The Chicago Tribune arrives on Monday in its blue plastic sack, bespeckled with tiny beads of morning dew. Lydia holds the paper carefully away from the table as she coaxes it free from its clingy raincoat. She’d always found the Monday paper oddly comforting–no loud colors, no stack of ad slicks oozing out of the middle like pie filling. The Monday paper is thin, succinct, black-and-white, back-to-business. Predictable. Everything Monday mornings are supposed to be.

Lydia suspects her father felt the same way about the Monday paper, though he’d never exactly said so. She opens the Arts and Leisure section to the last page, imagines his unruly penmanship on the word jumble and the crossword puzzle. Neither feature appears in the Sunday paper, and on Mondays and Mondays only, Phil Brennan bypassed the front page and the sports section to start with Arts and Leisure.

“You must be the last person on Earth who still gets an actual paper delivered, Dad,” she’d chided him on a visit maybe two months prior, watching as he skillfully decoded “SWDARHIHAES” to “DISHWASHER”.

He’d chuckled in his good-natured way and rubbed the back of his neck with one long, calloused hand. The hand of a working man. “Yeah,” he’d admitted. “Just can’t seem to break the habit.”

She hadn’t known the half of it then. She’d stayed behind to settle his accounts, deal with the banks and the insurance companies. Turns out he’d never had a debit card; he still went to the bank and wrote checks to “Cash.”

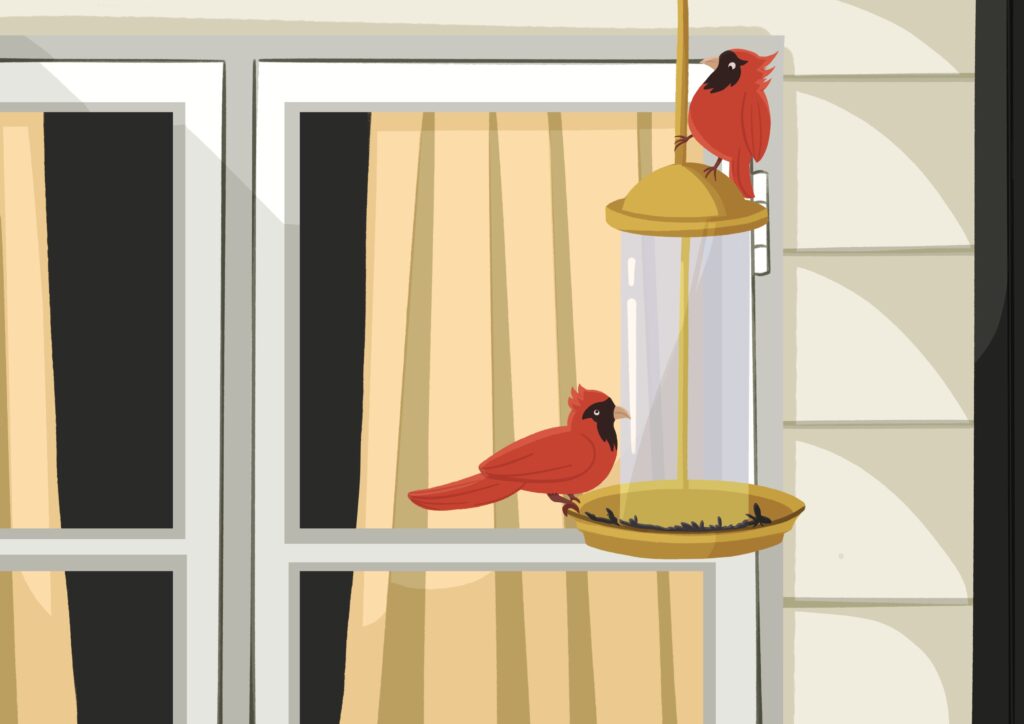

Now, a flash of red catches her eye, and Lydia looks up. The male cardinal has perched on Phil’s window birdfeeder. It watches Lydia for a moment, cocking its head side to side, then flies back five feet to the fence post. Immediately, the female cardinal swoops in and pecks through a pile of mostly empty seed shells, searching for a winner. This has been the cardinals’ routine every day since Lydia arrived two weeks ago: Lady doesn’t eat until Gentleman has deemed it safe. Surely her father had noticed this same charming pattern, sitting in this same spot with his coffee and his Tribune, but he’d never mentioned it to Lydia. He wasn’t one for telling stories.

“Buy cardinal feed,” Lydia adds to the to-do list on her phone. She looks down at the jumble, takes a deep breath, then types, “Cancel Tribune.”

*****

Phil Brennan died on a Sunday. It was a fluke 75 degree day in the usually unbearably hot month of July and, having seen this in the forecast a week prior, he’d asked Lydia to drive down from Chicago with Manny and the kids.

“We’ll have a cookout!” he’d said cheerfully. “I’ll make the burgers thin, just the way the kids like them. And I’ll make the Rice Krispie treats with the rainbow sprinkles, just for Cassie.” As usual, Lydia had protested, insisted that a cookout was too much work, that they could order takeout–and, as usual, Phil had waved those concerns away. “Nah, it’s good for me. What else does an old, retired man have to do? I’m spending way too much time staring at the idiot box.”

At 78, he hadn’t looked old. His sandy brown hair had only the tiniest hints of gray at the temples, and he stood tall and straight as an arrow. He mowed his own lawn and the lawn next door for the old widow Mrs. Bates. Nothing brought him more joy than his grandkids, Wyatt and Cassie, in whom he saw kindred spirits. Something had awakened in him when the kids were born, something mischievous and child-like that laid dormant during Lydia and her brother Sean’s formative years, when work and single-parenthood demanded a stoic Phil Brennan. The weight of the world was lifted from his shoulders, and he was free to get down on his hands and knees to play matchbox cars with Wyatt, to push Cassie on her swing, to hunt for lightning bugs and throw water balloons. Lydia, awkwardly, was cast into something of a parental role over her father, forced to set limits for a grown man who suddenly had none.

“No, Dad, they can’t take their shoes off to wade in the creek. It’s 50 degrees outside.”

“I don’t care if it’s only three blocks away, Cassie can’t get into the car without her carseat.”

“Dad! That piece of cake is bigger than his head!”

To the kids, Phil was everything. An ally, a jungle gym, a raging river of nonstop fun that Lydia was helpless to contain. Not that she minded. She could watch her father with the kids all day, drink up the happiness on all three faces. She was craving it on the day he died, driving down from the city to Bloomington with Manny to her right and the kids chirping with anticipation in the backseat. There was nothing quite like the moment when they pulled into Phil’s driveway to find him standing on the porch, waiting for the children to run screaming into his arms.

“Papa! Papa!”

“Hey! Thing 1 and Thing 2!”

They’d try to pull him into the backyard to get him to themselves, but Phil always waited until he’d kissed Lydia and shook Manny’s hand, exchanging insights about the Bears or the White Sox. Finally he’d succumb to Wyatt and Cassie’s impatient tugs and rush off with them, the first stop always the vegetable garden where Phil would pick them fresh pea pods and they’d hunt for worms and Garter snakes. Lydia and Manny followed lazily behind, enjoying the scene, feeling the parental relief of both kids being occupied and out of their hair.

But on this Sunday, when they turn the corner on to Phil’s street, they see the ambulance and fire truck. They see her brother, Sean, standing in the front yard, watching the trucks, and as they approach Lydia hopes over and over again, with a ferocity she’s not proud of, that it is Mrs. Bates in that ambulance. But once they get close enough to see the look on Sean’s face, she knows it’s her dad, and she knows that he is gone

*****

“I dreamt about him last night,” Sean says, pulling a throw blanket off the back of the couch and wrapping it around his shoulders. It’s a hot, muggy morning, but somehow Sean always wakes up freezing cold. “He was out there feeding the birds.”

She smiles faintly, then swallows hard. She’ll never watch her father feed the birds again. Since her father’s death three weeks ago, Lydia has been measuring everything in relation to Phil: the first sunset without Phil, the first Tuesday without Phil. Pouring bad milk down the sink last week had brought her to tears: He’d been gone long enough for a gallon of milk to go sour. She imagined him in the store, reaching, as always, for the fresher container in the back, probably selecting a gallon only because Wyatt and Cassie were coming. A half gallon would have been more than enough for him and Sean.

“Did he say anything?” Lydia asks her brother. She’s jealous. She’s been desperate to dream about Phil.

“No.” He’s shaking his head, and his voice is an octave lower than usual. Lydia recognizes this as his trying-not-to-cry move. Sure enough, his eyeballs are painted with tears. “I was sitting where I am now, just watching him. I kept hoping he’d look back at me, but he didn’t.”

Lydia feels a wave of affection for her older brother. She’s certain she’s never loved him more than she has these past three weeks. She remembers them approaching Phil’s coffin, clinging to one another like frightened children as they inched closer and closer for that first look. They might as well have been the same person in that moment…two souls welded together by shared devastation, by a keen and tragic focus on one man, one loss.

She sits down next to him on the couch and wishes she could think of something profound to say. Instead, “I bought a bag of the birdseed today. It’s in the garage. You need to make sure the feeder is always filled.”

He sighs and looks out the window. “Can’t they just find worms? There’s a ton in the garden.”

“Cardinals don’t eat worms,” Phil said. “They eat seeds.”

Lydia looks toward the backyard as she recalls this conversation. She was maybe 14, lounging in a deck chair reading a VC Andrews novel while her father replaced the sugar water in the hummingbird feeder. When he stretched for the hanging seed feeder, he let out an involuntary grunt of pain and rubbed his bad shoulder, worn down from years of carrying steel beams on construction sites.

“If your shoulder hurts so much, why don’t you stop feeding the birds? They’re wild. They can find their own food.”

He looked at her a moment and then shrugged, the way he always did when he sidestepped her adolescent scorn. “Once you start feeding them, you can’t stop. They’ve lost their survival skills. It would be cruel.”

Teenage Lydia rolled her eyes and looked back at her book. “Then why did you start in the first place?”

He shifted uncomfortably, then chuckled softly and rubbed the back of his neck. “Heh. Yeah. Maybe I shouldn’t have.”

Now, Sean sighs and wraps his blanket a bit tighter. “I’ll try to remember the cardinals. How are Manny and the kids doing without you?”

“I think they’re ok,” she says slowly, for she suspects that they all–even seven-year-old Cassie–are just putting on a brave face for her during their nightly video calls. She knows that Wyatt, at age nine, is the most affected by his mother’s absence. He’s a serious boy with a furrowed brow, always worried how everyone else is feeling. Sometimes it’s easy to forget that he’s still just a child, a lost little soul who just wants his mom but is determined not to show it.

“I promise we’re ok, hon,” Manny had told her the night before, folding laundry after the kids had gone to bed. “Stay as long as you need to.”

“I can’t take any unpaid days–”

“Don’t worry about that. How many hours have we wasted worrying about money? But we’re still here. We’re alive. No one knows how to survive better than social workers.”

“I just don’t want to leave any loose ends,” she said with a sigh. “I had no idea how much paperwork is involved with dying.”

“Have you talked to Sean about the house yet?”

She tucked a strand of hair behind her ear and readjusted her glasses. “Not yet.”

***

The Offices of Randall Stone & Son are in a strip mall between a 7-11 and the Hillcrest Currency Exchange. Before climbing out of her Camry, Lydia pauses for a moment to watch a large man exit the currency exchange and light a Camel under a sign that reads “Same-Day Payday Loans.” With the cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, the man pulls a wad of cash out of his jacket pocket and transfers it to his billfold, which is so well-worn and threadbare that Lydia fears it will disintegrate in his hands. But it holds, and the man stuffs it in his back pocket, takes a drag off his smoke, and starts a lumbered waddle toward the 7-11.

“Mrs. Rivera,” Randall Stone says, crossing the lobby and extending his hand. “It’s nice to meet you. I’m so sorry for your loss. Won’t you come join me in my office?”

The aesthetics of strip-mall law aren’t too different from the aesthetics of social work, Lydia notes: fluorescent lighting, dingy cubicle walls, a couple of low-maintenance plants. They pass a desk with a sign that reads “Whether You Think You Can, or Think You Can’t, You are Right” displayed next to a plastic cube with pictures of children on it. One child is holding a baseball bat, a proud smile displaying two missing front teeth; another is holding up a golden retriever puppy. As they round the corner to Stone’s office, Lydia can see one more side to the cube: a bald baby in a sweater vest sitting next to a giant wooden “1.”

“Your father was a construction worker?” Stone asks, rolling forward in his office chair. As he folds his hands Lydia notices first the gold and ruby contrast of his class ring, then the smooth, polished gleam of his manicured hands.

“A steel worker. Westerwall Steel. Thirty-six years.”

“That’s quite a tenure,” he says. “He must have been a strong man.”

A nod, she hoped, would suffice.

“I see here,” he says, tapping his knuckle on a document before him, “that you have a brother, Sean. Will he be joining us today?”

“No. Sean is not…feeling well.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. Well, everything is pretty straightforward,” he says, sliding the paperwork across the table. “Your late mother, Patricia, was listed as sole benefactor, with you and your brother listed as equal secondary beneficiaries. Everything–from his life insurance, to his savings, to his house, is to be split 50/50 between you and your brother. You are listed as the executor.”

She nods, unsurprised. “Did you review the account information I sent you?”

“I did, and it’s like you said,” he says, shuffling through the papers, then pointing to a figure. “His most valuable asset was, by far, his home.”

Home. Lydia can still remember the look on her father’s face when, after an outing, he’d usher her and Sean over the threshold and shut and lock the door behind them, his relief so palpable that she felt it in her own soul. She sees now that Phil had, with clenched fists and gritted teeth, been determined for his children to have not only normalcy, but fun, and so he planned these little outings–Six Flags, the zoo, the science museum–despite the obvious torment they brought him. “Hold your sister’s hand!” “Stay together!” “Don’t run ahead!” Lydia learned to dread these excursions, staying close to Phil and following directions carefully, her logic being that if she was extra good her father would only have Sean to worry about. And there was always plenty to worry about with Sean.

“Don’t lean so far over that edge, Sean!”

“Sean, stop climbing on that!”

“Sean, wait your turn!”

The irony was that these misbehaviors seemed to get Sean more of what he wanted.

“Yes, if you will sit here and eat it nicely, you can have a cotton candy.”

“Fine, I will get you the hat, but pick one in a bright color so at least I can spot you better in the crowd.”

She remembers leaning against her father’s chest, feeling the rhythmic rising and falling, watching Sean dismantle a blue puff of sugar with a canary-yellow Pikachu on this head. “Thank you for being such a good girl, Lydia,” he’d whispered in her ear. “You’re always my good girl.”

“If you’re in need of a real estate attorney,” Stone says now, “I can refer you to a colleague. She’s the best in the area.” He shifts in the silence that follows. “You do plan to sell?”

The presumed owner of the photo cube returns to her desk, checking her smart watch before waking up her computer screen. Lydia watches as the woman’s no-chip talons float effortlessly over the keyboard. She’s always in awe of women who aren’t slowed down by fingernails that length. She herself has never gone for a manicure, citing the cost and the loss of dexterity. But she’s always been curious.

“My brother lives in the house,” she says.

“Oh, I see,” Stone says. “Was he caring for your father?

“No. My father never required care. His death was unexpected. Heart attack.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.” He takes off his glasses and rubs them on his sleeve. “Though some feel it’s better that way.”

She listens as Stone talks about her father’s accounts, accepts each document he slides across the desk. Paperwork is comfortable and familiar, and she absorbs the minutia as she does in her own cramped cubicle in Chicago. The rhythm of paperwork is magic: As one task after another unfolds, the demons they represent fade to the background. It’s not a child who was sexually abused by their father: it’s just a SCAR form. It’s not a baby born addicted to drugs: it’s just a medical assessment report. And what she holds in her hand presently is just a life insurance policy, not a reminder that her father is cold in the ground.

“If any questions arise, don’t hesitate to give me a call,” Stone says as he sees her to the door. “And the offer stands about the real estate attorney.”

The old Camry’s engine turns over on the first try: a victory. Lydia looks up to see the man from the currency exchange waddling out of the 7-11. At least three sheets of scratch-off lottery tickets dangle from his nicotine-stained fingers.

***

“The thing is, Lyd,” Sean says, reaching for the last slice of pizza, “I’ve never lived anywhere else.”

This isn’t entirely true. After much contemplation, her father had decided Sean should “at least try” going away to college, despite Sean’s protests.

“Maybe it will ignite something in him,” she’d overheard her father telling Mrs. Bates one night. Mrs. Bates always sent them to bed too early when she babysat, and Lydia couldn’t sleep. She crept to the landing of the stairs, hiding in the blindspot that allowed her to eavesdrop on adult conversation in the living room. “Distance and independence can be good for young people.”

“Absolutely,” Mrs. Bates said. “Coddling kids never does them any good.”

“I mean, I left home at 18.”

“I left at 16.”

“It’s a perfectly normal thing.”

“The most normal thing in the world.”

“When we sell the house,” Lydia tells Sean now, “you can use your half to buy your own place.”

“Half the money will only buy half a house.”

“You can use it as a down payment.”

“Then I’ll have a mortgage. How am I supposed to pay a mortgage?”

The obvious answer, get a job, hung between them like pollen stuck in dense, August humidity. Lydia leaves it there.

“Sean, I just want what’s best for both of us. And for my family.”

He spins around, his eyes daggers. “So what, I’m just the loser uncle who’s trying to steal money from his own niece and nephew?”

“No, Sean–”

“I’m so sorry for existing, Lydia. I’m so sorry to be an inconvenience to you, and to Manny, and to your perfect little life and your perfect little family. We’re not all so lucky, you know.”

“Sean, please, let’s–”

“I suppose this is because I’m just his stepchild, and you’re the trueborn princess. I’m just the brat he was saddled with from’s Mom’s first marriage. The little jerk who’s real father didn’t want him.”

“Sean, you know Dad never thought that w–”

“Maybe it would be better for everyone if I were dead, too.” His voice catches now, and there’s a vulnerable lift to his brow. “There’s no point in me being here. I’m just a burden to everyone.”

“You are not, Sean. Please, just–”

“You think I asked for this?” Tears escape down his cheeks. “To watch my father drop dead in front of me? To find my own mother dead when I was just seven years old? Life hasn’t exactly been a bowl of cherries for me, Lyd. I’m sorry if I can’t be the model citizen you are. I’m happy for you that life has been good for you. It hasn’t been so good for me.”

The tears disarm her. She stands perfectly still, staring at a cheese bubble on the pizza. She imagines all the reasonable things she could say trapped in that bubble, fighting for air.

“Forget it. Just forget it. You’ll never understand.”

He snatches Phil’s car keys off the counter. Lydia anticipates the door slam, but still jumps when it happens.

****

She was 12 years old and folding laundry when they got the call. Snickers, their old tabby, jumped in the basket to soak in the warmth from the fresh towels. She was working around him as best she could so he could stay as long as possible, pulling towels from the sides that wouldn’t disturb him. A feline Jenga game of sorts.

Phil picked up the phone on the first ring, a habit he’d formed only since Sean went away to college. “Yes, this is Phil Brennan.”

He began to pace and rub the back of his neck. Lydia sits perfectly still, as if she can change whatever is happening on the other end of that phone by not moving a muscle. She senses movement to her left and looks out the window to see that a fat mourning dove has landed on the birdfeeder. The cardinals are nowhere to be seen.

“His roommate came home from his morning class,” the doctor tells them later that day. “He found Sean and called 911 right away. We were able to pump Sean’s stomach and get most of the aspirin out before it hit his bloodstream. He’ll make a full recovery, Mr. Brennan.”

Phil’s face has a new topography: colors, veins, and tremors that Lydia has never seen before. His eyes aren’t looking at anything in the room. “He, he didn’t want to go away. I didn’t want…I mean, I didn’t want…I thought it would be good for him. I thought maybe I was coddling him too much. It seemed a normal thing…to go to college…”

“Mr. Brennan, it’s not your fault. No one can predict these things.”

“He’s always been dramatic. Shouting, slamming doors. So when he said, ‘You’re killing me!’ I didn’t take it literally. A lot of kids are scared to leave home…”

The doctor sighs, puts a hand on Phil’s back. “We would like to admit Sean to the psych ward for a few days. He needs a full examination and a treatment plan…”

Finally they are brought in to see Sean. His arms are strapped to the bed and he is sleeping. Lydia walks close to and a little behind Phil, as if they are approaching a sleeping bear.

“Oh, Sean,” Phil says. “Oh, Sean.”

Lydia has never seen her father cry before, and she can’t bear to look now, either. She focuses on his hands, which are gripping the rail of Sean’s hospital bed as the horrible shaking and sobbing commences. If they were home, Phil would be starting dinner right now. Lydia would be setting the table, and the evening news would be on in the background. Maybe Snickers would jump up on the table, and Lydia would have to shoo him away. Regular things. Normal things. Normal people.

After that, college was never mentioned again. Phil went back to work and Lydia to school, and Sean came and went as he pleased. They never spoke of the hospital again, and Lydia never saw her father cry again. Sean diligently swallowed the prescribed pills, which never really seemed to make a difference. But he was there, and he didn’t try to leave again. This seemed enough for Phil.

“It’s not right,” Lydia overheard Mrs. Bates telling Phil one night, about two years after the hospital. The adults were having coffee in the living room, and Lydia was in her usual eavesdropping spot on the landing. “A grown man not woking, not going to school, not even helping you with the yardwork. What does he do with all his time, anyway?”

“He’s usually with a girl.”

“Nice girls?”

“Some. I don’t know. He’ll tell me that she’s wonderful, she’s the one. Then there’s a huge fight. Screaming, drama. ‘She’s crazy,’ he’ll tell me. Then a week later, there’s a new ‘wonderful’ girl.”

“Surely he must have some other interests…”

“He watches TV and reads spy novels. Sometimes he tells me he’s writing a novel of his own, but then if I ask him how it’s going, he gets angry. Says I’m pressuring him, that I’m calling him a loser.”

“Hmph!” Mrs. Bates said. “I still haven’t heard a reason why he can’t get a job. You ought to light a match under that boy.”

Lydia couldn’t see Phil from her hiding spot, but she imagined him hanging his head and rubbing the back of his neck. She knows when it comes to Sean, Phil Brennan has nothing left but fear.

“Tough love is for people who haven’t been through what I’ve been through.”

****

Sean shuffles into the kitchen the next morning and smiles at Lydia as if nothing has happened. “Morning, Lyd.”

Lydia is used to this. No matter how bad Sean’s blow-ups are, there’s never a follow-up discussion, and certainly never an apology. They just move on as if nothing happened.

“I was thinking,” he says, turning the electric kettle on for his instant coffee. “Maybe we could do a movie marathon today. Like when we were kids, remember? We’d build a fort in front of the TV, make insane amounts of popcorn, then take turns picking movies all day. Dad didn’t like the popcorn-and-Sprite diet, but he was probably so happy to have us out of his hair all day that he let it slide.”

Lydia can’t help but smile. “You’d get annoyed because I chose Annie every time it was my turn.”

He throws his head back and laughs as he picks up the bubbling kettle. “That’s right! I forgot about that. Well, Lyd, I’ll tell you what. You can pick Annie as many times as you want today. When it’s my turn, though, I’m thinking Robocop. And maybe Clue. Oh! And Goonies!”

Lydia takes a deep breath, then stands up and pushes in her chair. “That sounds fun, Sean, but I can’t. I’m heading back today.”

“What?” he says, putting his coffee down. “Already? I feel like you just got here!”

“I wish I could stay longer, but I’m out of vacation and bereavement time. Any more time off would have to be unpaid, and we can’t afford that.”

“Man,” he says, running his fingers through his tousled hair. He looks around the place as if he’s suddenly someplace completely foreign. “Already.”

“I’ll be back two weekends from now with Manny and the kids.”

This brightens his face a little. “Oh, great. Maybe we can have the movie marathon with the kids. I think Wyatt’s old enough for Robocop, now. And I’ve been a straight up terrible uncle for not introducing him to the Indiana Jones franchise yet.”

“I’m sure he would love that.” She clears her throat. “I’m going to make an appointment with a real estate agent, Sean. I hope that you’ll come with me.”

He looks lost for a moment as he comes back from the movie catalog he’s been building in his head. “Wait–what?”

“I’m going to sell the house.”

“We talked about this yesterday, Lyd.”

“I tried to talk to you about it, yes.”

“This is my home, Lyd. You’re going to kick me out? Evict your own brother? Who says this is only your decision, anyway?”

“Dad did,” she says. “He made me executor.”

“So everything is your way. Everything’s for you. Nothing’s for me. I’m just homeless. Kicked out of my own home by my own sister.”

“You get half of the money from the sale of the house. And we can go through Dad’s things and decide who gets what.”

“Oh and by ‘we’ you mean ‘you.’ Miss Executor.”

“I want everything to be equal, Sean. I want everything to be fair.”

“This is just typical. Typical! I’m just the burden. I’m just the problem. You and Dad always wanted rid of me. You both wished I’d died in that hospital. And all these years, you were both hoping I’d just go ahead and finish the job. You still want that. You think if you kick me out, I’ll finish the job and you’ll get everything.”

Her stomach is in her feet. She imagines she is in the fort with Sean, under a fleece ceiling with the soft glow of the old Christmas lights they’d wrapped around their Saturday-afternoon cocoon. Sean is mouthing along, dramatically, to Corey Feldman’s impassioned wishing well speech. “This one here was my dream. My wish! And it didn’t come true…” She is giggling uncontrollably in her Spongebob pajamas, never happier than when she had this version of her big brother all to herself.

Now, she looks through the kitchen window to see that both Lady and Gentleman cardinal are perched on the birdfeeder, picking through what are now all empty seed shells. They look around the yard and finally toward the house, unsure of what to do next.

“I love you, Sean,” she says, strapping her purse over her shoulder. It feels lighter than usual. As she walks to her car, she instinctively looks for the Tribune in the driveway, but it isn’t there.