly. All he could make out was that they were damned.

There was a knock at the door. All eyes that could still see turned to it, confused. They were all that was left. Surely, it could not have been someone new? Who in the name of the almighty could have come here, on the edge of the world of man? At first, they reasoned it was merely the wind, buffeting the knocker. None rose to meet the knock. Another dull, rapping noise sounded out across the tavern. People looked about each other uneasily: there was no mistaking it. That was deliberately knocked.

Ashban stood up. He possessed an unfamiliar energy about him, almost invigorated by the knowledge that a new person was at their little gathering, but also felt frightened as well. He couldn’t say how, or why, only that it was everywhere, from his hair tips to the marrow in his bones.

“I’ll…get the door,” he remarked. No one spoke anything as he rose from his seat, but he could feel all of their eyes on him as he lifted the plank of wood they’d put down to crudely lock the inward-opening door. He tentatively brushed his hand against the door…and missed. He blinked, and stared at his hand as if it were some foreign object.

What am I doing? His face hardened, but his eyes remained hesitant. It’s a simple knock. Open the bloody door.

No it wasn’t. Ashban’s mind told him that there was most likely one last, unlucky traveler. Harmless, if they were so close that the mists nipped at the feet’s soles. His soul urged to his mind that there was no place for logic right now. That door could not be opened, under any circumstances, no matter what else was logically possible.

Slowly, his hands shaking under his will’s command, Ashban lifted the plank from the door. Total silence had filled the tavern, and the dull sound of the old wood falling to the stained and dirty planked floor reverberated in the space, louder than it ought to have been. Hands raised again, he pushed against the door.

Bearded. That was the first word that Ashban conjured in his mind upon meeting the stranger. His hair was coarser, colored in a deep, dark black that contrasted with a faintly tanned complexion. The flesh of youthfulness was still on his face, but strong bushy eyebrows set in a perpetually aggressive glare. The rest of his apparel was equally odd. A brown-colored wool cloak clothed his head with a hood. A short cream-colored gown to midthigh was his undershirt, and above that a patterned leather vest with many pockets that Ashban was certain were full of unknowable things. His pants were battered and dirtied, slightly loose around his form. Two long boots held together by grime, leather and hope, wrapped around his legs. The apparel was, in a word, contradictory.

Ashban looked perplexed, but immediately felt the strange man’s eyes upon him. They were focused eyes that bored into him, dark brow, betraying a determination that Ashband had not often seen on the faces of the young. He gulped instinctually, and forgot to say a word of greetings.

“May I enter?”

Ashban blinked, surprised that the man could speak his language as well as he did, the accent slipping in slightly. “What?” he gargled, his tongue leaden, and unable to say more than a single word.

“May I enter?” The way the stranger said it, implied the importance of answering in affirmation…and brooked for no dissenting opinion. Ashban said nothing, and opened the door, standing aside for the traveler to invade the small refuge. As he passed the shepard, Ashband heard the sound of muted baubles shaking about the man’s form, uncertain of what they were, but certain that they were not the sort of thing men so easily wore as shoes.

The stranger sat down at an empty chair, and lifted up his hood, revealing oily hair that hadn’t seen a razor or vegetable soap in too long a time. His eyes swiveled, hawkish around the room, before landing on Tendra the aged tavern owner and motioned in the air. “Beer,” he remarked simply.

She nodded slowly, complying with the order. The barrel of beer they’d all been drinking from was nearly empty now, so she uncorked another, the sudsy liquid pouring out and filling the flagon. A scant few steps was all it took but each felt measured and the time of the individual thud of her feet on the floor–an eternity to the watchful shepherd. The stranger nodded thinly, and drank deeply of the beer, his gulps resounding out as he drank the first draft. He drew breath, then drank deeply again, surely downing most of the flagon’s contents by now.

“Sir–” The stranger interrupted the thought Tendra began to ask, holding out a hand with a finger raised. He continued to drink his fill, concluding by slamming down the flagon. He drew in a deep breath through his nostrils, exhaling.

“No doubt,” he started, “You wonder why I am here.”

The tavern watched on silently.

“It’s because I have an offer for you.”

“An offer?” Ashban blinked. That was highly unusual. The man didn’t strike him as a bandit seeking to offer protection. The chill aside, he carried no obvious weapons with him.

“It’s a worthwhile offer. One that concerns the blight facing us.”

“The Malignance?” The sole youthful one in the room nodded.

“The very same. I am a scholar, you see. Not from these lands, but of the center of our world, in the learned homes of the divinely inclined. The Malignance came for us years ago as we are closer to its source, but we’d known for a long time our fate and prepared accordingly. Scant few from the great cities of the east’s scholars had come to us, but enough to know of the mist. Thus we were long gone by the time the mists had touched our walls, having fled to the westernmost corners of our world. We reside now upon the great isles of the north, our refuge…for now.”

He took another drink, shallower this time.

“We know, or rather, suspect that the mists will not stop at the water.” Ashban’s heart sank. Why? He wondered. Hadn’t it already been known? That if they’d been able to stem the fog, they’d have done so already.

“Thus, my brothers have tirelessly studied into this matter. We, humanity, must conquer this changing world as we once did when the creator set us upon it, or be damned to oblivion. Needless, our task has not been thankless, or easy. Our efforts have borne us mostly failure, while the doom has pushed us to work ever harder, push to every line” he hesitated. “–nay–gobeyond every line we thought possible.” The scholar paused, his face twisting from suppressed memories. A lesser man would have broken. He did not, yet Ashban saw for once, how tired the figure must have been. Not merely physically, but morally exhausted. He didn’t want to think about what the young man had been forced to do. Not now.

The scholar rubbed at his face. “I’ve come to you now because we believe we have found…something. A stopgap, or perhaps the end to this madness. Your village is the closest on the maps I could find to where the mists come. Only here, I think, could I be able to test what my masters have uncovered.” He looked up from his cup, latching his eyes upon the room’s inhabitants. “Will you help me?”

Silence.

It was depressingly little information to go off of, even if it was the longest monologue that the remaining people had heard in some time. The room, if even possible, had grown even more empty of noise. The rain, which had been pattering against the thatched roof, now stilled. The flames had licked hungrily at candles that borne them, reduced to paltry tongues that wavered. But beyond that, the shepard heard no movement from the rest of his kin. A voice called out. “Put it to a vote then.”

“Tetson ought to call one,” a dissenter said.

“Tetson is gone.” Ashban was surprised to hear it was his own voice that was speaking now. It was heavier, hoarser than normal. He hadn’t expected the investment in the community, either. But he spoke with conviction as he continued addressing the room. “The man lost his daughter, and with it, his will to live. We can’t count on him anymore. We need to look after ourselves. I say we put it to a vote too.”

The remaining people of Damoford looked at each other, hoping to find some wisdom in their friend’s face. Instead, all the found were mirrors of their own forlorn visage, reflecting the same uncertainty. “What will it involve?” Tendra asked. Her voice had a small edge of trembling.

The scholar looked out from beyond the flagon of beer, then reached into the depths of his cloak. Plumbing the fabric, he produced…a lantern. It was made of black iron, with fogged glass panes in a hexagonal matter, and iron bars between them. Its top was detailed, arched, and ribbed, the designs not unfamiliar on a golden lantern, but on the dull and chilling metal, it transformed from admirable to intimidating and threatening. It swallowed the light, and the foggy panes made certain to conceal whatever secrets lay obscured behind them.

It had been hooked to the scholar by a chain, and he removed the locking mechanism before placing the thing on the table, all watching it, and corrupted by the sense of foreboding it introduced.

“This is the product of our research,” the scholar explained. “Come morning, I shall conduct the ritual. This lamp will protect us, but requires a–” he hesitated, and looked aside. He downed the last of his beer and continued on, mastering his fear. “It requires a sacrifice. In blood.”

Ashban’s lips moved, but the words came from another. “It needs our deaths?” The scholar shook his head.

“No,” he remarked. “No, I believe that we will only need a portion of blood from you. Not nearly enough to kill you, but it may bring you to close to fainting. But I must have your permission. I–I shant force you to do this.” He tried to drink from his flagon, but the nonexistent beer did nothing to sake his thirst, and he slammed the wood down hard on the table. He sighed, and put his face in his hands for a second. Breathed out, and peered at something in the corner only could see, lost in his own thoughts. He’s holding something back. And every person in The Dancing Ferret knew it. But there was little that could be done. Glum faces observed the lantern.

“All in favour?”

Fifteen souls raised their hands.

“Against?”

Ten raised their hands. So it was decided.

Ashban had not answered either way. He cursed himself for the unmistakable display of cowardice. None in the inn commented on his act or lack thereof, but as they shuffled off into their homes for sleep, his mind created enough venomous insults to serve as consequences for his lack of action.

The next day came and went. The mists could finally be seen on the furthest of horizons. It has betrayed the best predictions, and was fast approaching quicker than expected. No one met in the tavern that night.

The next day saw the remaining villagers enter the main square. It was less a properly-built square, and not even very square-shaped, but more a place where the earth had been so heavily trod that grass could no longer grow, so people simply met there when they needed to. In happier times the Alderman might have hosted a passing troubadour or trobairitz, and listened as the bards entertained the villagers with poems of storied heroes, or romantic trysts between lovers. A pity that its use had been relegated to a foreigner scraping an eight-pointed star-cross in the ground. Ashban watched him as he went about his duties, digging with a small shovel. At each point of the star, he placed a thin metallic platter, the middle peppered with holes. Strange, the shepard wondered, but he kept his words to himself. No matter how profane the star looked.

At the center of the star, the scholar placed down his lantern. When he opened it, he revealed a silvery, wax-made candle unlit at the center. He brushed his hands against the cylindrical wax. Ashban glimpsed a tremor in his form as he did so.

“Scholar?” The man seemed transfixed on the candle. Ashband called out again. “Scholar?”

That appeared to shake him from the stupor, and his trembling ceased. “Are you ready,” the shepard said. He wondered at that moment who those words were meant for. He hoped that it was for the man in front of him, and not the reflection in the pool of water next to his wool-clothed form.

The scholar nodded. Crouching, Ashband could not see everything, but he did hear the sound of flint striking steel, and procured a brief glimpse of a flame sprouting on the waxy core. “Everyone, come close,” the scholar spoke, voice loud, and carrying across the open space. “We begin this expereiment…now” His gaze swept and landed on each of the people left in Damoford. It landed on Ashban last. A sun-scorched finger pointed to the shepherd, and as if on command, his stomach dropped. “You,” the scholar announced. “Come to the closest point of the star, and stretch forth your hand.”

Ashban hesitantly did as he was bade. The scholar thudded forth, boots squelching in the mud, but also infused with a hesitancy, and careful not to disturb the markings. Once before Ashban, he gripped the shepherd’s arm. “Please,” he whispered. His voice carried little of the authority from before. “Forgive me for the pain.”

He drew forth a small straight knife from his robes. A flash of metal, a sudden biting pain, and Ashban watched as blood began to drip from the palm of his hand into the cup. He immediately jerked back, but the scholar’s grip was firm, and he held fast as life essence left his body. In fact, the longer that the blood dripped, Ashban was certain that it flowed ever faster.

How did one describe the sensation? It was like a cup being drained. Like…emptying oneself. But no relief could be found in this drawing of liquid. In its place, he felt empty. A cold settling within his veins, or was it his veins became the cold itself, and did not merely carry it? His breaths felt shallow, like no matter how much air he brought in, it could not match the newly yawning hole in him. It was wrong. His arm felt sluggish. He wanted to move, jerked his arm, but he had wanted his whole arm. Why didn’t he move his whole arm? Why? Ssto stoP stopp Stoop stopstopstop–

Then the scholar was bandaging his hand, and it was over. He staggered back, face white, and staring, animal-like. He still felt the emptiness, and the loss of blood was making him feel faint. “What did you do?” He garbled. “Scholar! What did you do?”

The Scholar looked at the lamp. Ashband couldn’t have cared about the damn lamp, he wanted to punch the man squarely in his jaw for that feeling, higher powers be damned. But he staggered forward, lost his balance, and fell to the mud. The wound on his hand opened again, the bandage soaking in blood and liquified earth. Groaning, the shepard groped about in the earth for purchase, before slowing, and stopping as a red light swallowed his attention. He was forced to gaze at the terrible thing.

The lantern glowed now. Unmistakably so. The light was not so bright that it could not obscure much of anything, and the black metal that caged the light smothered any light that sought to illuminate it. Caged was the right word to describe what Ashban looked at as the light seemed to ebb, and strengthen, almost as if it were alive.

But that can’t be right? Could it?

“It worked,” the scholar murmured to his right, voice thick with an unknowable tenor. Turning, the man stuck his hand before Ashban, and peering up from the earth, the shepherd could view the face of the Scholar. His face was hard pressed, but the expression unreadable, his thoughts impermeable.

At the very least, it seemed like the man was less pensive. Perhaps it had been like plunging off a cliff into the sea: once you did the first jump, every other one was much easier to follow. At any rate, the man seemed to be less immediately frightened by what had happened than the shepard as compared to what he used to have been. Ashban was uncertain if that was disheartening, or inspiring, but took the man’s hand regardless.

“How are you feeling?” the scholar asked.

“I feel like I’ve been…” Ashban struggled to find the words, before landing on simply saying “empty. I feel like I’ve been drained.” His eyes narrowed. “Did you know that this’d happen?”

“I knew of the rumors.”

“Rumors?”

“They’re not important.” The scholar retorted.

“I think-”

“What matters is that you’re alive.” the scholar interrupted hurriedly. “What matters is that I can repeat this process with everyone else here, and perhaps save you all.” His eyes latched onto Ashban’s. “Unless you’re willing to give up already. There’s still much to do, and the mists are nearly here. So I must ask again: What are you prepared to do?”

They did as he bade.

Time passed. Day turned to the midafternoon, the sun casting dappled pink hues and orange planes across the oncoming fog. Ashan felt weak, but he took a small solace in knowing that no one else around him was in much better condition than he. In fact, as one of the youngest there, he probably was one of most, well, healed was not a word that he was willing to use to describe how he felt. The drained feeling was still festering, and also had led to the realization that even his emotions seemed dulled since the ritual. Strangely, he could only muster a portion of the anger his mind thought was deserved at this time.

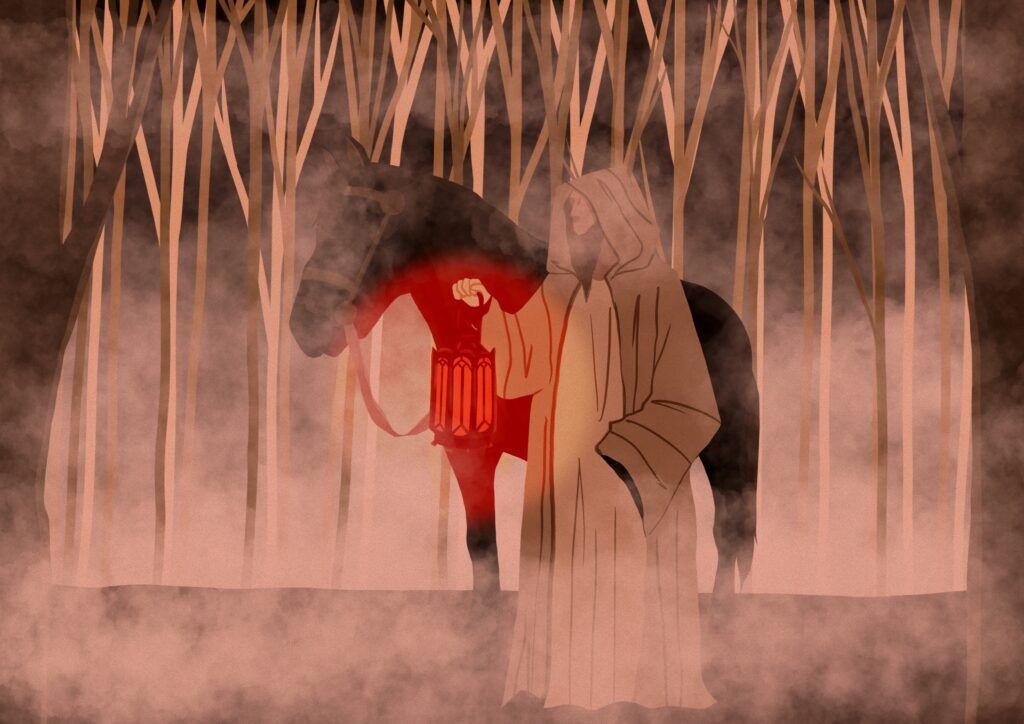

They stood together in the circle, the scholar in the middle of them. His horse was the only animal that’d been taken with them, and it rested on its side, watching the mists come closer with the rest of them. Waiting. Ashban felt a commonality with the animal. Did it understand what was coming? Did its master think to train it to not care, or was it simply too stupid to understand what was now at the edge of the village. Who could say, certainly it couldn’t be him; the man barely understood why he himself was here. The thoughts of an animal he’d never rode were lost to him utterly.

And then it was here.

It took Tendra first, for she was the one in the circle closest to the mists. She shuddered as it closed over her form, but she seemed alive, as far as Ashban could tell. Next were the two beside her, then the next, and so forth. Then the fog blanketed the scholar. Unlike those before, Ashban could still see the red light of the lantern, a beacon for all within the fog perhaps. The fog rolled over, approaching him, tendrils forming out of the mist, or were they merely products of an overexerted imagination? They stretched out all the same, real or not. Ashban grimaced as the fog caressed his beard, the follicles rustling. His arms went cold, but not as quickly as before. He breathed still, and the feeling from before wasn’t there. He was not emptied.

Had it–had it worked? He dared to hope.

No.

The chill returned with a vengeance. Suddenly, he could feel the mist inside him, entering his arm through the open wound on his body, hungrily searching for something. Just as this happened, the gurgles of the people next to him were heard. He turned, and they were slumped on the dirt. One, an old man, was spasming on the earth, but his movement had slowed immensely.

“Gells,” Ashban whispered.

Gells did not respond. His eyes grew dull, and his skin paled to an unnatural bone white. As he looked, Ashban’s own skin had begun to gray. There was no pain, but he felt lightheaded, and collapsed again. He should have raged. Screamed. Cried out in fear. He did none of these things. The world stilled, his body as well. All emotion faded from him. The pit yawned and heaved like never before, his senses dulling into–

Nothing.

There was no one left in Damoford now. No sound.

Except, for one.

Once shallow, his red lantern offered protection from the elements. His breath grew in strength while all others stilled, as if he had stolen them from the bodies that surrounded him. The scholar supposed he had. He clicked his tongue, and the horse beside him arose, it too breathing. Mounting the beast the scholar took one more look at the lantern. It blazed forth, casting his face and form into a million fractals of red and shadow.

“It works,” he said at last to himself, marveling at what had been achieved, hating himself for what had been done. The horse moved, and passed beside one of the villagers. He didn’t know their face, or name, but they’d done a greater service than he could have ever asked if truthful. He opened a case, and produced from it a most valuable commodity: paper. He began to write.

Masters,

I write to you now within the mists. The experiment was a success: sacrificing the parts of souls of people to a quicksilver candle through blood, provides the bearer of these lanterns with safe passage through the mist. I do not know if they are indefinite, and I suspect that mine will not last me very long. That is why you will receive this message by avian.

It is true. We may yet have something to face this crisis. I cannot tell you if this is a solution, for there may likely be no permeant protection from the fog. It burned through the limited souls of the villagers quickly, and though I have much of the energy of nigh twenty people, that should not be seen as indefinite. I pray, you receive this message in time, and that the bird that delivers it does not fall prey to this as well.

We may yet save Mankind. May the heavens forgive me.