‘Are we there yet?’ Madison asks.

‘Five minutes, Maddy,’ her father, Gerald, replies.

‘But you’ve been saying that for three days!’ Timothy chimes in.

‘I know, Timmy.’ Gerald glances at his son in the rear view mirror, tilting his chin up so they can lock eyes. ‘But the panels aren’t holding as much charge as I’d hoped.’

‘I’m bored of being in the car!’ Madison whines.

‘Now, Maddy,’ their mother, Claire, chides, half-twisting around. ‘Don’t be petulant, darling. We’ve all been cooped up in the car, not just you.’

‘What does petulant mean?’ Timothy asks.

‘It means childishly sulky or bad-tempered,’ his younger sister recites.

‘It means you’re being a grumpstick!’ Gerald laughs in the encouraging way parents with remaining effort reserves do, and shifts his gaze in the mirror across to his daughter. ‘No grouchbags allowed on this road trip!’

Madison folds her arms and huffs. ‘I’m not a stick! Or a bag!’

‘Oh, no?’ Claire asks. ‘What are you then?’

‘I’m a little girl. I like dolls, but I also like cars, and that’s ok because girls are allowed to like cars the same as boys. I don’t like wearing pink, and that’s ok as well. But I don’t like blue either. I like wearing green.’ To emphasise her point, Madison uncrosses her arms and plucks the front of her lime green t-shirt. She nods once, as if to reaffirm her statement. ‘But I don’t like this car. This car has sucky range. Five hours full solar-charging during peak daylight hours barely yields 300 miles. And it smells.’

Gerald looks at her again, switching his gaze between his daughter and the near-abandoned, weed-lined motorway. ‘Sucky?’ he says, unable to keep the grin from his voice.

Madison nods once again, this time with more finality. ‘Sucky.’ But she can’t help but smirk impishly.

‘This is a very old car,’ Gerald says, his voice deliberately low and slow and serious, and his face absolutely straight. ‘We’re lucky to get what we do out of it.’

Madison considers this for a moment, then nods again. ‘Quality engineering,’ she agrees.

‘Tell you why else we’re lucky,’ Claire says. ‘It’s such an old car we can still listen to music offline!’

‘Yes!’ Madison’s older brother shouts. ‘Play the road trip musics!’

‘It’s called an album, sweetheart,’ Claire reminds him.

‘Yes! The road album trip!’

‘I’m sorry to be a Gruffalo, Sport,’ Gerald says, ‘but I don’t think we have enough juice for music and driving.’

‘Awww!’ Timothy cries.

His younger sister shakes her head slowly, holding their father’s gaze in the rear view mirror as she does so. ‘Sucky range.’ But, again, she can’t keep from grinning. ‘So sucky.’

Less than an hour later, the four of them are lying, sitting, standing, and pacing the motorway’s hard shoulder. After the car whined down into power failure, Gerald coasted to the left-hand side of the road; Madison helped her father lay out the solar panels while Claire scooted Timothy off into the trees lining the road, sliding the extras out of the boot and laying them at the optimal 43°. And now the five-hour wait till full charge.

‘I’m hot,’ Timothy whinges from the ground.

‘I know, Sweetheart,’ his mother says, squeezing his shoulder.

From where Gerald is pacing, brown leather brogues scraping the gritty tarmac, his shadow glides back and forth over his son and wife. He rubs his eyes, aching from so many hours driving, and is grateful that he doesn’t really need to be that alert to dodge stationary cars. His daughter stands perfectly still in the middle of the three-lane carriageway, staring at the horizon in the distance, at all the miles they have yet to cover.

Catatonic cars and buses squat around her. Above, red kites circle silently, wings stretched wide, forked tails twitching. Other than Gerald’s scuffing footsteps and a small wind growing stronger, there are only little, unidentifiable, natural sounds.

‘People,’ Madison says suddenly, from the middle of the motorway. ‘There are people coming.’

Timothy and Claire glance up.

Gerald stops pacing and strides over to his daughter. ‘Where?’

‘Three miles, but they’re moving slowly – it’ll be over an hour before they reach us.’

‘We could be on the move again by then,’ Gerald muses aloud. ‘Only a partial charge, but it should be enough to get us past them.’

But Madison shakes her head and points to their left. Her father follows the direction of her outstretched arm with his eyes, and immediately sees the problem. Grey clouds are swarming towards them on the strengthening wind, blocking out the sun.

‘Fuck,’ he whispers, so quietly he barely even hears the word himself.

Madison tut tuts playfully. ‘No peevishpants on this road trip, thank you very much.’

They are seventeen people in total. The group is divided into two roughly equally – eight captors and nine captives.

The captors are made up of seven men and two women, all in their thirties or forties. They wear ragtag military uniforms, mismatched desert and woodland camouflage patterns. One of the men cradles a rifle, not old, but rusty. The remainder sport bats and crowbars, or rest their hands on knives strapped to their belts with makeshift masking tape holsters.

The captives are all young women. At least three of them still teenagers. They stagger along in a central column, wrists bound by a daisy chain of thick, black rope. Their clothes are uniformly soiled and torn, draped over their bones, ragged skirts and shirts hanging to bare feet. Their faces are young, but worn.

When the group sees the family, from a distance at first, huddled together beside their charging car, they approach. The father’s pressed red, plaid shirt; the wife’s airy, purple sundress; the son’s new, blue polo shirt; the daughter’s lime green t-shirt. The nine glance at each other, grin, and move as one single creature, its core a writhing mass of pain and desire. They fan out as they draw closer, strafing with the semi-knowledgeable ease and stiffness that comes from many years spent sitting, playing first-person shooter console games.

Gerald and Claire pull Timothy and Madison closer to them, forearms snaked protectively over their shoulders. The next thing that hits them is the smell; they think it’s the captive young women, having not been given the opportunity to wash at all, but Madison knows it isn’t. It’s the smell of unwashed bodies, yes. But, more than that, it’s the smell of rot. And not just ordinary rot – foot rot or crotch rot, festering beneath months of sweat and grime and bacterial infections. This smells infinitely worse. If she were to name it, and name it she feels she must, she would call it soul rot – though she knows even the very concept is ridiculous.

The stinking, decaying men and women draw up in a loose horseshoe formation around the small family of four and their little solar powered vehicle. The grins reveal teeth like grubby wooden pegs. The one with the rifle appears emboldened by the rusty metal sliding across his greasy palms, and draws closer than the rest. Behind him, two others, one man and one woman, produce a length of dirty, black rope from a canvas rucksack, as if they were the world’s only remaining magicians, and had long since lost their desire to awe their audience.

The man with the rifle grins wider, though his skin is so black with muck, and his teeth so brown and crooked, that it looks like a grimace. He holds Gerald’s gaze and draws breath to speak.

But, before he can, he glances down at the children, first at Timothy, then at the younger, smaller Madison, and his breath whistles out tunelessly between the pegs of his teeth, like harsh, cold wind eroding rock on a gaunt mountainside.

Timothy hides his face in his mother’s hands, but Madison smiles at the man, and her smile is as far from a grimace it is possible to be – open and friendly and comfortable.

The man shifts his weight, suddenly awkward, and glances back up at Gerald and Claire. The rifle clacks in his arms as he changes position, and the others in the horseshoe sense his hesitation. He clears his throat.

‘You folks need anything?’ he asks, his voice reedy.

Gerald coughs, his throat feeling dry and scratchy, but he sounds miraculously calm. ‘Just the sun to come out again so we can get a solid charge.’

The man nods, holding Gerald’s gaze more purposefully than he had before, though Madison is still beaming at him, willing him to look down at her again. ‘Yep. This wind should help you out. Imagine it’ll clear up pretty soon.’

The horseshoe widens, and the rope slinks back into the canvas rucksack.

‘Well…’ the man continues, backing away without turning, eyes still locked on Gerald, ‘you folks have a good day now.’

Madison makes a satisfied, ‘Hmm’ sound in her throat at the man’s words; he winces and it’s as if she’s pleased that, in being thrown off balance, he hadn’t known what to do other than revert to cliché film lines from Before.

‘Thank you,’ Gerald says, more confidently. ‘You too.’

‘The women will stay with us,’ Madison says, and the man with the rifle freezes.

‘The women…’ he repeats, stupidly.

Madison nods firmly, with the same finality she had had when she’d decided their car was sucky. ‘I’d like more company.’ Then she points to one of the catatonic buses. ‘That still has fuel, and the keys are under the mat. They can follow us. There’s a petrol station fourteen miles ahead with enough good fuel they can siphon.’

The man cradling the rusty rifle – which looks suddenly very much like a plastic toy – stares down the long stretch of motorway, as if he will be able to see the fuel station she is talking about.

‘I don’t–’

‘I do.’ Madison takes a single step forward, and her smile is gone. ‘I do. Very much. Or your day is going to turn sucky. Very sucky.’

The man nods hurriedly, eyes seeming to rattle. His gaze flits across the others in the now ragged horseshoe.

Madison notes the muscles sliding beneath his skin, shifting micro-expressions that reveal his intentions before they’ve even fully formed – like an amateur chess player, she thinks, though she knows he wouldn’t recognise a Queen from a Bishop. By the time he’s caught up with his own next move, the muzzle of his rifle inching towards Madison’s chest, she’s stepped forward again, covering the remaining distance between them in less than half a second.

Her hands flit over and around his cradled rifle in a blur of movement.

‘Gah!’ He stumbles back in shock, but regains his footing and aims the rifle down at Madison’s face.

She grins again, spreading her hands. She is holding the rifle’s magazine, a single gleaming round, and the gas plug, cylinder and piston.

He gapes at her hands for a moment, then down at the rifle. Top cover open. Cocking handle racked back.

‘You could use it as a club?’ Madison suggests, scattering her spoils in different directions across the motorway, flinging crucial components through the now enormous gaps in the horseshoe. The weighty magazine travels a hundred metres before clanging into the side of an abandoned truck, the sound reverberating back down the motorway at them like the distant shout of an angry giant.

The man doesn’t try to use the rifle as a club.

He staggers back a few more paces, turns, and runs. His underlings follow suit.

Madison smiles more broadly and waves them off, flapping her hand wildly and straining on her tiptoes until they are out of view. Then she looks the bedraggled women over, bound and threadbare, faces both hopeful and terrified, and turns back to her family.

‘That went well,’ she says. Above, the sun breaks through the clouds and she beams. ‘By the time we’ve got the bus turned around, the car’ll have plenty of charge to make the petrol station.’

Gerald nods. ‘Good job, Pumpkin.’ He sweeps her up into his arms and kisses her cheek, and she squeals.

‘Will you play the music this time?’ she asks.

‘Absolutely.’

She nods, as if this were the only right answer. ‘I might just have a quick rest while you swing the bus around.’

Gerald places her back on the tarmac. ‘Of course, Sweetheart. How long do you need?’

Madison smiles impishly.

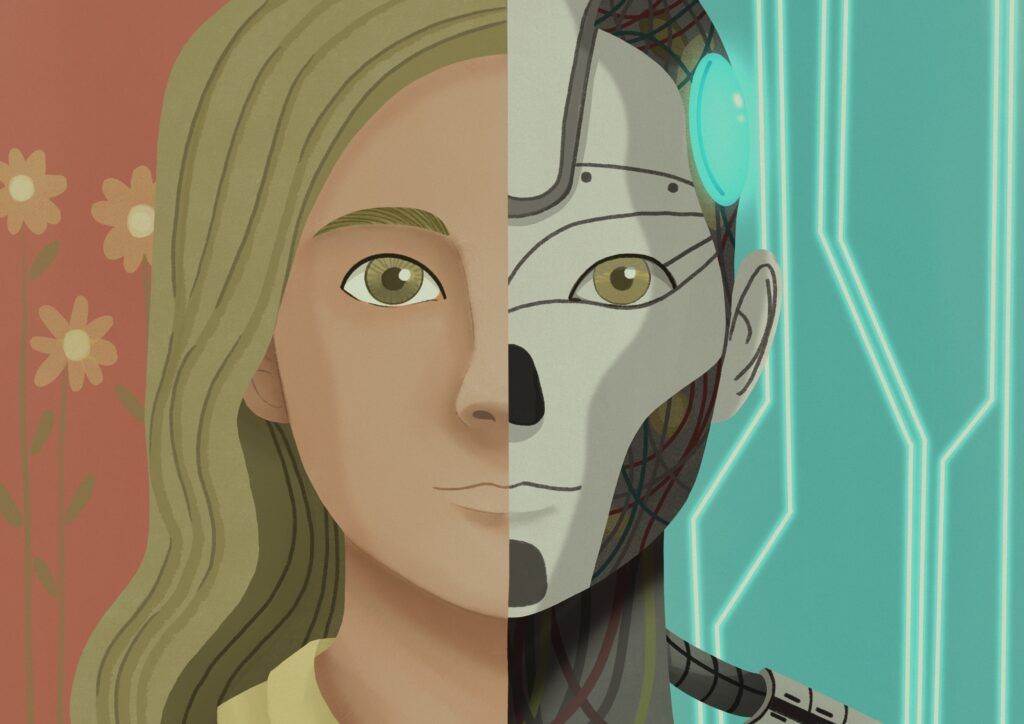

‘Five minutes,’ she says, peeling the skin from the nape of her neck and unlatching the base of her polycarbonate skull in order to access her battery by feel. ‘I’ve got exceptional range.’