The summer of 2018 has thrown up seemingly endless good sources of what has increasingly been termed “climate anxiety”. From the wildfires in British Columbia to the floods in Kerala, confirmations of what in earlier times would have been termed a biblical judgement for humanity’s sins against that which it did not create and yet depends upon for life are close at hand. It is little wonder, in such a context and with political action to halt or reverse the frequency of these events either inadequate or actively moving in the wrong direction, that more and more writers on environmental issues have begun speaking to an actively existential dread. What if, they say, a back-of-the-mind faith that policymakers would, ultimately, “get it together” on climate change was misplaced? What if, indeed, a large amount of the currently populated spaces in the world become uninhabitable within our lifetimes? What, in other words, does the world look like after the cataclysm?

We do have some existing models through which to understand this question, from both history and popular culture. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that that 2015 revival of the famed Mad Max franchise was framed around control of scarce water resources and smuggled an eco-feminist message beneath its action film trappings. Originally having been conceived amidst another set of existential anxieties, namely, nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, that franchise and its numerous imitators drew inspiration from images of post-bombing Hiroshima to inform its vision of life after the end. The brave, or foolish, or foolishly brave, souls who have ventured into Chernobyl in the wake of its nuclear disaster have returned similarly arresting images of a landscape still, silent and drained of the warmth of human life. When imagining the world in the wake of climate apocalypse, I suspect it is visions like these that bring on the anxiety so many are speaking to.

Of course, the problem with cross-applying any of these scenarios to a global climate tipping point is that they were localized to particular areas and based on a fundamentally different set of environmental impacts. The problem with the climate-caused apocalypses, plural because a singular cause will be experienced differently in different areas, comes both in our eternal inability to predict the future wholly accurately and in the fact that the world has seldom experienced chains of disasters, of end times, in rapid succession. Cleaning up and assisting the impacted after a singularly devastating event in one place is enough of a challenge, let alone trying to do it for five or six or seven which increase in severity each year. It is easy to imagine a situation where such eventualities lead to increased indifference to the suffering of others, where those with resources retreat ever more behind moats and high walls and let the rest of the world fester and rot in the aftermath. It is not hard to imagine such a scenario coming to pass, one would simply need to extrapolate the lives of elites in countries such as Haiti or El Salvador to a global scale. This world of guards, gates and guns may not fit precisely fit the images of apocalypse we imbibe from movies and news, but they are an end to the kind of world most people would want to live in, just the same.

But what if the end times did occur, and people simply picked up after, acting as if they did not? Or, at least, that the end was not the end of all things?

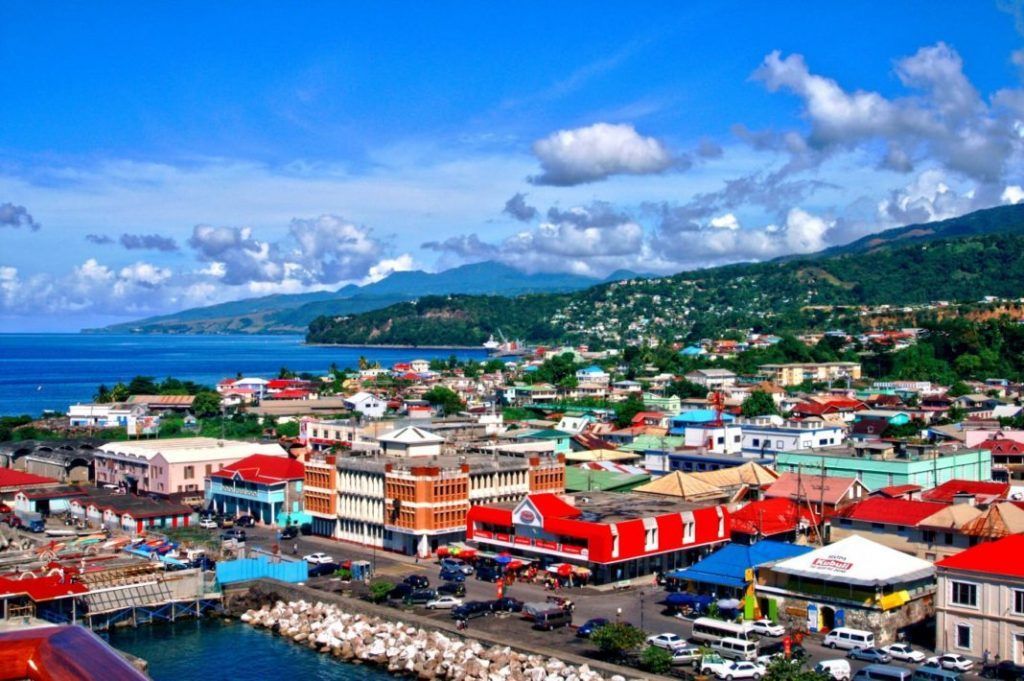

Perhaps, if we look to the small Caribbean nation of Dominica, a nation which faced down the climate-induced apocalypse and lived to tell, a vision of what this world looks like can be seen.

Storms, Travails

Hurricane Maria struck Dominica in September of 2017, before more famously going on to devastate Puerto Rico afterwards, and wrought a form of destruction that is nearly impossible to understand if not experienced firsthand. Ninety percent of the island’s buildings were damaged in severe ways, with many simply gone, their component parts tossed like matchsticks across the terrain. The famed greenery of the island, which defies regional stereotypes by being mountainous, having few beaches and not much sand, is now pock-marked with centuries-old trees simply snapped in half, while others remain stripped of leaves and bark. In economic terms, the damage was estimated to total about 200% of the nation of approximately 80,000’s annual GDP. Many businesses have not yet reopened, and some, including an overseas medical school campus, have simply packed up and left entirely. Piles of scrap metal, twisted blocks of rebar and concrete and rusted hulls of cars lie near the side of the sole operational highway in the country in all the communities it winds through. Restored buildings, the end products of the inescapable soundtrack of tapping hammers and whirring sawblades, sit next to roofless half-structures, whose ostensible owners have seemingly left for greener pastures, leaving that lot behind as a testament that they were, indeed, here.

With that said, there is a normality to things in Dominica that at first can seem eerie to an outsider, almost as if people are play-acting their old lives out amidst the rubble because anything else would invite too much pain. The mini-buses, vans retrofitted with extra seats in the aisle space, still wheeze and run along their routes. There are still women crouched under Maggi-branded umbrellas selling produce near the waterfront (though they will apologise for it being mostly root vegetables). There is also, thankfully, little of the high-walls and razor wire shtick that often substitutes for civil fabric in places of sharp inequality. Crime is generally low in the country and those who do have money don’t appear to be at great pains to show it off. The most ostentatious houses look like simply average North American suburban tract homes, albeit built very high up into the mountain air. Perhaps this state of affairs comes down to the fact that, unlike most of its neighbours, Dominica never developed a mass tourism industry and the attendant inequalities that brings. For all the bits of wreckage lying around, the air can most often smell of fresh paint, of unlived freedom, of the possibility of being happy to grind it out in the sweat and grit and dirt with everyone else.

It is also not the case that, however much they may have suffered, Dominica’s citizenry are sallow or resigned to their country being only a bug light for natural disasters. Rather, there is a sense that if self and family could survive Maria, they could survive anything and that the future can only be brighter. The ability to look forward, past the horizon line, to the time when you can the tarp off your house and have a real roof again may seem like a small comfort, but it is a remarkable North Star in the right circumstances. One of the most popular songs in the country, played regularly before morning news announcements on the radio, is a cheery, darkly comic reggae number which recounts all the things that “Maria took” from one man’s life. It starts with shirts, pants, that sort of thing, before getting considerably more grave and listing the man’s mother and wife being taken away. It generally gets a couple solid guffaws in the bus.

Boots and Resistance

If I had any advice for someone going anywhere, but especially for travelling into the post-apocalypse it would be this: wear good boots. By this I mean a sturdy pair that can bring you across fallen trees branches and power lines, whose soles will stand up to broken glass and jagged stones, whose sides can breathe easily in the heat but will also protect from soaking, sudden rains. This may seem facile, but in hiking through the trails of Dominica, with their narrow cliff edges worn away by wind and rain, their uphill climbs made more perilous by the exposed tangles of uprooted trees. It would not be an exaggeration to say that, without those boots what were able to grip tight into the soil, I likely would have fallen into a jungle thicket and, at the very least, been unable to type these words. What was remarkable to notice, though, was that most of the people I would go on those hikes with were able to tackle those same dangers while wearing worn-down sneakers or, remarkably, sandals. Those boots were a kind of protection mechanism for me, the outsider, which I needed to face post-Maria Dominica in a way those intimately familiar with it did not.

Similarly, the very idea of “climate anxiety” itself can be seen as a kind of privilege for those who live outside of the immediate blast zone of the most impactful manifestations of these changes. After all, the ability to be anxious about something is fundamentally based in the fact that one can see it coming. Even if powerless to stop it, preparations can be made, psychological barriers can be set up to drown out the impending devastation. For those with wealth or other kinds of social cache, the worst effects can be avoided or carefully mitigated if and when the devastation arrives. For the people who experience the brunt of the various storms head on, though, there is little time to be anxious. Certainly, whatever foresight is available cannot be spent on matters of rumination, but rather on physical preparations, the boarding up of doors and windows, the stockpiling of canned goods and batteries. This is a lesson that the people of Dominica have particularly taken to heart. When news came in July of a potential hurricane, the shelves of most stores were absent of crackers and baked beans for a time. All around, people were asking if I had enough water to last a week if the taps shut off and my landlord assured me that I could bunker down with his family in a personal storm cellar (that had survived Maria fully intact!) if I wanted. In the event, the hurricane was quickly downgraded as it approached to a tropical storm, then to a tropical wave. When it did it, it was essentially a heavy rain storm, which did flood a nearby riverbank, but otherwise passed like many others the nations had seen before and were a normal part of doing business. Whatever divine force you may believe in was, seemingly, not going to be quite that cruel to the Dominica and its people. But those store shelves were a sign of a people who had seen the end once before and needed only the suggestion of a second ending to prepare themselves. This is a manifestation of anxiety truly felt, but more than anxiety, it is a sense of knowing that the worst can and does happen, rather than simply predicting that it is likely to.

Dominica received its current name from Christopher Columbus, who named it after the day upon which he and his crew spotted the island from their ship (in English, Sunday). The opening up the “New World” to European conquest which followed from Columbus’ initial spotting of this and many other islands in the Caribbean could, in itself, be seen as a kind of apocalypse from the perspective of the Indigenous populations there. If it is defined as an event which renders that which came before impossible to return to, and which cuts through the essential fabric of a society, building something else by force in its wake. With that said, the resistance to this force in Dominica was particularly strong amongst the native Kalinago people (the old European term for these people, “Caribs”, is where name for the region comes from). Despite efforts by Spanish, French and finally English colonial masters to turn the island into a planation economy, with the importation of tens of thousands of slaves primarily from West Africa, whose descendants now make up the bulk of the population this project was never as successful as in other islands of the region. This was because the Kalinago, later joined by communities of escaped slaves, took to the mountains where the Europeans were both unfamiliar with the territory and died easily from tropical diseases. From there, they built and maintained communities which fought off, often fiercely attempts to subdue them to colonial will. Today, Dominica retains a significant Kalinago population, who have won a degree of independence from the central government in a designated territory in the southeast of the island

In this sense, there is a full circle to what Dominica has experienced from the arrival of Columbus to Hurricane Maria. Always marginal in the designs of global powers, it nevertheless seems destined to suffer some of the worst consequences of their actions and inactions. Dominica won its independence from the United Kingdom in 1978, later than many of its fellow islands, despite its comparably negligible economic contribution to the British Empire. Though I am not sure of why, exactly, this was, perhaps the relative inability of the island’s populace to come fully under the imperial boot heel was incentive to hold on long past the point of letting go of the brighter jewels in the crown.

Resistance is a powerful force, perhaps most so when it can seem futile in the immediate circumstances. The force of Hurricane Maria was a gun aimed at the temple of Dominica and its people, loaded with the bullets of the industrialized world whose benefits; the country itself had only ever experienced partially, unevenly and belatedly. A lesser country, a lesser people may simply have packed up, dispersed its population throughout the regional islands and left itself as a monument to the world’s indifference in the face of catastrophe. However, Dominica did not do that, rather, person-by-person, brick-by-brick, nail-by-nail, decided to rebuild themselves into a monument to something more powerful. Faced with the prospect of fading into the night of human history, Dominica simply said no. They said no as the Kalinago people who had lived in its mountains for thousands of years prior to Columbus’ arrival did, when faced with the prospect of total annihilation. They said no as the enslaved people who escaped into the mountains and formed the basis of an independent political identity that would take over a century to be realized did. And perhaps they said no as all of us who are interested in continuing to live together on this planet will have to.