I met Justine Carterette’s father in middle school. I was invited to some awkward adolescent gathering in her basement with flat soda, stale chips, and boys and girls sitting on opposite ends of the room. Between the two groups there was a massive sound system and record collection belonging to Justine’s father that we were forbidden to touch. I only saw Mr. Carterette once that night. He was sitting on the couch in the dimly lit living room, watching a black and white movie. He saw me, gestured ambivalently, and said, “How’re ya?” in a tone that told me he required no response.

I became better friends with Justine and she held further gatherings, ones with high school transgressions. Those nights ended in swaying vision and entwined tongues and, as the year went on, a soundtrack provided by Mr. Carterette. Still not allowed to touch the record collection or the soundsystem, he left a piece of paper and a pen on the coffee table so we could scrawl a list of our desired albums. He would come down, look at the list, and put on the first record. Once it was playing, he would return upstairs until he heard the music stop. Then he’d come down and play the next record on the list. He never said anything about our choice in records or about the stench of cheap whiskey and sweat. He accepted it all with a placid smile, as if he knew that someday, surely in some far off future, he would hold on to the memory of those nights as a place in which to retreat.

By junior year we fell heavily into pot and I fell heavily in love with Justine and soon it was only us in the basement, blowing smoke out the window and listening to records we were still unable to touch. We made a routine of checking tracklists so that when the last song started we could clean ourselves up, fix our hair, put back on our discarded clothing. Again, Mr. Carterette betrayed nothing, just smiled that vague, easy smile.

Only after Justine and I made our relationship official did Mr. Carterette request we all have dinner. And though I’d known him since I was eleven, I’d grown used to him as stoic and nearly non-existent and was terrified to meet him.

—

Mr. Carterette opened the door for me when I arrived for dinner. Greeting me, his voice was higher than our monosyllabic meetings had led me to believe. There was something welcoming and calming in not only his tenor, but his cadence as well, a suggestion that he already approved of me. Justine was seated at the table and looked immensely pretty in the soft light Mr. Carterette had set for us. I sat next to Justine and Mr. Carterette took a seat at the head of the table, said the name of the dish he’d prepared, and added, “It’s French. Justine tells me you like the French?”

“French writing, at least,” I said, looking to Justine and then back to Mr. Carterette.

Mr. Carterette seemed pleased.

“Justine says you are a writer, is that right?”

“I hope to be one day.”

Again, he seemed pleased.

Mr Carterette spoke for most of the evening. He started with the French writers he knew well, Balzac to Rimbaud to Proust, and even spouted a few lines of verse in the original language that I did not understand but nevertheless admired. From there he moved to French music which morphed into an explanation of German music and the influence of Berlin on electronic music and by the end of this journey both our plates were untouched. He reminded me to eat and I did so quickly to get back to his dissertation. But he took his time and I instead spoke to Justine who’d been listening, bored but grateful, to her father’s speech. She told me how much her father liked to have someone who appreciated all the same things he did. I realized then that she too had been nervous about dinner, which was odd, as she never once seemed nervous or even concerned with having us in her basement, drinking, smoking, and exploring one another.

Mr. Carterette finished his plate, placed his fork down, sighed, and then pushed himself away from the table.

“I’ve something to show you,” he said and stood up. “Follow me.”

I stood and looked at Justine. She smiled encouragingly.

“He’s very excited to show you this,” she said but didn’t get up.

I followed Mr. Carterette up the stairs from the kitchen to the second floor and he paused before the door at the end of the hall. A thin sheet of light came from beneath it. He smiled over his shoulder and opened the door.

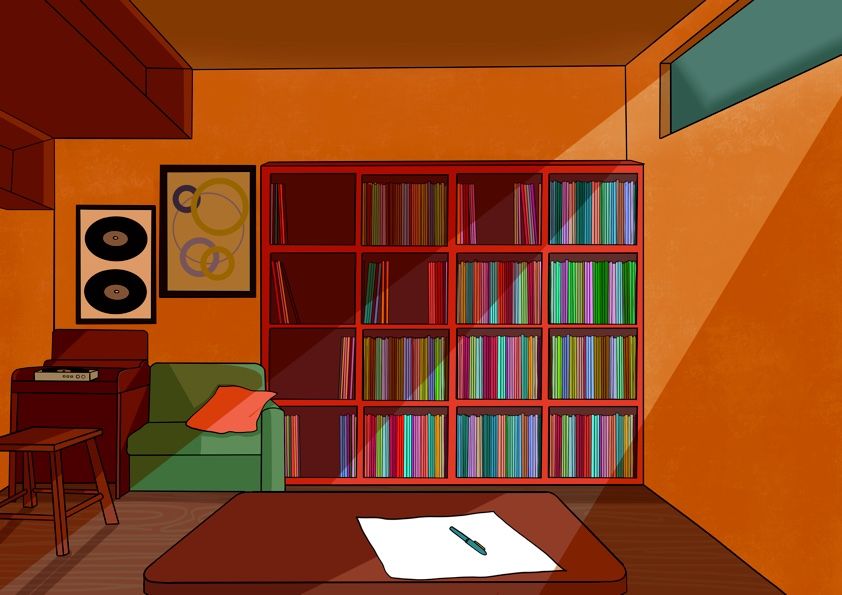

The walls were lined with books, clothbound, gold lettered. In the center of the room was a rich, wooden desk with a single green hooded banker’s lamp on it.

“Pretty nice, huh?” Mr. Carterette said.

I walked the perimeter of the room, standing on tiptoes then crouching on my heels, looking at every single author and title and periodically running my finger down the spines. While I explored, Mr. Carterette stood watching, his gaze neither oppressive nor lascivious. It was immutable, calm, and suggested that this had been planned and everything was going accordingly. At one point, Justine appeared in the doorway, leaning casually against the frame. She was smiling too, though there was something different in her smile. Something practiced and not wholly real.

After dinner, Justine and I retired to the basement and had arms around each other when she said, “Thanks, by the way.”

“For what?”

“Humoring my dad. I think he needed it.”

“I wasn’t humoring.”

She smiled, joyless and placating, and then kissed me.

—

I began arriving at the Carterette house even earlier than usual. Mr. Carterette would grab me as soon as I walked in the door, eager to show me a record, a book, an instrument. He would run recipes by me that he was considering making, all French, despite the fact that I had no culinary experience. Some nights he all but demanded that we—himself, Justine, and I—watch a movie together from his vast collection of classics. He would choose the movie and talk through it, listing factoids and opinions and other movies that shared the same “connective tissue”. Very rarely did he direct these tirades toward Justine.

In my own life, I had few people so passionate and knowledgeable about the things in which I was interested. My parents, being supportive, tried but there are certain things you cannot fake. So I had no problem with Mr. Carterette’s eagerness, especially since, after whatever lesson he had for the day, he would let Justine and I retire to the basement undisturbed, save his switching of the records.

In that basement, a Pharoah Sanders record playing, our eyes red, Justine said, “I’m sorry about my dad.”

“Don’t be. I like it.”

“You aren’t getting sick of him?”

“Of course not. And besides, even if I was, I’d tough it out to see you.”

I thought myself charming but Justine replied, “You can tell me if it’s too much. There are other places we can go.”

“I was just kidding. It’s fine. Really.”

But the school year ended, summer erupted, and there was no longer anything to occupy the day. Mr. Carterette’s demands grew. Soon, just to get a few hours alone with Justine in the evening, I’d have to arrive around noon so Mr. Carterette, who worked from home, could exhaust himself by sunset. And despite him demanding nothing other than a fixed gaze and occasional affirmations, dealing with his manic energy left me too tired to do anything but lay in Justine’s lap.

Soon the excuses began. I was sick. I had a family engagement. I had a prior plan with my friends. I didn’t make these excuses to Justine but rather to Mr. Carterette. He’d call me from Justine’s phone and protest. A few times, in hushed breaths, he asked if Justine and I were fighting. I assured him we weren’t and promised I’d see him soon.

Justine and I began meeting at my house, at friends’ houses, in our cars in empty parking lots. We explored every option of places where we could be alone without having to first run the gamut of her father’s interests. We’d lay in parks from the sultry heat of noon to the pale cool of night, enjoying the breezes and stars, dreading having to say goodbye and leave separately, so as to not let on that we’d been together.

At this time, something conservative in my mother acquiesced and she allowed Justine to spend the night at our house, on the stipulation that my bedroom door remain open. We didn’t mind. Sex could be had anywhere but there is no substitute for laying in bed with someone you love, the docile comfort of bodies and blankets, the supreme illusion of safety. Justine began sleeping over most nights a week, which irritated my mother until Justine’s presence in our home became just another element of routine, as expected and unconcerning as a mail delivery.

Mr. Carterette of course protested in a roundabout way, saying that it was unfair to demand so much of my parents and that we could stay at his place at least some nights a week to ease the burden. Justine explained that I had a full sized bed and she a twin, which could not hold two people comfortably. A lie on both accounts. That excuse worked for a week before Mr. Carterette bought Justine a full sized bed.

We returned to the routine of my noon arrivals, finding that the opposite, a very late arrival with the disclaimer that I had a long day did nothing to dissuade Mr. Carterette. Again I was nodding, offering agreements, and falling into Justine’s new full sized bed beyond burnt out.

One night, after a tangent on the importance of John Ford’s Stagecoach and a late dinner of sole meunière, Justine and I were in bed. I was resting on her shoulder and she was twirling my hair and we were both breathing harshly in an attempt to extinguish the tension. I knew she was going to apologize again and I would again assure her that I did not mind dealing with her father. But this time she would know I was lying and that my excuses for not visiting, not seeing her, were becoming more and more frequent as a consequence. But our harsh breathing was interrupted by a fierce hammering on the front door which was located right below Justine’s bedroom. The hammering was accompanied by the rattling of bracelets, weighty and no doubt expensive.

Mrs. Carterette.

Mrs. Carterette, nee Holbech, while loving and convivial, was an extraordinarily determined woman with a prominent role near the top of the company where she worked. Something to do with paper products, I think. The job made her a good amount of money but it also kept her incredibly busy. While logic suggests contention between Justine and her mother, it was quite the opposite. The increased time away for work coincided with Justine’s adolescent desire for independence and frequent phone calls while her mother was gone were enough for Justine. At least, that’s what she told me.

I knew very little concerning Mr. and Mrs. Carterette’s divorce. Justine knew very little as well, it seemed, because all she said was that she really didn’t remember a time when her parents were together. She assumed this made it easier, as we’d witnessed many friends spiral after their parents’ marriages dissolved.

I lifted myself from Justine’s shoulder to ask if we should go down to meet her mother, but Justine pulled me back down. I heard Mr. Carterette lumber down the hallway. I heard the door hinges whine. I heard him mumble Mrs. Carterette’s name. Then I heard her yell.

Mrs. Carterette’s voice was husky, the same rasp beginning in the edges of Justine’s voice, and most of what she said was lost to us. But none of the fury was. She ranted, using perilous and foreboding phrases like “You’re doing it again” and “How many more times?” and “Do you want to lose her?”. Waves of pleasure and guilt rode my chest in tandem. I felt the weight of Mr. Carerette’s oppression lifted off me. But then I imagined Mr. Carerette’s impish slinking from Mrs. Carerette, wounded and pathetic, like a dog punished for an accident on the carpet. I didn’t feel sorrow or even pity. Only shame.

While her mother was yelling, Justine just stared blankly at the ceiling.

—

Things were easier from then on. Mr. Carterette would greet me distantly, but not cruelly, then allow Justine and me to do whatever we pleased. We did not treat him as a pariah and occasionally Justine requested he join us for dinner or sit with us while we watched a movie. Sometimes he obliged, casually, and other times he declined, cordially and seemingly unwounded.

The rest of our senior year passed by coolly. Justine got accepted to a school across the country and I got accepted to a state school and we buried the natural conclusion of such an outcome in endless proclamations of love. Even when summer came again, we did not discuss it. Even as we bought new outfits, textbooks, and sweatshirts with logos and mascots. Only on those final days of August, before orientations and roommate assignments, did we speak about it. Or rather, Justine explained. She was leaving and leaving me. She said things that I hated then but understand now. Maybe I understood them then too but found it impossible to admit something so painful could also be correct. I petitioned, like a fool, rattling off an endless stream of memories and promises, and, with impeccability, Justine said, “All those things were true and we’ll always have them.”

I didn’t see her off. I didn’t say goodbye to her. Or Mr. Carterette. I made a conscious decision to fade away, to cut all ties, to become a ghost in her life. And his. And anyone else who knew us.

—

By junior year of college my journey to ghostdom was all but abandoned. I tried intensely my freshman year to drink myself into an interesting curmudgeon, a drunkard artist whose pain was writ large in his face, but found that resulted only in thirty excess pounds and a bunch of blank pages. So I refocused, pushed the drinking to the weekends, and gave myself a strict regimen of one thousand words a day that I sometimes almost kept to.

I was home for Thanksgiving that year and the day before the holiday my mother tasked me with going to the grocery store to get the cranberry sauce she’d forgotten. It was packed with people. Upon my few visits home the prior years, I worried that some face from the past might be riding by on a bike or walking a dog and would see me and think, “My god, what happened?”, or worse yet, halt their bike or heel their dog and ask me how I was. But then, in the supermarket, I was eager for old faces. I would’ve been happy to shake hands or hug some former friends and open up about myself, hoping to encourage the same in them. But I saw no one I knew. The faces were those of strangers and I realized, plucking a can of cranberry sauce from the shelf, that this was no longer really my hometown. It had shifted beyond me. The demographics were different, the people either too old or too young. The woodlands had been paved over and replaced with townhouses. The off-brand supermarket was now a Target and that Target had swallowed up the diminutive liquor store next door that never used to card.

I weaved through the crowd of shoppers. The registers were in view when a head of thinning gray hair blocked my sightline. I stepped to the left and the man did the same. To avoid the awkward dance of silently trying to get around him, I tapped him on the shoulder and began saying, “Excuse me, but can I—”

The gray head turned and facing me was Mr. Carterette. He didn’t seem to recognize me.

“You need to get around?” he asked.

“No. Yes, but…you’re Mr. Carterette, right?”

“Yes?”

I told him who I was and held my arms open, smiling like a gameshow host. He seemed to search his memory, as if it had been decades and our acquaintance merely one night of lost revelry.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “You used to date Justine, yes?”

I’m not certain why, but the designation of having “used to date Justine” hurt me. I suppose it was limiting. I was not just one thing—an ex-boyfriend—but multitudes. I suppose it also hurt because, despite his overbearance and demands, I considered myself more to Mr. Carterette than just his daughter’s boyfriend. Though, in truth, I don’t think I ever considered him more than Justine’s father, not at least until right then. And I suppose it hurt too because Justine’s name still hurt to hear. I hadn’t spoken to her since high school, save some short, shameful phone calls freshman year. By all accounts, from friends of friends, she was doing well. I never probed any deeper.

“Yes,” I said.

“Well now,” he said, slapping me on the shoulder, “how are you?”

“Good, good,” I said. “And you?”

“Surviving,” he said.

The basket he was holding contained a small turkey and a box each of stuffing and instant mashed potatoes.

“Just a small dinner for the holiday,” he said after he saw me looking.

“Of course,” I said.

“Justine’s coming for an early dinner today, if you’d like to join.”

I squeezed the can of cranberries. I’d spent the last two years growing past poor decisions. I’d learned to see that fork in the road, one side populated by self-destruction, the other by solemnity, and choose the one that would lead to a good night’s sleep. I was there again, that old fork, that well trodden fork, that Frostian fork.

“I’d love to,” I said.

“Great. She’s actually coming by in a little bit, if you want to come over right away.”

I agreed, telling him that, after I dropped off the cranberry sauce, I would swing by. I actually said, “swing by” hoping to seem nonchalant, so if Justine arrived before me, he could tell her that I would be “swinging by”. So casual. So carefree.

—

I pulled into Mr. Carterette’s driveway and saw the gutters were leaf-clogged and the groutlines had grown mossy. The living room bay window was rife with smudges. I knocked on the front door and Mr. Carterette opened it immediately.

“Hello again,” he said, stepping aside and waving me in.

“Thanks again for the invite.” I wiped my shoes on the carpet.

“Of course. Turkey is in the oven but it’ll take some time. There’s some finger food in the kitchen though. You know where it is.” He shut the door behind me.

The house was gray and dark, even in the foyer where the light was on. In the living room the television played a sitcom without any volume. The shelves neighboring the television, once housing endless spines of DVDs, were barren. In the kitchen, the sink was full of dishes and glasses and on the table was a plate of Ritz crackers topped with slices of plastic looking cheese.

“Can I get you something to drink? Beer? Wine?” Mr. Carterette moved into the kitchen behind me.

“Any beaujolais?” I asked, giving him a reminiscent smile.

He crossed the kitchen, opened the cabinets and looked for a moment. “Looks like I’ve only got some red blends.”

“That’s fine. I was just kidding anyway.”

“Of course,” he said, not laughing, not smiling, not even looking at me.

He took a bottle from the cabinet and a dust-kissed glass from the counter. He set the glass before me and filled it with a Barefoot red blend.

I drank the wine and picked at the cheese and crackers. Mr. Carterettte sat across from me, sipping wine and smiling distantly. He picked up a cracker, placed it on his plate, and left it there, occasionally lifting it to chin height amidst conversation, only to return it to the plate once he was done talking. We talked mostly about me, which was odd. But he was still as exacting and exhausting. What classes are you taking? What books do you have to read for those classes? What did you think of the first book? The second? And so on. Between questions, he drank. His lips were stained red by the time he had to untent the turkey. While he was hunched over the open oven, wincing in the heat, I told him I had to go to the bathroom. He waved in the general direction of the stairs.

I climbed the small staircase into the darkness of the upper hall. I walked toward the bathroom without looking at Justine’s bedroom door, making it there without her doorknob so much as kissing my periphery. I urinated then washed my hands, chuckling at my red cheeks in the mirror. I left the bathroom smiling, forgetting my intention not to look at Justine’s door. But I did and turned away rapidly, like a groom who’d accidentally seen his bride’s dress before the ceremony, and ended up looking at the door of Mr. Carterette’s office at the end of the hall. No light came from beneath the door.

In the kitchen, Mr. Carterette cursed accompanied by the sound of pots spiraling on the floor. I stepped to the office door and opened it. The bookshelves were gone. As was the desk and the banker’s lamp. There was only a treadmill piled with clothes and unlabeled cardboard boxes along the far wall. The room smelled stagnant. I closed the door.

Back down the hall, I stopped at Justine’s door. I sighed and opened her door too. The room wasn’t lived in. Her bed was still there, comforter of blue flowers neatly tucked and folded. Her desk was vacant of anything that would suggest it’d been used. The necklaces that used to hang from her lamp were gone. Photos of old friends, of the two of us together, were missing from the mirror’ frame. The sodden nature of her room, the sunkenness of a place I once loved, once never wanted to leave, saddened me. But it too, like the town, had moved beyond me and my time with it. And with that, I felt a sting of what I assume was maturity. But it was a pleasant sting. Perhaps the indicators of adulthood are not taxes and children but resigned feelings of longing.

I was closing the door, proud of myself for that fleeting feeling, when I noticed that all the photos that had remained in her room were of her and her father. Listening for Mr. Carterette, hearing him singing to himself in the kitchen, I stepped into Justine’s room. I opened the drawers of her nightstand. Nothing. In her bureau, not even children’s clothes. The closet was vacant save plastic hangers that danced lightly when I opened the closet door.

“Get lost?” Mr. Carterette said from the doorway.

“Uh, ah, no,” I stepped into the middle of the room. “Just, you know…for old time sake.”

“Mhm.”

Mr. Carterette leaned casually against the door frame.

In the kitchen, the oven timer went off.

“Turkey’s ready,” he said.

“Oh, nice.”

The timer kept ringing.

“She’s not coming, is she?” I asked.

Mr. Carterette smiled and lifted himself from the doorframe.

Once the timer stopped, the oven door opened and closed, and the smell of unseasoned turkey filled the house, I went back to the kitchen.

“Light or dark?” Mr. Carterette said, brandishing a large carving knife.

“Dark, please,” I said, taking my seat.

He hummed something sullen while he carved.

He set a plate of poorly cut pieces of dark meat in front of me and took a seat across from me with nothing but his wine glass.

“Dig in,” he said.

And I ate. It was the first silence of the night. I tore meat from the bone and reached, gasping, for my glass of wine. Mr. Carterette watched and sipped from his glass. By the end my plate was clear and I sat back with a distended stomach.

“That was good,” I lied.

“Hey,” he said, sitting up. “Follow me.”

He got up, gathered my empty glass from the table and a bottle of wine from the cabinet. I followed him downstairs to the basement door and together we descended.

The basement had a gray stillness similar to the rest of the house, but the tables and chairs were not caked in dust and the couch had a blanket on it that was not neatly folded but spread and lived in. And, while the rest of Mr. Carterette’s interests seemed to have vanished from the house, his soundsystem and his records were still there.

“Pick an album,” he said.

I scanned the records, smiling at old favorites, feeling again that proud, pleasurable sting.

“Blood on the Tracks,” I said.

“Ah, Dylan. You always liked Dylan, right?”

“Yes,” I said, lying again. But what harm is falsifying a pleasant memory?

He sat on the couch and unscrewed the wine bottle.

“Are you going to play it?” he asked, doling heavy pours into each glass.

“Don’t you need to put it on?”

He stopped pouring. He looked up at me with shining eyes, cresting with joy and sadness and appreciation. Then he waved a flippant hand and said, “You do it.”

For the first time, I touched one of his records. I drew out the album with turkey grease covered hands and set it on the turntable. I pressed the button to get it spinning. I laid the arm atop the record. It garbled for a moment and then the first notes of “Tangled Up in Blue” came through clearly.