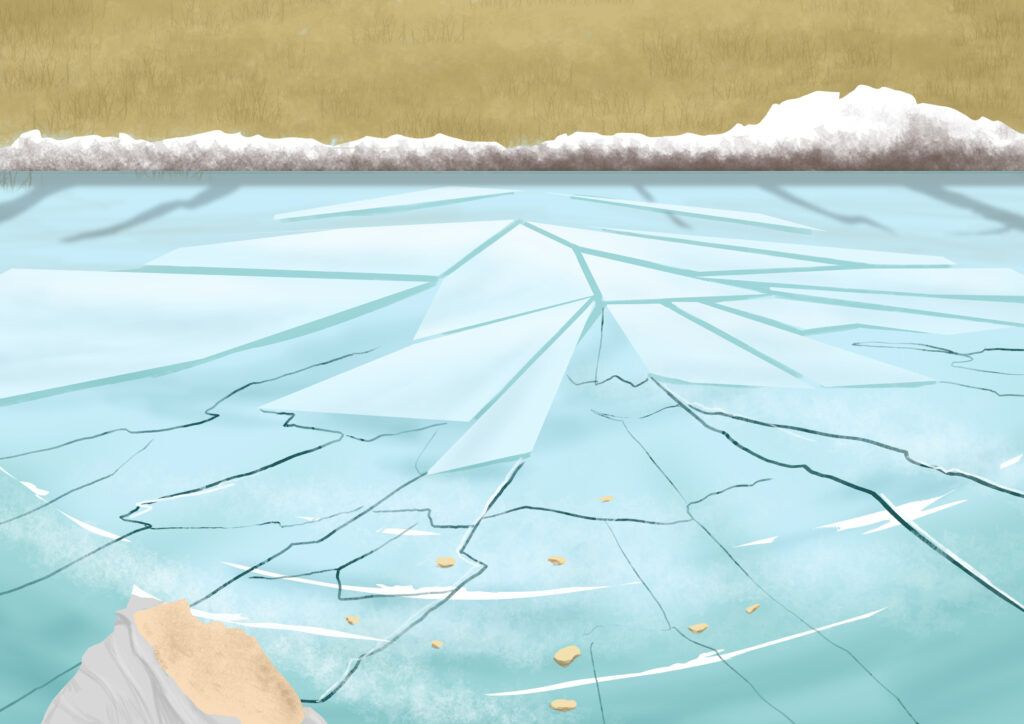

There are ice floes on the river. They are frozen there, like in a photograph. Only when I do not look at them directly do they glide by in silent grace and resignation. There comes Karen out of the night, who I had met and wed on a bright and blossoming day in May, a memory now wrapped in ice, decades old.

“Do you remember,” she says, leaning heavily on the thick, corroded metal railing at the river’s edge, “how you looked at me when we first met?”

A snow flake lands on her hand. The skin is spotted beyond her years and there is less flesh beneath the skin than should be. There was a time when I cared about such things, was horrified and panicked at every new sign of decay when we met like this. I learned that in the face of futility it is better to do less than try too much. The snow flake does not melt. If it can hold out this long, it can hold out forever, but in a single moment it collapses. I blink and it’s a drop of moisture. Karen has not even noticed.

“I remember,” say I.

There had been blossoms on the wind, sailing past the tall and narrow windows of the dining room, as if cast upon the breeze by a film crew who sought for a particularly wholesome effect. The blossoms came off the cherry trees that lined the tiered stone terrace. The weather had taken a turn toward hot summer and so the smartly dressed waiters had set out tables and chairs the day before. Blossoms covered everything, however. Drinks and dishes would be flavored with them, so everybody dined inside.

“You tried to pick up your fork from the floor,” I say, “and almost pulled the wine glass down with the table cloth.”

She laughs. It was the same soft giggle of almost secret amusement that she had issued when she realized that I had only saved her from turning a minor mistake into a big one. “I thought you were trying to make off with my glass.”

People like to hear about such moments, and it was an easy one to recount. It had a certain cuteness to it, sort of like boy saves girl, though it could just as easily have been girl saves boy. She sighs, far away, but suddenly she reaches into the pocket of her camel hair jacket and pulls out a plastic bag with the crushed and crumbled remnants of old bread. The jacket is mangy, it has bald spots and seems touched here and there by a greasy shine.

“I wanted to feed the ducks. I’m sure they’re starving.”

She pulls moldy bread out of the bag and tosses pieces of it down into the water.

The ducks have long ago sought warmer climes.

I don’t look at the pieces of bread on the water, I look at the ice floes in the distance, holding them steady with my gaze, not wanting to let them pass on. They are all sizes, some large enough for a dozen people to stand comfortably, others too small, even for a few ducks.

She says, “I can’t believe people eat ducks, can you?”

“People eat all sorts of things.”

She shakes out the bag, then drops it into the water, but she has lifted her eyes up into the dead glowing sky. “They’re still up there,” she says and wipes her fingers on the coat.

“Who?” Dutifully I peer up at the sky.

“The eyes,” she says in a hushed tone. “They’re circling, you know, always watching.”

She’s talking about police and surveillance drones. For some reason I feel compelled to play along. “I wonder if they like what they see, or if they’re bored to death.”

“They never get tired. They don’t sleep.”

“Maybe you’re right.”

“I’m always right,” she says, her tone already become distant and distracted. She pats her coat. “I wanted to feed the ducks but I didn’t bring any bread. How forgetful of me.”

“Maybe tomorrow.”

Her face lights up, but the smile does not reach the eyes. She nods as the smile slips down her face again, gone before it has peaked. “I’m really sorry, you know?”

“Sorry about what?”

“About Esther.”

This is where it gets difficult, but I know that she couldn’t help herself.

“I know,” I say. My throat is so tight it almost hurts. Any more and it would crack. Sometimes I wonder why I am doing this to myself.

“She was affected, I think I told you. Did I tell you?”

“You told me.”

“I had to get her out before it was too late, you understand that, don’t you?”

Ice floes swim in my eyes. I want to breathe but cannot. My whole body begins to ache. It never gets better, it just won’t. Vaguely I nod but try to close my ears. Memories and repetition fill in what I try to shut out.

“She’s safe now,” she says after a silence. “I talk to her every day.”

A trail of blood on the carpet and some kind of amorphous blob at the end of it, dark and reminiscent of a semi-transparent balloon covered in gore, with a curled-up doll inside, cold and lifeless by the time that the paramedics arrived. It had been hours. The truth did not come out of Karen’s mouth until almost three decades later, right here at the railing on a day when ice floes resigned themselves to what would forever stay out of reach.

“I must go,” she says. “She’s waiting for me.”

It is the first time she has ever said that. Surprised, I watch her go, a limp in her gait, a bend in her back. The mangy camel hair coat looks dead and worn. Her hair is matted. She has never looked worse. Regrets slink after her, pause in confusion, and turn back, but I do not want them any more. Two years ago she was not like this. Yes, old and unkempt, but not this bad. The coat had still hoped for recovery.

When it had first happened, I had argued and pleaded with her. I had voiced my anger and flailed my arms, all to no avail. She spat out the pills, got better, got worse. The roller coaster went on for more than a year, until she broke again. By then the love lay not in tatters, but lifeless, dry, and dead. A zombie, it struggled back to its feet as bitter anger, even hatred. The end came for us when the end had come for Esther, at the end of that long, wet trail of gore.

Twenty six years later came the letter. I had been shocked at the picture inside, but the words had begged forgiveness. The woman I had known could not have written it. Maybe it was a friend who prettied it up, a pastor, a counselor, or just someone she had met. She was broken, yet something of her was still there, like the fragment of a shredded photograph, and it was that part which reached out with tremulous fingers, uncertain, but with some sort of impertinent need.

She is a tiny figure now under wintry trees. Park benches line the gravel path, cold and uninviting. Sounds usually travel in the crisp air, but the city is strangely still.

I think of the last words she said to me.

I think of the traffic, of the ice floes, and the ducks.

I think of a girl named Esther, who came within three months of seeing the light of day.

She is waiting for me.

Only when the tiny figure has vanished into the distance, do I understand.