Alexis St. Martin sat on a hospital bed and watched the falling snow coat a large ship docked in the Anacostia River. He wished he could put his woolen shirt back on, but Dr. William Beaumont probed at a hole in his stomach with a metal tool.

“See how the skin grows around the wound rather than over it?” the doctor said to half a dozen Naval hospital physicians based in Washington, D.C., who were crowded around St. Martin. “The wound healed incorrectly, and the resulting fistula allows us to witness human digestion in real-time.”

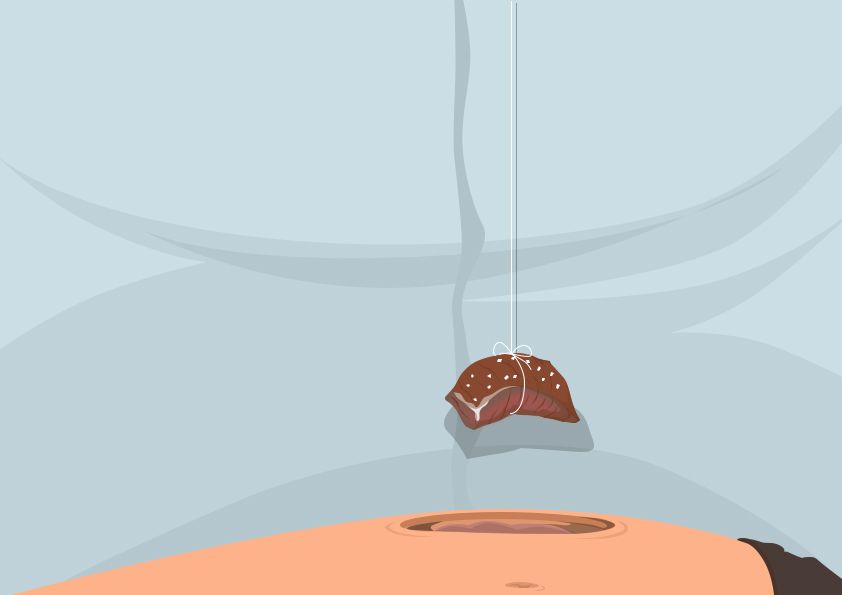

Dr. Beaumont tapped St. Martin’s shoulder twice, and the French Canadian lay down on the bed. The other physicians blocked St. Martin’s view of the doctor, but it didn’t matter. He knew that the doctor was selecting a piece of salted meat and tying a piece of string around it.

“What are your plans for Christmas?” the tallest doctor in the group asked Dr. Beaumont.

“No plans at the moment,” replied Dr. Beaumont, returning with the dangling piece of beef. He swatted at a fly circling around the food. “I’ll probably just have dinner at the inn.”

“Nonsense, William.” The doctor clapped his new friend on the back. “You’ll join me and my family tomorrow for church and a luncheon.”

“All right, all right,” laughed Dr. Beaumont. “Now watch this, boys.” He dropped the food into the fistula. The beef disappeared into St. Martin’s stomach, and the physicians leaned close to see where it went. Years ago, St. Martin and his wife had tried this as well, him holding up a mirror to his belly and his wife dropping a biscuit into his wound. The hole was cavernous, though, as the doctors soon discovered. One of them grabbed a candlestick from the desk and nearly singed St. Martin’s stomach hair by holding the flame so close to the fissure. Dr. Beaumont gently pushed the doctor’s arm away.

“How did this occur?” said the physician, wiping wax from his hand.

“St. Martin, why don’t you tell them?” said Dr. Beaumont. He tugged the string up and down as if it was a fishing line.

“He saved my life,” said St. Martin, enunciating each word so they could understand through his thick French-Canadian accent. The group of naval doctors looked him in the eye for the first time, and their faces registered surprise like he was a character out of a fairytale rather than a human just like them. He was used to this. He paused before delivering his next line. “He took a bullet for me.”

“You mean I took a bullet from you,” Dr. Beaumont answered with a laugh. His patient steeled his face to refrain from making an expression that might break the doctor’s spell over his audience. St. Martin spoke English fine. Though he’d grown up in Quebec, he’d spent enough time on American trading boats in his younger years to have a solid grasp of the language.

“It was a fortunate circumstance, actually,” Dr. Beaumont continued. “Alexis here got himself in a bit of trouble after misfiring a gun.”

St. Martin hadn’t been the one misfiring the gun, but he held his tongue. His part was over, save for the gastric juices that were consuming the beef the doctor had lowered into his belly.

He looked at the wooden planks on the ceiling rather than the circle of faces that stared down at him from above. Just before the accident and his chance meeting the doctor, he had secured a spot on an American schooner bringing furs from the backcountry around the Michigan territory. He’d finally been making real money, enough to support his growing family. Then one June afternoon, nearly a decade ago now, he was moored in the harbor at Fort Michilimackinac, out on Lake Huron. Ships filled the harbor, and with them plenty of sailors. He went into the mercantile to pick up a bottle of whiskey, and one of the deckhands from another crew stood a few feet away, admiring a shotgun. They told him the gun misfired, though he doesn’t remember anything between watching the bottle drop out of his hand and shattering on the wood floor and waking up in Dr. Beaumont’s house with a hole in his stomach.

“Everyone said he was as good as dead. But my wife and I took care of him and helped him regain his strength. Only the wound didn’t heal correctly.” Dr. Beaumont pulled the string out of St. Martin, which drew the eyes of the doctors. They stared at the piece of meat, which was covered in a thin layer of stomach slime.

“Instead, the skin just grew around the gap, leaving a permanent window into his digestive system. If he didn’t eat lying down, gastric juices would pour out of the hole an hour or so after his meal.” The captive audience murmured to each other, still looking at St. Martin’s belly. “I tried putting food directly into the wound, but I had the same problem as you did. I couldn’t see what happened to it. That’s why I created this contraption.” Dr. Beaumont plucked the cord with his free hand, as if it was a fiddle string. “I knew at that moment that fortune had delivered me the perfect test case.”

And fortune had delivered St. Martin a job. He could no longer work on a ship in his condition, but Dr. Beaumont had offered him a modest wage to travel with him to hospitals and city halls around the country.

He adjusted his head on the pillow so he could see out the window again. He wondered if Montreal had this much snow, and imagined stoking a fire to welcome his children in from a day spent making snowmen. He pictured helping to set the table while his wife cut the bûche de Noël, something they saved for each Christmas. It seemed to St. Martin that they always had extra space on the table for food and never enough room around it for the children.

“By the time we’re done here, there will be nothing left at the end of this rope,” said Dr. Beaumont with a tea-stained smile. This continued for several hours, as the doctor explained the different stages of the digestive process by pulling up the string at intervals and revealing the breakdown of the sludgy beef. St. Martin tried to sleep, warming at the thought of the drink he’d have later that night with the money from today’s demonstration.

“We’re done here,” said Dr. Beaumont, wrapping his scarf around his neck. “I’ll see you for dinner this evening.” The doctor placed a few coins on the bed next to his patient, then put on his hat and left the room.

St. Martin found his shirt in the corner of the room, then donned his overcoat and worked his way through the hospital hallways to the street.

It was a long walk back to the inn, and St. Martin took his time, stopping in a general store to warm up. A glass container stuffed with peppermint sticks sat on the counter. St. Martin opened the jar and took one out, twisting it in his hand, following the red stripes as they swirled toward the bottom of the rod.

“You want to purchase that? Or you just want to get your fingerprints all over it?” said the shopkeeper from his seat near the window.

St. Martin placed the stick on the counter and then reached in to grab six more. He placed a few of the coins he’d pocketed from the day’s demonstration next to the candy. He knew he should just send the money home, that it was a waste to ship peppermint that would break in transit. Still, he made the purchase. His wife would know how to make something out of the crushed candy.

The shopkeeper stood up, and the stool creaked as if grateful to be freed from the weight of the man. He put the coins into the pocket of his apron, then wrapped up the candy in brown paper. St. Martin tucked the parcel into his coat and stepped back out into the afternoon.

The post office near his boarding house was still open when he arrived, and St. Martin ducked inside to send off his present. The clock tower atop the building rang out with five chimes, and St. Martin wondered if his family were at Mass or if a snowstorm had kept them home.

St. Martin and Dr. Beaumont sat in silence alongside others in Washington, D.C., who had nothing else to do on Christmas Eve.

The doctor finished his supper silently. As St. Martin put another piece of pork loin in his mouth, Dr. Beaumont picked up his napkin, wiped his lips, and stood up.

“Staying?” The doctor had asked St. Martin the same question each night for the past week when, having finished his steak and his glass of ale, he slid out of his chair.

St. Martin held up his half-finished drink.

“Go to bed once you finish that,” ordered the doctor. “We have another busy week coming up after the holiday.”

St. Martin nodded. The doctor didn’t see. He’d already started for the door.

“Joyeux Noël,” St. Martin said under his breath. He touched the hole into his stomach through his tunic. Without the doctor, he would never have had another midnight mass with his family, another slice of bûche de Noël.

The crowd at the tavern continued to thin out. The men crowded around the small table next to him got progressively louder as they made their way through rounds of drinks. St. Martin deciphered a bit of their debate about the merits of Andrew Jackson versus John Quincy Adams, then moved to the bar to have enough space to think.

“Another?” The bartender removed the stopper from the glass bottle of whiskey. His was a new face, different from the man who’d waited on him each night since he’d arrived in Washington a week ago. If he spent the remainder of his allowance from Dr. Beaumont at the bar, what of it? St. Martin tipped his glass back, letting the last drops of the brown liquor slide down his throat, then slid it across the bar.

One of the debaters called the bartender. “Henri! Another round, please.”

The bartender put the whiskey bottle back on the bar and rushed to get the man in the brown corduroy suit, his drinks. He laid several sprigs of mint on the bar, tearing the leaves from the stem with his leathery hands. The scent of the herbs butted up against the smell of pipe tobacco, the fresh mint out of place in the old bar.

St. Martin looked around. Besides the table he’d walked away from, he was the only patron in the tavern.

He stood up and placed the last of his pay from the day onto the bar. If he didn’t lie down soon, the whiskey would tumble out of his stomach. But instead of going up the tavern stairs and to his room at the inn, he stepped out into the evening, letting snowflakes fall onto his overcoat. He walked east, leaving footprints on the sidewalk that would soon be erased by more snow.

When he crossed the street, he could see the back of the White House. It was blanketed in greenery and candles and snow, and St. Martin could hear the faint sound of music coming from one of the ballrooms. It didn’t hold up against the small boughs of holly he knew were decorating the mantle at his home in Montreal, or the chorus of his children’s laughter as they chased each other around the home.

Under his coat, fluid oozed out of his wound, and he felt a wet spot forming on his tunic. He turned around, marching through the night toward the boarding house room the doctor had procured for him.