The morning air was chilly as you stepped from the auto-rickshaw. While you waited for Nishok, your translator, to pay the driver, you wrapped the fabric of your chunni more closely around your bare arms, grateful for its warmth.

A post-dawn mist was slowly clearing, dissipating in wisps like melting snow and taking with it the remaining darkness. The village was being revealed like a magic trick. Shades of yellow ochre began to appear on the dusty village path, interspersed with grey stone. The shapes of the cement houses, in various stages of completion, were gradually defined. Slowly, shapes became three-dimensional and the scene took on a life of its own.

Like a sedated creature coming to consciousness, the village was just beginning to stir. In the drowsy confusion of daybreak, the younger women were starting their routine breakfast preparations. Pans clattered and an aroma of burning wood filled the air. Soon, the younger women and men would go to work in the fields.

Akhil, the village head-man, left the group of men he had been speaking with and approached you. He was sturdy, middle-aged and imposing. A striped dhoti had been untied from around his hips and allowed to hang sarong-like around his legs. He was cleaning his white teeth on a piece of neem bark.

Taking the stick from his mouth, Akhil invited you and Nishok to sit on two plastic chairs on his porch. Soon, a young woman – his daughter – appeared with a small tray bearing two stainless steel cups of chai. She was immaculately dressed in a sari and her long, luxuriant hair was pinned neatly into a bun. She dipped her head shyly as she offered the drinks.

Having travelled through the night to get there, the sweet drink was always welcome. You sipped the tea, passing the scalding stainless steel cup between your hands. As you and Nishok discussed your plan for the day with Akhil, a familiar gathering of children began to form around you. You spoke to them with your basic Telugu, struggling to remember the grammar and sounds you had just started to learn. It was the first language you had learned without an alphabet and you practised the swirling script over and over again in your room at nights.

They were on their way to school wearing clean blue and white Western-styled uniforms – the boys in shorts, the girls in skirts. The girls’ locks were tidied into tight plaits, the boys’ fringes brushed flatly off their faces. They could have been school-children from any country in the world. As they questioned you and giggled at your language attempts, you glanced across at the row of elderly women seated in their usual position at their porches.

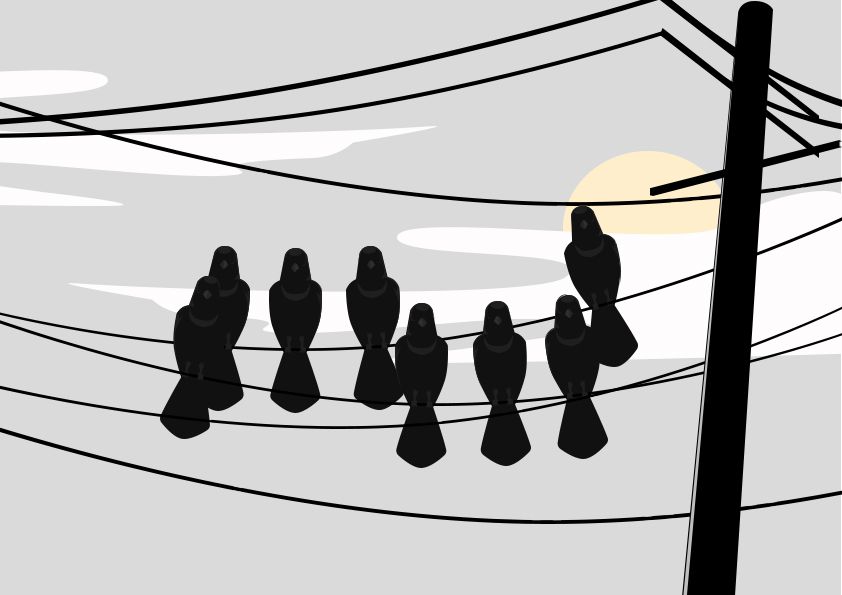

The women were perched like a line of crows on a telephone wire as they waited for their breakfast. Their keen eyes wandered over the village, their voices cackling to each other loudly, checking that nothing was amiss after the night’s slumber.

In India, the loss of awareness during sleep meant heightened vulnerability to dangers like tigers, scorpions, king cobras, mosquitoes and spiders. As a foreigner, you knew the risks only too well. They had made you more philosophical about life, acutely aware of its fragility, but also of the impossibility of clinging to it so desperately that you forgot to live it.

For the past 6 months, these old women had been there, watching you critically. Although you were middle-aged, they’d made you feel like a rebellious teenager, as though you represented some kind of threat to the status quo that held their already precarious existence together.

Nishok was a polite young man from the city, studying for a Ph.D. in Economics. He seemed oblivious to the stares of the old women – but, then again, he was not their target. It was you who was somehow offensive to them, you who was perceived as committing some kind of unspecified misdemeanor.

Each visit, you passed the women with Nishok at your side and gave a confident Namaste, palms pressed together and head bowed. It always surprised you how desperately you craved their approval, even as you affected unconcerned bravado. But there was no mistaking their disdain for you.

On this particular morning, your arrival in the village gave rise to intense excitement. You had brought the photographs which you’d taken during previous visits. The villagers crowded around eagerly as you began to distribute the images. Many did not own cameras or camera phones, so this was their first experience of seeing their faces, and those of their families, immortalised in print.

The photos made the people warm to you like nothing before. You could feel their joy and the goodwill directed at you as the source of it. It was the first time you’d experienced some semblance of acceptance in a context in which you had been, and remained, alien. The strangeness of your white skin, language and height had suddenly been transformed into something pleasantly exotic, rather than alarming.

Out of the corner of your eye, you were aware of the elderly women glaring from their porches. You sensed they were perturbed by this reception, disgusted at their fellow villagers for selling out. And you instinctively knew that this was to be the morning – today there would be a showdown.

Feigning self-assurance, you set off with Nishok to your first interview of the day. The route took you past the old women. As had become your custom, you made a quick check to ensure that the folds of your chunni were arranged neatly across you chest to avoid any accusation of immodesty.

Your head was bowed, and your palms joined for the routine Namaste, when you heard the women addressing Nishok harshly. He answered respectfully, using the polite form of Telugu – but you had learned enough of the language to know you were being spoken of disapprovingly.

‘What did they say?’ you asked, at the same time giving what you hoped was a pleasant smile to imply lack of understanding.

Nishok seemed embarrassed.

‘What did they say?’ you repeated, this time more firmly.

He stuttered: ‘they asked why you keep coming here, why you don’t just stay in your own country, in your own home, taking care of your husband and family.’

The familiar Western reaction, bred through decades of feminism, rose like bile in your throat.

‘Tell them I don’t have a husband or family,’ you said, trying to keep your voice steady. ‘Tell them women are free to live any life they choose. Tell them…’

You faltered, excited emotions hindering articulation. You took a breath.

‘…tell them women can look for meaning in all sorts of ways and…’ You tried to get to the crux of what was really upsetting you. ‘And ask who are they to judge?’

Nishok looked at you, shocked.

‘Tell them,’ you insisted.

The women, a murder of crows, realised their comments had struck a nerve. They closed in for the kill and quickly surrounded you. Nishok began to translate, his voice almost pleading.

As he continued, the women exchanged increasingly outraged looks. Their cackling became fierce, their body language animated. They began to shout at you simultaneously, like Indian Furies, their saris flapping like wings with the force of their wrath. Their small lively eyes blazed and the virtually toothless mouths and deeply cracked faces became vibrant with indignation at your now defiantly defended difference.

‘What are they saying?’ you asked, simultaneously horrified by, and fascinated at, the spectacle.

Nishok looked at you with what appeared to be pity.

‘You really want to know?’

‘Just give me the highlights.’

Nishok’s voice was soft.

‘They ask who’ll take care of you when you’re old.’

You stood, frozen. You could feel years of cultural conditioning beginning to unravel.

‘Who’ll take care of me? But I…’

You looked at them. Their wrinkled, wise, dark eyes had become still, watching. They saw you were wounded and suspected they had delivered what could well be a fatal blow. But this was a fight from which you no longer had the option of withdrawing.

‘I can take care of myself. Tell them that.’

You tossed your head back and hoped that the hollow ring of the words in your own ears would not translate.

Nishok again seemed awkward but did as you asked. The women looked at you bitterly, cawing softly to each other, then slowly retreated to their porches.

You moved on, obstinate but battle-scarred, leaving the site of what you knew had been a pyrrhic victory for all.