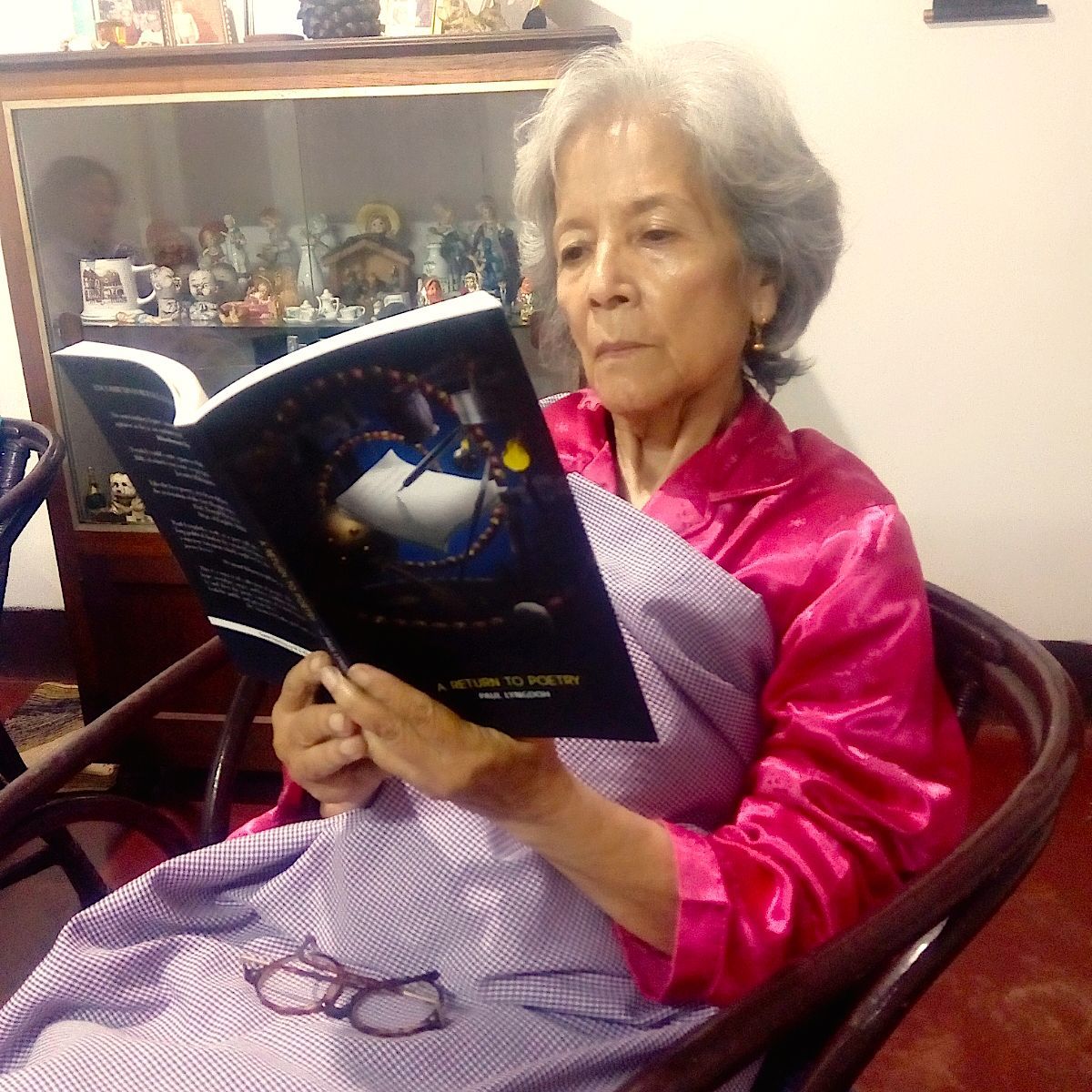

It is not every day that we come across politicians who are frank about the world around them when it comes to writing. At a time when interest in poetry has taken a back seat, and when the youth are more likely to pick up a copy of ‘Twilight’ than a collection of poetry, how will ‘A Return to Poetry’, stand a chance at reviving passion for the art form? The bilingual anthology of poems, ’A Return To Poetry’ by politician, Paul Lyngdoh, bears testimony to the changing times and raw emotions that the poet expresses towards politics, his native hills, and the dwindling Khasi customs.

On reading ‘ A Return to Poetry’, a second collection of poems written after , ‘Floodgates /Ki Khyrdop’, a book published twenty-seven years ago, one can draw a comparative analysis of life in the Khasi Hills during the simpler ‘ Eolithic’ age of our forefathers and during the period of 1991-2018 in ‘Shades of what we call modernity’. The changes that unfold between such times are evidenced.

‘A Return to Poetry’ was released on 22 September, 2018, by Father Stephen Maveley, the Vice Chancellor of Don Bosco University, Guwahati, who also served as the Chief Guest in the presence of author and Director of IGNOU, Dr. Ananya Guha, former Home Minister, RG Lyngdoh, folklorist and educator at North Eastern Hill University (NEHU), Professor Desmond Kharmawphlang. That the room for the launch was full was refreshing to say the least. The book’s release coincides with the reality of socio-political occurrences such as that of the demand for the Khasi language to be included in the 8th schedule of the Indian Constitution, the aftermath of the violence in the Punjabi-slum area of the city, decriminalizing Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code(IPC) which criminalizes homosexuality and the creation of the Khasi Social Customs of Lineage (second amendment) Bill 2018.

Notable writer, historian, and lawyer, the late Khushwant Singh, described Lyngdoh by saying, “…he is as powerful an agitator as he is an embittered poet”. In the words of Dr. Ananya Guha, “Lyngdoh has been writing for two and a half decades; the poems go back to the past and come back to the present; they quintessentially talk about a love for the land̶ the culture and the beauty of these hills”.

In ‘A Return To Poetry’, he claims that poetry is ‘..an asylum whenever my faith in humanity ebbs’ . Poems like ‘Umiam’, ‘Nohkalikai Falls’,’ After Visiting The Backwoods Of The Khasi Hills’, ‘The Hills Resonate’, ‘The Picture Of Poetry’ and ‘Songbird’ speak about his deep-rooted passion for nature and his native hills. Although the book is entitled, ‘A Return To Poetry’, it does not convey an escapism from the reality of the world, with its political fiasco, wanton destruction of Mother Earth and the dearth of brotherly love, but more so an escapism to a world that he has cushioned for himself, where he can vent out his innermost feelings and frustrations which cannot be confronted aloud. The reader grasps an understanding of the social and political situation of the late 1980s and the 1990s within the Khasi Hills, specifically Shillong. Poems like ‘Domiasiat’, ‘July 1992’, ‘Sohra’, ‘November,1993’, the collection of poems, ‘Dance of Democracy’( I-VI) ,’March On’, ‘A Return To Poetry’, ‘Signs of the Times’ and ‘July 17, 1989’ speak on this. Then there are the patriotic poems such as ‘My Homeland’, ‘To My Native Land With Love’, ‘Here in our Land’, ‘Shillong 1997’, ‘The Monolith Laments’, ‘Under The White Man’s Sky’, and ‘My Ancestry’.

Desmond Kharmawphlang emphasised that Lyngdoh had succeeded in amalgamating politics and art. He says about the book, ”Although Plato said that there is a marked difference between poetry and politics, yet I have met poet singers from Philippines, Australia and the Balkans who are leaders of their community”.

Poems like ‘For Sale’ talk of the changes that the Khasis have imbibed, away from ‘(their) pride, values, work culture, our sense of shame, our collective conscience.’ Also important are the lines , ‘For sale this battered autistic land with all its lucre laden earth; precious minerals, medicinal herbs ; and trees and fields and waters; all these and all else’. And, “For sale our cumbersome, anachronistic tribal roots … and have become a constant source of embarrassment.” In ‘Shillong, 1997’, Lyngdoh speaks about the Shillong that was deified and revered by one and all in past ages, but by 1997, ‘myriads of monsters (such as justice through violence, fear and hate) suckle (her) dried breasts and, like a prostitute, (she) embrace them all without a hint of reluctance’. The images drawn are fanciful yet direct our attention to reality. In another poem, ‘The Lament of Ramew’ (Mother Nature), he talks about how nature, the divine mother and provider has been sold off by her children ‘to perform a striptease, and now even (her) underclothes have been torn to shreds.’

In ‘A Return To Poetry’, he talks about a necessary return from a world of violence, scams, deception, hypocrisy and the likes of it found in present day social conditions. Images painted through the lines, ’words like sacrifice, loyalty and trust are liberally bandied about like free condoms in an AIDS-awareness campaign’ speaks about how words are used as mere tools to prevent an outbreak or fallout in the entire system that is already diseased but is only effective to a certain extent, like the contraceptive. And in ‘Signs of the Times’, the lines, ‘Two warring political figures embrace for the lensmen’s benefit…..”Each is trying to figure out where to stab the other from”’ is emblematic of much of the political racket as ‘in the assembly, their leaders conspire over the next round of musical chairs’.

The book in its entirety does not ridicule any one party or thing. In ‘Here in Our Land’, he writes:

‘Here, we even whore out our racial moorings

And blindly gift our virgin maidens

To the unctuous lowlander

For a few years of unearned luxury.

Here we trade dreams and sample with different faiths,

Feigning salvation at the feet of the frenzied preacher

Who has finally found his means of livelihood.’

Referring to the title of the book, he says, “I am writing poems but it does not mean that I am retiring from politics. It is because in them I find peace”. Paul Lyngdoh could in a way be likened to the newspaper boy who cries out the news daily. But Lyngdoh’s is a plea to restore what is lost. And we, his audience are the passers-by who have the option to either listen to him or ignore his utterances.

Paul Lyngdoh’s passion in his poetry which is sometimes graceful, sometimes crass, has no doubt elevated him to the status of a prominent writer of the Khasis. As Dr. Ananya Guha pointed out, ‘It is also the poetry of love for the land, the community, the people when society is in transition, and where the question of the mainstream is always raised as a proof of national identity consensus’.