Sitting at the outdoor café of the Bilbao Guggenheim, I kept looking up to marvel at its beauty while reading the book I’d purchased about it at the gift shop. My son had gone off on an hour-long expedition to photograph the building from all its sides. He and I had visited inside the museum first, while Lionel and the girls sat at the café with Rocco, our chihuahua, who wasn’t allowed in. Now Lionel was in there with the twins.

Despite wanting to be considerate and finish our tour quickly so Lionel and the girls could have their turn, I couldn’t help but linger inside the museum. Not so much for the artwork itself, exciting as it was, including the Yayoi Kusama exhibit I’d been looking forward to checking out. But over the building itself. Whether admiring it from inside or out, it stunned me from every angle.

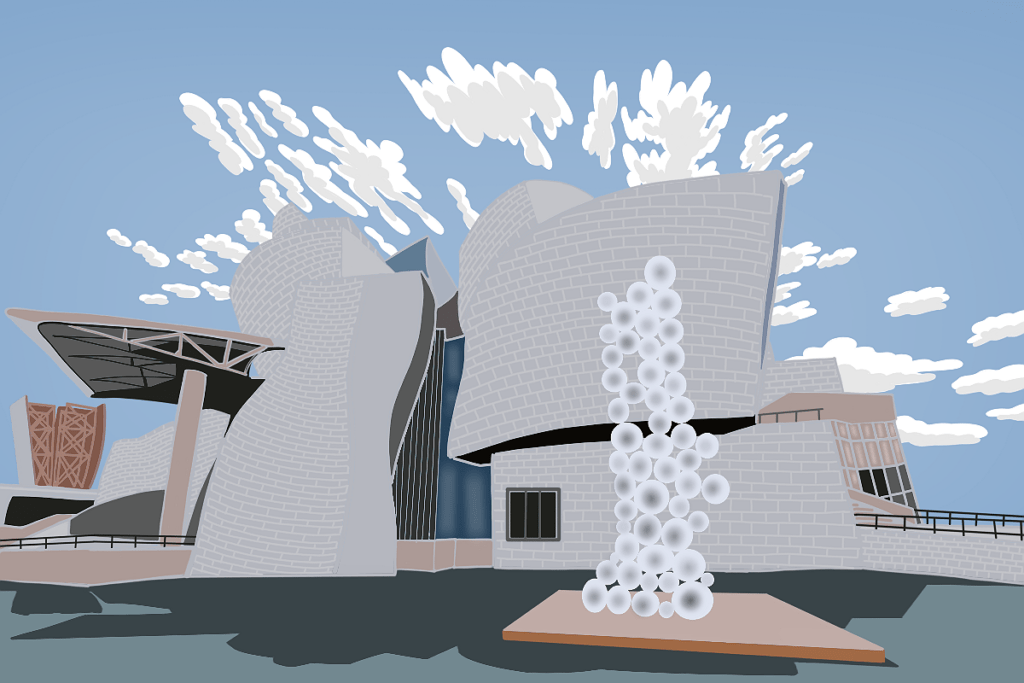

I’d been dying to visit the Bilbao Guggenheim ever since I had first heard about the museum’s opening to great fanfare in the late ‘90s. I was living in New York at the time and had seen images of its unique architecture in the press, though I had to look up Bilbao on the map. Spain was a long way aways for me back then. It was also the first time I’d ever heard of Frank Gehry, and I became an instant fan. His buildings reminded me of Picasso’s paintings. As much as I fawned over Picasso’s genius on canvas, I was confounded by how such artistry could translate into Gehry’s engineering feats. Looking up from my seat at the outdoor café, I gaped at the curvature of the titanium wall that glowed under the soft light of the overcast Spanish summer sky.

Gehry had purposefully designed it that way, in shapes that recall sails, boats, and waves, to honor the estuary on which the museum stood. He chose titanium in a nod to the mining history of the region. The museum had been conceived following the demise of Bilbao’s industrial sector in the 1980s, which had sunk into depression and civil disobedience. Seeking to revive the region as a cultural center and attract tourists, its administrators reached out to the Guggenheim foundation. A mere six months later, architects were being sought to design the future museum.

At the age of 62, Ghery was already an established architect, but not yet the mega-watt star he would become after building the Guggenheim Bilbao. He himself acknowledges that the museum put him on the map as much as it had done for Bilbao; the project truly lifted his reputation and career to new heights.

Having competed for the commission, Gehry’s understanding and care for and the tribute his design paid to the past glory of the region’s industrial labor and trade made possible by the estuary won over the selection committee and made the project so unique.

Touring inside the museum with my son, we felt as though we were inside of a ship, with metal beams soaring every which way, encasing massive windows of clear glass that looked out at the wave-like exterior that was reflected in the curved walls that around us. Unlike most buildings that feel static and passive, Gehry’s building had me constantly turning in circles, looking up and down, searching and absorbing all at once. The choice of limestone, glass, wood, and water fixtures, natural materials that blend well together, fostered a light, airy feel, as though we were floating out at sea.

His defiance of straight lines and proclivity toward curves throughout the Bilbao Guggenheim also remind me of my visit to one of Gehry’s buildings in New York. Several years prior, working as a real estate marketer, I had the chance to visit many residential buildings developed by our competitors in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey. But there was little competition when it came to 8 Spruce. The soring steel towers literally rippled through the New York skyline, giving the illusion of movement and change every time you looked at it from a different angle, or as the sky shifted through the day. So did the interiors. The windows dipped in and out of the living spaces they enclosed, making you feel like you were floating underwater. Gehry had been commissioned to design every aspect of the building, down to the kitchen cabinets and door handles, their wave-like features reminiscent of the shapes in Bilbao.

Designing the interior was a departure for Gehry, who differed from his earlier heroes such as Fank Lloyd Wright, whose work he had studied deeply. Wright and his contemporaries preferred to design both the exteriors and interiors to create a holistic, consistent, seamless experience. Instead, Gehry claims that homeowners should curate their own interior pieces based on their own personal preferences and values. He simply builds the spaces for them to do so. What’s more, his approach to building a home is akin to building a city or village. He sees a home as a collection of objects and space between them. His designs take the empty space into account as much as the objects (or rooms), all while considering how to group them all together, and what relationships they should have to each other. At the same time, Gehry also insists that a house should feel like a place where people can live like humans, rather than be part of a museum experience. Where it feels normal to take off one’s jacket and hang it on the back of a chair.

But alas, Gehry is no longer interested in building houses for others – for rich people who can afford it. He’d been burnt before and prefers to focus on projects that the larger public can use. Though, whenever time allowed, he worked away at building his own dream house, a project that had been years in the making. Aside of time constraints given his impossible travel schedule to the many project sights active at any given time, part of the delay in building his new house had to do with him and his wife having different ideas of what the house should be and him trying to reconcile those different ideas in the final design. I love that his wife asserted herself in that sense. My initial inclination would have been to defer to the expert. At the same time, I can see what a treat it would be to partner with an expert to evolve a vision that he can then build.

Lionel and the girls finally walk toward us after their own visit, looking tired but content. On our walk back to the car, they keep pausing to snap more photos of the different angles of the building’s façade. I take the opportunity to call my mother on video chat, to share with her my enthusiasm over the museum. Though she had traveled in Spain, she never made it up to Bilbao. I move my phone around slowly so that she could take in as much as the little camera allows, hearing her gasp with wonder.

Hey Mom, did you know Gehry’s Jewish? I ask her, knowing the pride she feels whenever someone illustrious turns out to be a member of her tribe. I hadn’t known either, until I’d read the book at the café an hour prior. Born Efraim Own Goldberg, his first wife had convinced him to change his name before they divorced a few years later. Even after he changed it, he continued to experience antisemitism, including in the army. His parents were children of immigrants from Russia and Poland, who ended up in Toronto, Canada, where Gehry was born. At age 18, following the end of WWII, the family moved to LA, where a vibrant art community nurtured his architectural interest, pursuit, and particular style. Gehry’s father’s love of drawing and mother’s love of music must have rubbed off on him. He claims he has always related more to artists than to architects. Whenever he feels stuck or frustrated with a project, he goes to a museum or turns to other forms of art, such as music or literature, where he finds inspiration to continue.

I finally wave goodbye to my mother and look back one last time for a final glance at the museum. I can’t seem to get enough of it. And to think that after the project was finished, Gehry fretted over his creation, thinking Oh my God, what have I done to [the people of Bilbao]? His self-deprecation and doubt surprise and please me. If Gehry can question his artistry, then I don’t feel so alone when questioning mine. At the same time, when reflecting on critics of the Guggenheim Bilbao, as well as his other works, he takes a similar view as Renzo Piano, the architect of the Centre Pompidou, took in the maelstrom of opposition to his own work in Paris. While acknowledging the subjectivity of all art forms, with respect to those who oppose his buildings Gehry suggests, “Maybe it’s not beautiful by definition in their world, but it may over time become beautiful if you live with it…Over time, if they’re any good, they become iconic and accepted and change people’s mind about what is beautiful. Or they accept it as beautiful.”

This may be the one point on which I respectfully disagree with Gehry. I’m not sure that something I find to be an eyesore will grow on me to eventually become beautiful. There are numerous buildings I’ve walked past many times in Manhattan that I found ugly and that view never changed. Just as flaws in my own homes have continued to stand out to me until I finally took leave of them. But that doesn’t mean I can’t live with them. In any case, every single work I’ve seen by Frank Gehry is beautiful to me. Particularly the Guggenheim Bilbao, a destination I finally got to tick off my bucket list.

In the end, Gehry had achieved even more than what the administrators of Bilbao in the 1990s had set out to accomplish in transforming Bilbao into an important mecca for tourists in the Basque region, attracting tourists and major retailers. Gehry’s design has also led other prestigious architects to add their own unique designs and ideals of beauty to the port city by the Pyrenees Mountains.