“The one thing they never found a cure for was the freezing,” she said.

“Could you elaborate on that for our audience?” The interviewer asked.

“Of course. As you know, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, cryogenics was the practice of freezing someone with a serious illness or injury in the hopes that in the future, science would be able to cure their disease.”

“But that didn’t happen.”

“Well, technically it did. We’ve found a cure for all but a select few diseases whose answers elude us. But thawing out the victims, that’s another matter entirely.”

“Come now. Surely that’s a relatively simple matter in comparison?”

“The people of the past certainly thought so,” she said. “But the fact is, by freezing these people, they were effectively committing murder.”

“How so?”

“These doctors killed their patients before whatever disease they had was able to run its course. I don’t know what else you’d call it.”

“But surely these people aren’t dead?” The interviewer asked.

“They’re human popsicles, Jeff,” the scientist said. “Believe me: they’re dead.”

“Fascinating,” the interviewer said. “I’m sure our audience finds this interesting, particularly those with ancestors on ice, which is why we’ll be right back with Dr. Janet Goldman after this.”

“Cut!” The director called.

“How am I doing?” Janet asked.

“Good,” the interviewer said. “Though I think telling people it’s a lost cause is unnecessary.”

“It’s the truth.”

“You could say it a little less bluntly,” he said. “Our audience includes people with family who underwent this process.”

“Two-hundred years ago.”

“It’s still cold.”

“You want me to lie, then?” She crossed her arms. “That’s not happening.”

“No, of course not. But maybe you could, I don’t know…show a bit more optimism?”

“We’re back in ten!” The director called.

“I can’t be optimistic about death,” she said. “That isn’t who I am.”

“But that’s where you are,” he said.

“Three! Two! One!”

“And we’re back! So. Before the break, we were discussing the hope families with people who underwent cryogenic preservation have. Tell me honestly…is there any?”

“Any what?”

“Hope…?”

“Oh!” She hesitated. “I mean, over time we’ve discovered cures for most of what the patients suffered from. Who’s to say what we’ll discover tomorrow?”

“Earlier you called the patients victims. Why did you refer to them that way, if I may ask? And would you still characterize them as such?”

“I feel very strongly about the preservation of the golden rule of medicine: do no harm. Honestly, given what we know now, I see freezing these people as harmful, not only to the patients, but to their families as well.”

“How so?”

“Hope. When those who were cryogenically frozen became a topic of conversation a few years ago, a lot of families were given hope, if not to reunite with loved ones, then to meet their ancestors. As of right now, that isn’t a possibility.”

“But…it could be?”

“It was good.”

“I don’t feel good about how it ended.”

“I’m telling you it was fine.”

“I lied on national television.” She stared into her coffee, steam tingling against her eyes, but she didn’t shut them.

“You gave a few people hope.” Cathy stirred her coffee and took a sip. “People need hope.”

“I’m a doctor. I shouldn’t have done that.”

“An ironic statement.”

“Pragmatic.” Another sigh.

“All right, question. Let’s say you shouldn’t have done that. What happens?”

“Beg pardon?”

“Not to be cliché, but what could go wrong?” Janet watched her friend take another sip. The café was full, people at every table in bubbles of their own conversations. How many of them had seen the interview? Had any? Would anyone recognize her?

She sighed. “I don’t know. And I don’t think I want to.”

“Think about it, get back to me.”

“You’ve been a big help.”

“You did good, honey,” Jack said as she walked in the door.

She hugged him and gave him a kiss. “That’s what Cathy said.”

As if reading her mind, he asked “Did it ever occur to you she might be right?”

“Not really, no.”

They were in the kitchen now. Jack put the kettle on and started preparing two cups.

“None for me,” she said.

“Yeah right.” He knew her too well.

As the water began to boil, he began to speak. “You know, I don’t know if I ever told you this, but my great-grandfather underwent the procedure.”

“Excuse me?” She searched his face for signs of a joke, but there were none. Just his silhouette against the steam from the kettle.

“He got himself cryogenically frozen.”

“You never told me that!”

He shrugged. “It never came up. In any case,” he said, “Nothing you said mortally offended me, so I really wish you wouldn’t be so hard on yourself.”

She hugged him again. “Are you sure?”

“Positive.”

She stepped away. “It doesn’t change that I shouldn’t have done it.”

“Well then, maybe it’s something you could work on.”

“What do you mean?”

“Figure out how to unfreeze those people. Make something good come out of it.”

“It’s not that simple.”

“Then make it simple. If anyone can do it, you can.”

It was absolutely impossible. Dozens of scientists had worked on it over the decades, and nothing had ever come of it. All the patients who had been thawed successfully had failed to wake up. Many had extensive damage to their nervous systems to the point that if they did awaken they would be crippled.

Still, one theory had occurred to her that she couldn’t get out of her mind, and it involved what scientists of the past had been thinking when they froze these people in the first place.

The theory in the past had been that if you froze someone, eventually science would find a cure for whatever ailed you. They had been considering the freezing process as one of the things requiring a cure. In other words, they had thought they needed to cure death by exposure.

That was not the case. If her theory was correct, all that was required would be to treat the ice as an anesthetic, and slowly ween the patient off of it in a controlled environment. This was a form of hibernation; all they must do is remove the factor enforcing that hibernation, and heal any tissue damage after the fact, which was perfectly within their power. Remove the anesthetic, heal the tissue damage, and in theory, normal brain function should resume.

All scientists before her had treated the ice as a disease unto itself, but it wasn’t. It was anesthetic, and all that needed doing now was to bring them out of it.

She began putting in late nights at the office, attempting to figure out the logistics of it. A week went by where she rarely slept, so excited was she by the renewed prospects this research entailed.

It was one in the morning when a knock sounded at her office door.

“Come in,” she said absently. She was hardly aware of the man who entered. “May I help you?” She inquired, refocusing her attention with difficulty. He was elderly, likely in his eighties, loose skin and wisps of hair framing his face. It was then that she noticed the gun.

“What is this?” She demanded.

“The receptionist told me you hadn’t left yet. I informed her that I was here to issue a congratulations on your televised appearance.”

“Something tells me you’re not.”

“No. I’m not.”

“What is this about?”

“Your assertion that those who are cryogenically frozen are ‘human popsicles’.”

A sinking feeling emerged in the pit of her stomach. “I’m sorry if I offended you in any way—”

“That’s not the issue,” he said. “I want you to revive someone.”

“It’s impossible.”

“No it isn’t,” he said. “Do it.”

“Listen, since that interview I’ve been researching the subject, but I’m nowhere near an answer yet,” she said. “I literally can’t do it.”

“I think you can,” he said.

She was trapped. She couldn’t help him, she knew that much, at least not yet, and he didn’t seem like a man who had time to be patient. His hand was shaking. What did he want from her?

The man had an almost professorial aesthetic to himself. She suspected at one point he’d had quite the presence; a unique ability to hold a room and impart knowledge. Over the years that presence had crystalized, hardened and cracked. He had become rigid, unmoving, his mind often drifting to someone he couldn’t have. She found herself believing he would do anything to achieve his goal.

“What do you want me to do?”

It was his wife. The cryogenic process hadn’t stopped until approximately sixty years ago. They were newlyweds at the time. She had an incurable form of cancer. He had never moved on. She was sure he wasn’t the only one with that same story.

Still, she supposed, from his point of view, she was still alive. As long as she was frozen, he had this tiny semblance of hope. His life had been on hold; unchanging for the last sixty-two years. No lovers, no serious relationships…just friends, and his diminishing circle of family.

She’d told Jack what was happening, and he’d wanted to call the cops, but she hadn’t let him. Something about this man made her think she wasn’t in real danger, and more than that, she wanted to help him. He insisted on being present whenever she was working on his case.

“What are you doing?” He demanded as she worked.

“I’m trying to figure out how slowly she must be awoken to avoid sending her into shock,” she said.

“What does that mean?”

“That she could die again if we wake her up too quickly.”

His hand was shaking. She kept glancing at it, eyes following the twitches. He wasn’t well. He caught her staring.

“Parkinson’s,” he said.

“Is that why you’re doing this now?”

“No. Keep working.” She kept glancing at him, but did as she was told.

“I’ve learned to live with it,” he said.

“Then may I ask why you’re doing this now?”

He hesitated. “Things aren’t the way they were.”

Though he didn’t say it explicitly, she knew exactly what he meant. He wanted to see her again while he still knew her.

“Now keep working.” His hand shook while she worked.

It took her three weeks to develop a viable plan. The gun that had initially prompted her had long disappeared. Still, she felt some kind of duty to make this happen for him. His hands continuously shook.

His name was Harlan. As she got to know him, she found she had been correct about his profession – he had been a university professor. He’d never officially retired; rather, he’d gone on an extended sabbatical. His wife’s name was also Janet. Harlan said she reminded him of her.

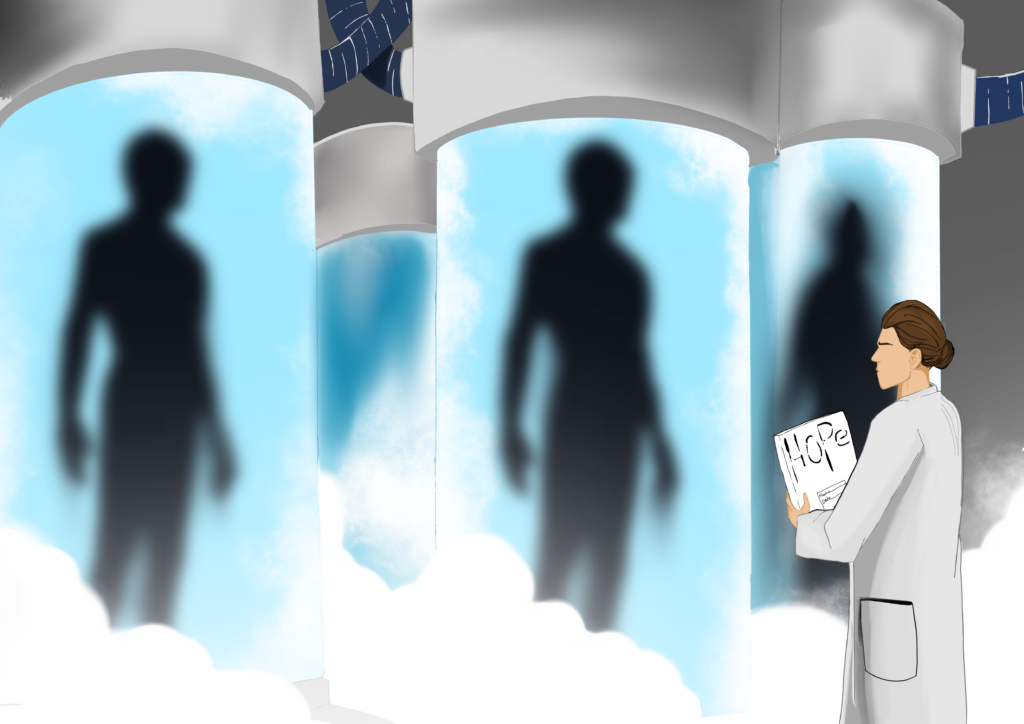

The facility Janet was in required a family member’s permission for her to enter, and an attendant to accompany them to the appropriate section. Before too long, the sterile hallways gave way to a chamber of frozen time; humanity in stasis.

“You understand, we no longer possess the facilities necessary to awaken anyone since our funding was revoked,” the attendant said. “All we have is what’s necessary to keep the lights on while the suits argue over what constitutes murder for the sixth decade running. If you want to try, she has to be transported.”

“We understand,” she said.

“Am I to understand you have a facility capable of the necessary procedure?” He seemed almost hopeful, she thought; he worked in a place of hopelessness, where human beings remained in perpetual silence, long forgotten by science. Anyone would want a light at the end of the tunnel, and she was that light for this man.

“I have connections in the medical community,” she said. “I can make it happen.”

She organized for the procedure to occur the next day, arranging for the patient to be transported to the nearest hospital. According to hospital policy, she wasn’t permitted to perform the procedure alone, not being an employee on file, but she insisted on her presence, and the administrator was happy to oblige. While she was getting set up, her client, as she had grown to think of him, stood by, watching. “Are you doing the procedure?” He asked again.

“Yes,” she said. “I am.”

“Is it gonna work?”

She kept her eyes fixated on her preparations. “I wish I knew,” she said. Her voice trembled, matching the cadence of the room.

The procedure had a fifty-fifty chance of working. She knew that going in. It was a delicate balance of temperatures, slowly increasing, healing the tissue damage as she defrosted. That was the biggest hurdle; the tissue had to be fully healed by the time the ice had totally retreated in order to prevent damage to the nervous system. It all depended on whether her theory was correct, and even then, they still had to cure what had put her there in the first place.

Thus, when the woman opened her eyes, she let out a breath she hadn’t known she’d been holding.

“Shhh,” she said, soothing her. “You’re all right.”

“Where am I?” She intuited the words from her movements; her mouth was moving, but nothing came out.

“You’re in the hospital,” she said. “Your husband’s waiting to see you.”

An attendant appeared in the doorway.

“What is it?” She asked before the attendant had a chance to speak.

“I need to speak with you outside.”

“I’m busy.”

“It’s urgent.”

She looked at the attendant, seeing the look in his eyes for the first time. She looked at the doctor across from her. The doctor nodded curtly.

“Give me a moment,” she told her patient.

“What’s so important?” She demanded as she left her patient behind.

“Her husband,” the attendant said. “He’s dead.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“He fell off the roof.”

Did he fall? Did he jump? That’s what she wanted to ask. Instead, she said “did he say anything?”

“He said he was going to see his wife.”

She was numb all over as she returned to her patient. He was dead. None of it mattered. She’d known he’d been getting worse, but she hadn’t thought it was that bad. She’d thought she could help him. She pictured Jack lying dead on the pavement, Jack’s face on an ancient body, desperate to see his wife again. The image was gone almost instantly, replaced with reality: a sick old man, dead.

In the old days, he may have been frozen. Until now, that was as much a death sentence as any other condition, but now….

The woman looked at her from the table as if asking where is my husband? She didn’t know what to say to her, so she just said “You’ll be all right. You’ll be all right.”

The words rung hollow in their sterility.