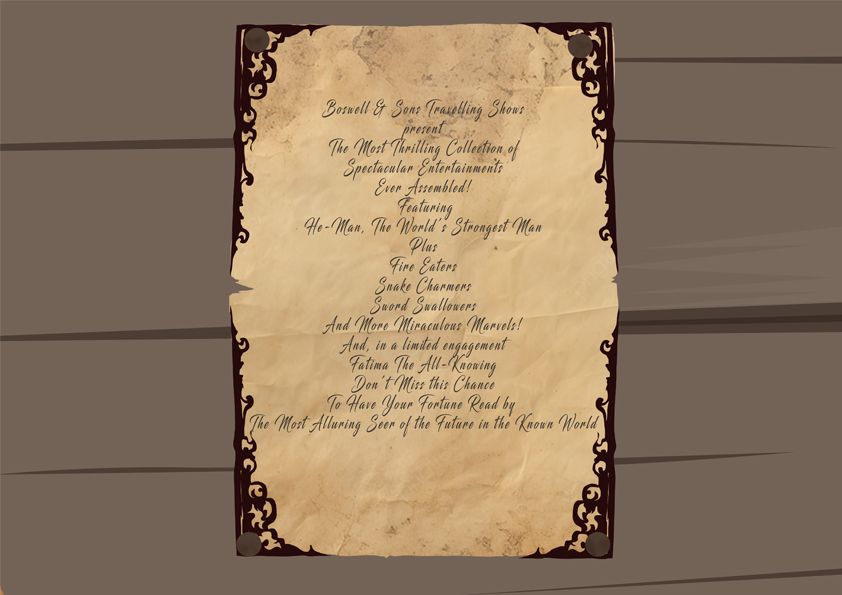

Sophie found the poster in a trunk while cleaning out the attic of The Shack after her grandmother’s funeral. It was trimmed in shimmering gold with letters in brilliant shades of blue and red. She had it framed and hung it on the wall over the sofa in every apartment and house she ever lived in from that day forward.

The Shack was the place where all four of Sophie’s maternal great-grandparents had lived, although the word shack didn’t do it justice. It was more like a castle, made from good solid timber instead of stone. The four of them, along with four others, built the great hall and the first few rooms in 1880.

The original eight had been members of the Boswell branch of the Romany people of the British Isles. They’d come from an area on the border of England and Wales, where people had called them “gypsies” or travelers. There they’d lived in covered wagons – little houses on wheels – and never stayed in one place for long. Once they arrived here in America, where they were often mistaken for Italians or Spaniards, Sophie’s ancestors and their kin had begun to raise their families. Over the years, each generation had added on to the Shack, expanding it until it became the sprawling, mazelike complex Sophie knew.

The eight of them earned a living buying, breeding and selling horses and donkeys on the property surrounding the Shack. They grew much of their own food and remained a somewhat closed community, though they were always on friendly terms with their neighbors. Over the years, the nearby town grew into this city. The horse farm is still there, just over the river on the west side, still owned and operated by the descendants of those eight Boswell Romanies.

They had sailed across the ocean as four couples, and they soon became four families, with twenty-five children between them. There were the Woods (five boys, three girls), the Lees (five girls, three boys), the Youngs (four of each), and the Loveridges (one glorious girl, Vadoma, which meant “the knowing one” in their language). Vadoma was a beautiful child, and she grew up to become a voluptuous woman, with hair as black as the night sky and eyes a shade darker. All the young men in town were interested in her and her generous curves, but there was never any question of her marrying an outsider. She was pledged to the Woods’ oldest son, Harman (or “hardy man” Romany).

Despite their ancestral predisposition to travel, the four couples lived on the horse farm for the rest of their lives. Maybe their long sea journey had been enough travelling. A few of their children stayed close and helped run the farm. But most of them inherited the need to roam. They moved on, west or south, whichever way the wind blew, although they returned from time to time and continued to think of the Shack as home. Some settled in other places and started clans of their own. Others became tradespeople, troubadours, or peddlers as they moved across the continent. And still others, including Vadoma (who, true to her name, had the Gift of Sight, the secret knowledge of things unknown) and Harman (who, true to his name, had grown to be a tall, barrel-chested lumberjack of a man) became entertainers of a different sort, as described in Sophie’s poster.

Professionally, Vadoma became Fatima the All-Knowing, while Harman was known as He-Man, The World’s Strongest Man. They joined the Boswell & Sons Travelling Show soon after they married in 1913, when she was eighteen and he was twenty-eight. For his act he was shirtless, to show his powerful shoulders and broad chest. For hers, she was as near to it as local law would allow. It was uncertain which sold more tickets: her amazing predictions of the future, or her prodigious bosom. The show roamed throughout the northeastern United States, and eastern Canada, living in brightly colored covered wagons, just as their ancestors had back in England. Years later, Vadoma would tell her granddaughter Sophie that those years were the happiest of her life. Now Vadoma’s life was over, and Sophie had inherited her grandmother’s share in The Shack and the horse farm.

Vadoma’s funeral was almost as much of a show as the ones Boswell & Sons had produced. Harman, though ten years older than Vadoma, survived her; and he delivered a eulogy that none who attended would likely ever forget, and few who hadn’t would believe when they were told about it.

Hundreds of Romanies attended, coming from as far as Brazil and Alaska. It was the first time Sophie fully realized the extent of her family’s reach. She’d heard her grandparents talk about relatives who lived in faraway places, but it never occurred to her that there could be so many of them. Her mother, Sylvia (Vadoma and Harman’s daughter), had died at the tragically young age of twenty, just days after giving birth to her only child. Sophie’s father, Patrick O’Malley, had raised her mostly on his own, with the help of his family. And while he didn’t keep her from knowing her maternal grandparents, he did discourage talk of their past or of the rest of their family. As much as he had loved Sylvia, he always harbored some prejudice toward the Romanies in general – and the Boswells in particular.

Still, Vadoma instilled in Sophie a respect for the mysterious side of life, an interest in the hidden truths that few can see. Sophie was not as gifted with the Sight as Vadoma had been, but she was not entirely blind. She often heard her mother’s voice singing to her as she drifted off to sleep, in a language she did not understand. And while she didn’t ever believe she could read minds or predict the future, she had a high degree of empathy for other people’s emotions and circumstances; an ability to sense the innate goodness (or lack thereof) in everyone she met; and a talent for making people feel at ease, seemingly by knowing exactly what they needed. These were valuable skills in her life as a waitress and bartender, making everyone she met (including me) feel like family and making the barroom feel like home.

In addition to all the Romanies, many locals attended the funeral, including myself. As I said, Sophie made everyone feel like family, so her loss was our loss. Neither of the city’s two undertaker’s establishments were big enough to hold the crowd, so the services were held at the Shack. The wake lasted two days and sprawled over the entire property – two days of music, dancing, and laughter, mixed with tears. Two days of wine, whisky and every kind of food imaginable. Two days of people remembering Vadoma, Fatima the All-Knowing, who would make no more predictions of the future and was now a part of the past.

On the third day, the funeral served as a time to honor Vadoma’s memory. Harman hoped it might also serve as a kind of “passing of the torch.” Sophie, at the age of twenty-five, would now be the oldest female family member still living anywhere near The Shack. In a sense, she’d become the queen of the family. Her grandfather had suggested that she move in, since she was now part owner, and that she take an active part in running the family’s business.

Sophie’s father hated the thought, preferring that his daughter keep as much distance as possible from her Romany relatives. The O’Malleys were strongly Catholic; Patrick’s brother, Sophie’s Uncle Thomas, was the local parish priest. Patrick often reminded Sophie that her mother had converted to Catholicism, breaking her connection to her family’s “pagan beliefs,” as he called them, because she’d “seen the light and accepted the teachings of the True Church.” He also said that Sophie’s mother had wanted her to be an active Catholic as well.

To be fair, this was Patrick’s personal prejudice, not one shared by the rest of the O’Malleys. In fact, Father Thomas O’Malley was a great friend to the Boswells, and even purchased a racehorse from them late in his life.

Sophie didn’t particularly like the idea of becoming queen of the local Boswells herself. But not for religious reasons, and not entirely out of loyalty to her father. She was at the beginning of her life as an independent person, having just moved out of her father’s house into an apartment of her own, near downtown. She could walk to her job at The Brat-haus, where she’d been working since she was sixteen, and where she’d just become the main bartender after years of waiting on tables. She felt at home in the restaurant – and she had no interest in the horse business, and no desire to live amid the never-ending activity at the Shack. It was 1965, the world was changing, and Sophie was just coming into her own.

Still displaying some remnants of his youthful, strong-man physique, eighty-year-old Harman stood before the open casket of his wife. “Ladies and gentlemen, family, friends and neighbors,” he began, “thank you all for being here today to remember my Vadoma. Some of you only knew her in her later years, as the old woman at the horse farm. But some of you remember her, as I do, from her youth, when she was the most beautiful woman on earth.”

“There are many things I will miss about my Vadoma. Her wisdom, her smile, her wicked sense of humor. I will surely miss her cooking. She was the finest chef in three counties, as any of you who shared our table over the years can attest.

“I’ll miss her patience and kindness, traits that made her the best mother imaginable to our children, though she was also strict, and with the highest standards. I will miss her generosity. She gave everything she had to give, and expected others to do the same. In this, of course, she was often disappointed. Few people are as quick to share their gifts as my Vadoma was. No one was ever turned away from our door while she lived.”

“She could be vengeful, it’s true. I see more than one person here today who felt her wrath at one time or another. But she always forgave in the end – after exacting due punishment, of course. I’m particularly reminded of the time when Elijah, one of our nephews – I see you there, Elijah – stole a cherry pie that Vadoma had baked. She had planned to bring it to the widow of John McGonigle, the farrier who died after being kicked in the head by one of our young stallions. Vadoma caught up with Elijah just as he was finishing the last mouthful. He was hiding out behind our lower barn, thinking he’d gotten away with his crime, when Vadoma grabbed him by the hair on the top of his head and lifted him clear off the ground. He spent the rest of that summer painting Widow McGonigle’s house and garage, trimming her rose bushes and mowing her lawn – and not having any dessert after dinners, but having to watch the rest of us enjoy our cakes, pies, and puddings. I don’t believe it’s a coincidence that Elijah became a pastry chef.”

After pausing to let the laughter subside, Harman continued. “I’ll miss the way she kept me in line, too, like she did for all the little ones. You all know I’ve had my moments of straying off the path. Just moments, though, for Vadoma would tolerate no more than that. Just one look from her – just that certain glance – and I always stepped right back into line. In my youth, I was known for my strength, but Vadoma had the true strength. Strength of will and spirit, which I never had. I will surely miss having her to lean on.

“But, friends, I will tell you there is something I will miss more than just about anything else.”

Harman turned to face Vadoma, where she lay peacefully at rest in her casket, hands folded across her abdomen. He looked at her silently for a moment, then put his hands on either side of her face and bent to gently kiss her lips. He straightened slowly, letting his hands move down her neck, to her chest. Then, grasping one breast in each hand, he bent again, burying his face between them.

Straightening, he turned to face us and said, with a tear in his eye, “Those are what I will miss the most of all.”

As he walked slowly back to his seat in the front row, some people gasped or cried out in shock. Some laughed. More than a few sobbed. Sophie, who was sitting next to her grandfather, took his hand and kissed it, pressed it to her tear-soaked cheek. None was unmoved.

The service ended, and the casket was closed and carried from the great hall to the horse-drawn hearse waiting outside, with Sophie and her grandfather following, hand in hand. Vadoma was buried on the property, in the family’s private cemetery, beneath a sprawling oak tree.

Afterward, as the crowd of mourners slowly dispersed, crunching dead and drying oak leaves underfoot, Sophie bent to pick one up and handed it to her grandfather. “Isn’t it beautiful?” she said, tracing the intricate veins with her finger.

“You remind me so much of your grandmother, Sophie. You notice the beauty in even the things other people trample on without noticing.”

“I’ll never be as wise as she was, Bapo. I miss her already.”

“Oh, my little one, you are wiser than you think.”

They walked silently back to the Shack as their guests headed home. Sophie lit the burner on the stove to heat the tea kettle. Harman loosened his tie and sat at the kitchen table.

As Sophie set a mug of hot tea before her grandfather, she said, “Bapo, I know you want me to live here, but I can’t. I have my own life, my apartment and my job. You have your nephews and nieces here to help you, and I’ll visit every day. But the life of the horse farm is not for me. Do you understand?”

“Yes, my little one. I understand. In this also you are like your grandmother. You are strong enough to know yourself. Did I ever tell you about when we joined the travelling show?”

“No. Tell me.”

“We had been pledged to each other almost as soon as she was born. They had no other children, her parents, unlike the rest of that generation. They wished her to stay near them, here on the farm. Can you imagine, a girl full of so much energy and power, sitting here and making tea for her parents day after day?

“We were married in midwinter. I had already started practicing with the show, preparing to travel in the spring, and we planned that Vadoma would come with me. Not as part of the show, but simply as my wife. She had always been gifted with the Sight, and even though she was only eighteen at the time, all our family came to her for advice and readings. But for her, it was natural, not something she needed to work at or practice. And she never thought of it as a way to earn a living, certainly not as entertainment or a show.

“But Berty Boswell – my Uncle Bertram, who ran the travelling show – he saw her potential. He was wise in his own way, Berty was. He knew that among the outsiders, it is usually the women who seek fortune tellers. He realized that a girl as beautiful as your grandmother, with her shape, would entice men to also buy tickets to see her, even if they didn’t want a reading, see? He told this to her parents, how he knew that the combination of her gift and her physical beauty would sell twice as many tickets as the old crone who was doing the fortune teller act at the time.

“Well, Vadoma’s parents didn’t like the idea of him using their daughter in that way. They saw it almost like prostitution. They forbade her from joining, demanded that she stay here. And yet I was about to leave with the show and wouldn’t be home for months, and we were just married. It was an arranged marriage, yes, but we truly loved each other, and we couldn’t bear the thought of being parted so soon.

“Vadoma went to her parents and told them they had a choice. They could let her go with me on the road as a free woman making her own decisions, and as a daughter who would always love them and return as often as she could. Or they could forbid it, in which case she would go anyway, with resentment in her heart, and never return.”

Harman and Sophie each sipped their tea and listened to the wind blowing through the trees.

“She was so strong, Sophie,” Harman went on. “So clear about her own self that her parents could not argue with her. They gave their blessing, and we went together on the road. So you also should go on your own road. Only promise me that the road will always lead you back here, at least from time to time.”

“Of course, Bapo. I need your strength still. I’ll always return.”

And she did. Sophie visited the Shack almost daily for the next year, until Harman died. She sold her share in the farm and the property to her cousins, and I helped her invest the proceeds. Even after that, though, she visited the place periodically. I went with her to her grandparents’ grave a couple of times. Harman was buried beside Vadoma beneath the giant oak, with a single headstone engraved with their names and the dates of their births and deaths on one side, and this message on the other:

He-Man, The World’s Strongest Man

Fatima The All-Knowing

Locked in Love’s Eternal Embrace