Not long ago, I found myself wandering through the expanse of my friend Alex Alessi’s 5th Avenue loft apartment, spellbound by a collection of abstract artwork scattered with carefree abandon against the walls, floors, windows, and furniture.

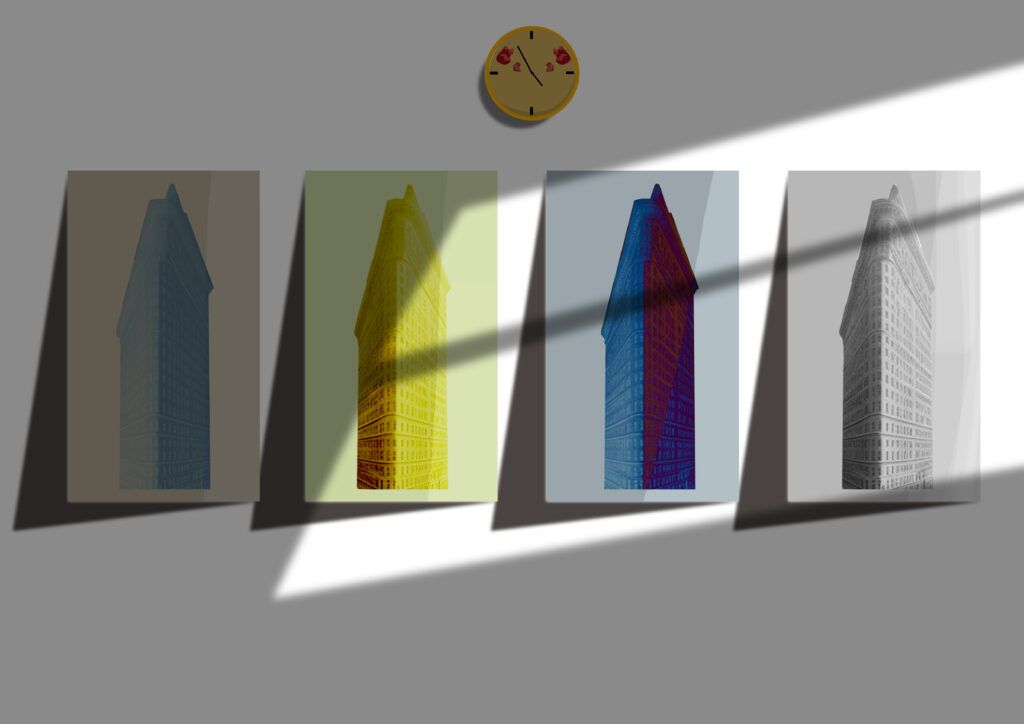

The artist Jerry Greenberg stood over my shoulder. I heard him breathing through his nose like a bull that had just crossed the finish line at Pamplona. This was his life’s work. Each canvas was a vibrant and alluring symphony of form and hue, recognizable as the artist’s tribute to New York’s iconic Flatiron Building.

I might have stood there studying one painting or another for an hour or two. I had no idea how much time passed. Kandinsky, I thought. But not as chaotic. Or Chagall, but not as whimsical. Survage, more so than the others, but not as accomplished. Greenberg’s art was a syncopation of otherworldly retro-futurism and a pandemonium all his own.

Greenberg himself, unkempt and paradoxical, was a figure of cryptic wisdom, his appearance belying a mind in relentless pursuit of profound connections within the mundane. He wore a dark full-length smock splattered with paint, a wool scarf an old girlfriend knitted, and a pair of Converse high-tops. His wealth afforded him the luxury of masquerading as a bohemian, yet he dwelled like a king with a king-sized view of the Flatiron. He yearned for fame yet scorned it for all its superficiality at the same time. For him, art transcended the cavalier Warhol quip, “Art is what you can get away with,” it was a sacred pursuit, each brushstroke laden with existential heft—a puzzle he alone was destined to solve. Nevertheless, this pursuit had left its mark; Greenberg’s scowl, a silent testament to the simmering anger within, suggested a man wearied by the relentless search for an elusive meaning. His was a life on the cusp of revelation, perpetually toeing the line between breakthrough and breakdown.

My connection to Greenberg was a passing chapter in a New York Minute—a fleeting acquaintance birthed from his legendary façade and his ties to Alex. Alex had offered him shelter in the days past, inadvertently turning his loft into Greenberg’s canvas-walled realm.

On a whim borne from the city’s timeless pulse, I had ventured to reconnect with Alex, only to find that time had quietly reassigned roles; Greenberg was the new sole occupant, Alex but a name lingering on the intercom. Mr. Borges, the concierge, buzzed me into this subtle shift in narrative.

So, with nothing better to do, I stepped into the space where once I had marveled at the view from floor-to-ceiling windows—a view that framed the Flatiron with such precision that it seemed an artist’s destined muse. It was a scene tailor-made for an artist like Greenberg, who, upon my arrival, extended an invitation into his world—a world where the Flatiron was not just viewed but immortalized on canvas.

It was one of those New York things—time passing unnoticed until it was all at once apparent while locked in a space with a misunderstood artist whose only concern was how misunderstood he was.

“I can’t recall ever seeing anything this familiar and, yet, bewildering at the same time,” I confessed, to which Greenberg, with the hint of a secretive smile, replied, “I paint only the Flatiron. It’s all I see; it’s all I want to see. And to truly see the Flatiron as I see it, I must see it for the first time every time I see it.”

Though our first exchange was brief, it charged with an unspoken understanding that most couldn’t see what Greenberg saw in the Flatiron, yet there it was, laid bare on canvas for those willing to look beyond the surface.

“Most people think they’re looking at an optical illusion. But even that’s not real,” Greenberg said of his renderings.

My mind grappled with the layers of perception that Greenberg’s words implied.

“You mean the illusion itself is an illusion?”

“I’m saying I’m not sure that which exists right outside my window is there.”

“No, it’s there. I just walked by it.”

“Don’t patronize me. “

“I was just on the street, walking, on my way here, and I looked up at it, and while looking up at it …”

“… it registered in your mind as a building you have always known as the Flatiron.”

“I then proceeded to walk by it and crossed the street.”

Greenberg shook his head. “You may have thought you walked by it,” he said.

“You mean I didn’t walk by it?”

“Of course, you walked by it; millions of people walk by it. But don’t let’s pretend you can see something that isn’t there.”

“I’m not following. Are you saying the consciousness I experience as a human being itself … is an illusion?”

“Not quite.”

“Okay. I’m lost. The illusion of the Flatiron is not that it isn’t there; it’s that it’s flat,” I said flatly.

“How would you know that?” Greenberg challenged.

“I can see that with my own eyes!”

“Have you ever been on the other side of it?”

“Well, of course I have!”

“At the same time?”

“How is that possible?”

“It’s not impossible.”

“You’re either on one side or the other.”

“Then which side were you on? The long side or the short side?”

Greenberg had me cornered; I had no idea which side was which. I knew there was a side facing east on Broadway and a side facing west on Fifth, but I had no idea which side was the long or short side.

“To some people,” he continued, “the Flatiron is your basic 12-5-13 Pythagorean Triangle. There’s a long side and a short side. Now, which side were you on?”

“How would I know?”

“Ah, now we’re getting somewhere! If you don’t know which side you’re on, how can you even tell for certain there is another side?! Like I said, it’s a triangle to some; to others, it may not exist at all!”

At the risk of sounding like a tramp from a Beckett play, I responded accordingly. “Forget how many sides there are—or aren’t—or which side is long or short. I want to know if I walked by it, and millions of others walk by it—but it isn’t there—what exactly is it you see when you look outside your window?”

Greenberg took a moment, bobbed his head, and thought. “Let’s say one’s mind registers it as real. Or maybe one’s mind registers it as something that appears real—like a rainbow! One experiences the Flatiron as real, just as one would a rainbow—but like a rainbow, it really isn’t there.”

“But we’re not talking about a rainbow.”

“Let’s look at it another way. If one can experience something that isn’t there as real, why can’t someone experience that which is real as not being there?”

I paused and let Greenberg’s absurd notion linger before I retaliated with a smirk. “Are you saying the Flatiron Triangle is New York’s version of the Bermuda Triangle?”

“No, Jackass,” Greenberg pounced, “I’m saying the reason I paint the Flatiron is to prove to myself that it’s there!”

Greenberg saw metaphors everywhere, drawing connections between discarded objects and the human condition, between graffiti-covered walls and the stories they whispered. And he expected the same of everyone else in the universe.

“Ever read up on Pataphysics? The science of imaginary solutions?”

“No.”

“Pataphysics is a philosophy of paradox and contradiction. Of imaginary solutions.”

Greenberg’s words hung in the air, and just like everything else about him, they transcended the ordinary, blurring the lines between reality and abstraction. The concept of imaginary solutions sounded like a smoke screen conjured by a delusional post-modern conman. Then again, an imaginary solution only implies the possibility of an alternate solution—I would imagine—and doesn’t necessarily negate all other solutions, including a valid one. In mathematics, a “missing solution” is a solution that is a valid solution to the problem but disappears during the process of solving the problem, thereby allowing any number of possible solutions, real or imagined, to solve any one problem. The Flatiron itself will tell you there are at least three sides to every story.

“I need you to see what I see. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

“Are we still talking about your art?”

“That and all things. You wanna get high?” Greenberg asked.

“I would have thought you were already high.”

“Don’t be cute! Do you want to get fuckin’ high or not?”

My curiosity was intertwined with the threads of Greenberg’s abstract paintings and his touch of lunacy, so I tacitly agreed to partake as I was pulled deeper into his enigmatic world. I came looking for someone else, an old friend. And you know what they say when you begin dredging up the past. You wind up chasing ghosts. So there I was, feeling very much like a ghost myself, who, by looking for one ghost, ended up being entertained by another ghost.

“I thought you and Alessi had a rift,” Greenberg groused as he loaded a bong.

“I wouldn’t call it a rift. Things were said. We drifted apart.”

“So, it was a drift, not a rift.”

“He was successful early on; I was struggling. You know how that goes.”

“Well, I have no idea where he is. Off to find himself, I guess. Europe, Asia, South America, he could be anywhere.”

“What’s his name doing on the intercom downstairs?”

“He never officially moved out.”

“So what’s the arrangement here? Do you sublet from him?”

“Yo! This is New York! People like to be left alone! They don’t want bounty hunters coming after them!”

“I’m just asking, man. Alessi and I were close once.”

“Look, Alessi’s got more money than God, and I’ve got more money than God—do the math!”

At that moment, amidst the canvases and clutter, I made a connection with Greenberg that defied explanation, a connection forged through the unending quest to understand what “more money than God” actually meant.

I leaned against a nearby table, and Greenberg, who had more money than God, was on a battered sofa that bore the weight of countless musings and restless nights and, quite frankly, smelled pretty funky even at a distance.

I felt a sense of camaraderie blossoming in the space between us as I glanced over Greenberg’s dog-eared philosophy books piled in a stack on the floor. Greenberg took a massive hit off the bong.

“We never really hung out, did we?” Greenberg said as a billow of smoke blew from his mouth.

“I was the one lurking at Alex’s get-togethers. I always wanted to open an art gallery.”

“I remember you now, but not quite.”

“Nice to be remembered for not being remembered.”

“Funny. You remind me of Alex, the both of you are sarcastic as fuck!”

“Alex was going to back me.”

“The art gallery? He never mentioned it to me.”

“Well, it was just talk, I suppose. Did Alex ever tell you the story about his great-grandfather? His great-grandfather worked construction on the Flatiron.”

Greenberg’s response was swift, a sharp reminder of his overarching philosophy. “That doesn’t change anything.”

“I’m not saying it changes anything.”

“Look, don’t try to lull me into a stupor with some Ellis Island crap. No bricklayer-from-Italy lullaby is going to change my mind. I’ve read everything there is to read about the Flatiron.”

“Okay. You don’t want to hear the story?”

“I’ve heard it all. ‘The Flatiron Building isn’t flat; it’s a triangle that sits on a square, yet you can walk around it in a circle or take a steam pump lift straight to the top. I practically sleep with the building; it’s in my nightmares!” Greenberg took a deep breath and changed his tone. “I didn’t mean to be an asshole, but I hate boring-ass immigrant stories.”

“That’s all right.”

“Yeah, well, we all have stories, and we all have scars. Half of my mother’s family were wiped out in Auschwitz.”

“Sorry.”

“Me too.”

“Ever hear about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that killed 146 people, mostly women?”

“Sure, fuckin’ horrific —when was that?”

“1911, I think. I’m sure it’s nothing more than a coincidence that the Flatiron is shaped like a triangle. But Alex’s great-grandfather told his grandfather, who told his father, who told Alex, that men were buried alive during the construction of the Flatiron in 1902. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was front page news. But there’s no public record of workers being buried alive while constructing the Flatiron. Anywhere.”

Greenberg’s face changed complexion.” What’d ya’ mean? Alex dreamt this shit?”

“Dreamt what shit?”

“Laborers buried alive!?”

“No, it wasn’t a dream.”

Greenberg looked at me with an expression of disbelief, turning ever so slightly to the Flatiron itself, which was in plain view from the windows, as if it, too, was participating in our conversation.

“Alex’s great-grandfather didn’t speak English,” I continued, “and his grandfather barely made it out of grade school. So whatever was passed down to Alex … through the generations might have been—I don’t know—a misinterpretation of events.”

Greenberg hung on my every word. “It either happened or didn’t happen; no language barrier can misinterpret one for the other, “he concluded.

“Alex spent weeks reviewing old newspapers and historical records for anything that might shed light on what was passed down to him. The Fuller Building, as it was originally called, never reported an accident that killed anyone.”

“Listen to me,” Greenberg said in a low, quivering voice, “I had a nightmare about it. What you just told me. I swear on my soul. And not just one nightmare. Recurring nightmares.” Greenberg stood up, his face ashen, “I would have loved to tell you to your face that Alessi’s great-grandfather was full of shit—but he wasn’t. Who sent you here?”

Greenberg’s “Who sent you here?” cut through me as if it had a deeper meaning. What was I doing here? And why was I having this recall?

“I told you I came to visit Alex.”

“I’m having an out-of-body experience! I’ve dreamt of this! It’s like you’ve burrowed into my head and pulled it out!” Greenberg spun around and clasped his head, “I might even be dreaming right now, man! Don’t go anywhere; I’ve got something to show you. You better strap yourself in for this shit!”

Greenberg rushed me to another part of the loft, where he rifled through a rack of unfinished paintings until he found the one he was looking for.

“This is my nightmare,” he said, showing a photo-realistic painting of what looked like mourners or laborers or the combination of both dressed in black frocks overlooking mounds of sand and ash.

Greenberg then told me the details of his nightmare: Standing in the heart of a construction site, the towering skeletal structure of the Flatiron Building looming above him like a specter, he witnessed the imperiled immigrant workers toiling tirelessly around him, their gaunt faces etched with exhaustion, their eyes betraying a mixture of fear and determination.

As their shovels bit the earth with rhythmic precision, a trench they had carved into began to cave. The trench walls crumbled, and the ground shook beneath their feet. The workers cried out in panic, but it was too late.

The trench collapsed with a deafening roar; a cascade of soil and debris buried the workers alive. Their anguished screams were silenced abruptly as the earth consumed them, leaving only a chilling stillness behind.

“I’m trapped with them,” Greenberg said with a haunted look. “Some nights, I wake up with the feeling that I’m suffocating. And then I hear music playing above me: dancing and singing. There was a ballroom in the basement of the Flatiron when it opened. They were buried beneath the ballroom.”

Greenberg took a moment before he continued, “Then I get up, go to the window, and see nothing but a mound of sand and ash.”

Greenberg looked at me and took a seat on his battered sofa. He reached for the bong and fired it up again. The moment’s truth lay in the fractured remains of a hundred-and-twenty-year-old story passed down to Alex by an Italian immigrant great-grandfather and the nightmares of an aging artist whose imagination knew no bounds.

I could believe both or neither, depending on where I stood and at which angle I chose to look.

Just as one could view the Flatiron Building itself in various ways. Either as a majestic symbol of architectural achievement or a haunting reminder of a hidden, albeit possibly imaginary, tragedy that time and who knows what else had chosen to erase. On some days, when the sun bathed its triangular facade in a golden glow, the building would stand tall and proud, and its iron framework would gleam with a triumphant history. But on other days, when the sky was overcast, and the air was heavy with a sense of foreboding, the Flatiron’s silhouette would cast long shadows that seemed to reach out like fingers, as if beckoning you to unravel whatever enigma it held.

A triangle with long and short sides. It’s all about perspective.

To alleviate his inner turmoil, Greenberg picked up a tattered copy of Heidegger’s “Being and Time” from the stack of books and immersed himself in its pages.

His lips moved silently as he engaged in a dialogue with the profound concepts within. Soon, he embarked on a monologue, delving into the notion that the absence of conscious observers renders time powerless, diminishing its sway over existence. While this idea bore no direct relevance to his haunting nightmares, Greenberg found solace in the belief that isolation could obscure the passage of time.

In this realization, he drew a parallel between the purpose of my visit and the unearthing of what haunted him.

As I reflected on Greenberg’s musings, the notion of how alienating the timeless pulse of the city could be may have been my only reason for attempting to reconnect with Alex.

In a sudden fit of frustration, Greenberg hurled the book across the loft. Then, as if realizing the gravity of his outburst, he clasped his hand over his mouth and fell silent.

“Do you want me to go?” I asked.

“Go if you want to stay, or stay you want to go; I’ve got nothing to do with the rest of my life,” Greenberg replied, intentionally paradoxical and obtuse.

“I might have stayed longer if I hadn’t already stayed this long,” I snapped back in a lame attempt to match his wit.

“I miss the Alex I used to know,” Greenberg said on the verge of tears. “I miss our wide-eyed early days when we were innocent and dreamt the dreams of dreamers. And then the future arrived, and all I now do is look back at the shadows of the dreams we dreamt, searching for whatever meaning I can attach to them.” Greenberg looked at me clear-eyed and direct, “One thing is sure—no matter our differences, the memory of those times together and those dreams we dreamt … keep me from being a fraud.”

I left Greenberg’s loft a short time later. I asked him to get back in touch if Alex decided to show up ever again. We’ll all go out for dinner or something. Not that we were the ‘going out to dinner’ types. Greenberg said he hadn’t been to dinner since “the towers collapsed.”

As I left the building, I looked up at his floor-to-ceiling windows from the sidewalk below to get his sight-line perspective of the Flatiron. I then turned toward the Flatiron. Standing across the street from it and staring at it as if in a trance, my gaze was fixed on the spot where my subconscious had now painted a picture aided by Greenberg’s artwork.

The sun shone brightly on the upper floors of the Flatiron, and even as the city buzzed with its relentless energy, I may have heard faint cries or faint whispers right at the point where the wind was sliced in two by the protruding edge of the Flatiron.

For someone like myself, who had seen Philipe Petit walk on a tightrope between two of the world’s tallest skyscrapers as a child, it was easy to imagine a tightrope between Greenberg’s window and the Flatiron.

My thoughts went underground as my gaze drifted downward to the street below. As never before, I imagined Alex’s great-grandfather’s immigrant co-workers consumed by fear, their faces etched with desperation, their cries for help lost amidst the clatter of construction. It was all so real to me suddenly to imagine what could have happened even though it may have never happened. The collapse of the trench, the suffocating cascade of soil and rubble, the sudden silence that followed, the life that was extinguished instantly.

I decided to walk around to the other side of the Flatiron and then complete a full circle around the building to see it whole for the first time in a long time, if not for the first time. I decided to first walk north on Fifth. I counted my paces as I went. I needed to know which side was which.

I faced Madison Square as the wind began to pick up, whistling in my ears and blowing bits of soot into my eyes. I recalled a story about how the Flatiron caught the winds and channeled a down draft to a particular spot at the structure’s base. Men would fly off their heels back in the day, and women’s skirts would blow up over their heads. I had all to do to keep my footing in the whirlwind before my mind went dim, and I lost count of my steps.

As I retraced my steps and arrived back at my starting point, a subtle shift rippled through the fabric of my reality. It wasn’t the wind this time, but the air around me charged with an energy I couldn’t quite grasp. An inexplicable sense of urgency seized me, compelling me to return to Greenberg’s building as if drawn by an unseen force from the depths of my subconscious. Though I struggled to articulate the nature of this change, an undeniable intuition urged me forward, guiding my steps with a sense of purpose that transcended logic. It was as though time had folded, leading me back to where it all began.

I should have turned around, fought through the down draft, and retraced my steps, counting them as I went, more precisely. But I crossed the street and headed back toward the entrance of the building where I had just left Greenberg.

As I approached the building again, it felt as though I were approaching it for the first time in a very long time, as if I’d been away and was returning to my home.

When I entered the building, I saw a name on the intercom that I immediately recognized as my own—Alex Alessi. But how could that be? My heart skipped a beat momentarily. I called the concierge, Mr. Borges.

“Mr. Borges, it’s um …”

“Ah, Mr. Alessi, how are you?! It’s so nice to hear your voice again! When did you return?”

“I’m … I’m sorry?”

“It’s been a long time, no? It’s good to get away. It gives you a new perspective.”

“Yes, it does,” I said, catching my breath.

“Did you enjoy Buenos Aires? I don’t return often enough myself. I’m sorry we were not expecting you, but not to worry, Mr. Alessi! Everything is just as you left it.”

“How did I … get home, Mr. Borges?”

“I’m not quite sure what you mean, Mr. Alessi. Do you need help with luggages?” Borges asked, mispronouncing “luggage” as “luggages,” something he’d often do. Which made me feel right at home.

“No, thank you, Mr. Borges.”

I blinked, my mind struggling to process things. I’d been on a trip to find myself, and now I’m back. Everything seemed to echo in my mind like a cryptic riddle. I made my way to the building’s elevator, moving through a fog of uncertainty.

The elevator ride felt longer than I remembered. Each floor passed in slow succession, each ding of the bell echoing like a distant memory. The doors finally slid open to reveal the familiar hallway that led to my loft. I fumbled for my keys, my hand shaking slightly as I inserted the key into the lock and turned it.

The door swung open, revealing my loft in its pristine state, maintained by the diligent hands of the building’s crew in my absence. A sense of relief washed over me, mingling with the remnants of the unease from earlier. The loft felt familiar and slightly foreign, like a place I had left behind long ago.

I stepped inside and closed the door behind me, taking a moment to stand there and take it all in. It was good to be home; that much was certain. The loft exuded a comforting sense of solitude, a space where I could retreat from the world outside. I crossed the room and drew open the curtains, revealing the view beyond the window. And there it was, just as I had remembered—the Flatiron Building, its triangular form a stalwart presence against the cityscape. Built around a steel skeleton, fronted with limestone and terra-cotta, and designed in the Beaux-Arts style, it radiated a sense of stability, a reminder that some things remained constant despite life’s uncertainties and the passage of time.

A sense of calm washed over me as I gazed out at the Flatiron. It was as if the building was a beacon that guided me back to myself, no matter where I’d been or what I had been searching for.

Generations ago, my great-grandfather, a recent immigrant from Italy, played a pivotal role in constructing the Flatiron Building in 1902. Alongside him was his young wife, my great-grandmother, who tragically lost her life in the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. The story was passed down through my family, but somewhere in the retelling, the details became muddled, intertwining the tragedy of the factory fire with the construction of the Flatiron. It fell upon me, generations later, to untangle the threads of history. In sharing this tale with my friend Jerry Greenberg, an artist who once crashed at my loft, his imagination ignited. He found inspiration in the misunderstood events, leading to paintings depicting the harrowing demise of Flatiron laborers trapped underground. Jerry’s empathy stemmed from his family’s history of tragic loss, drawing us closer together in our shared understanding.

Despite our differing backgrounds—me, a product of generational wealth studying business, and Jerry, a talented artist yearning for fame—we forged a deep bond. Our friendship was built on shared dreams, memories, and philosophical discussions fueled by leisure and privilege. Jerry had a natural flair for the arts, while I pursued wealth more pragmatically. However, our camaraderie often devolved into heated debates, creating a divide that eventually drove us apart. I would have opened a gallery for Greenberg had we remained friends. I fancied myself a collector at one time, years ago, before time passed, changing all of my dreams into memories and my memories into fragments.

All that remained from Jerry’s cohabitation was a battered sofa, a stack of philosophy books piled on the floor, and a few coarse renderings based on our mutual admiration of the Flatiron Building and the stories we attached to it. He took his most memorable paintings with him.

In the days before he left, Jerry confided in me about the pain he felt in depicting his mother’s family’s suffering in a German concentration camp. Though he didn’t shy away from addressing this anguish in his art, he sought subtlety, recognizing the omnipresence of the past and its profound impact on the present. He said it was there without it being there anyway, which meant there was no way he could not depict it; he didn’t want to be overt about it. What he meant was that the past is inescapable. His words resonated with me, prompting reflection on my own family’s history, particularly my great-grandfather’s loss in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Could it be that, like Jerry, he too grappled with the burden of history, reshaping reality to cope with the pain? I believe a case can be made for Jerry Greenberg’s choosing to commit to canvas depictions of a tragic event that never happened for one that did.

He once said, “I need to know you see what I see. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

I suppose I never saw what Jerry did. At times, our perspectives seemed aligned, but other moments revealed stark disparities depending on our vantage points and the angles from which we viewed situations. Perhaps Jerry purposefully embellished reality, weaving his imagination into the fabric of our discussions. The enigmatic Flatiron Building, with its three sides to every story, seemed to echo this sentiment, hinting that there are always multiple facets to every narrative.

I took a deep breath, allowing the view of the Flatiron to soothe my restless thoughts. The journey, whatever it had been, felt less critical. What mattered was that I was here, in my loft, in the presence of the building that had always brought me solace.

As my gaze descended to the street, my eyes alighted upon a figure at the base of the Flatiron, obscured by the fierce wind that whipped through the canyon-like streets. There, amidst the tumult, stood a man, his form shrouded in a dark art smock that billowed like a tattered flag of defiance in a stiff wind. He exuded an air of purposeful determination as he methodically counted each step along the way with unwavering precision. And in a moment, he disappeared from my view, swallowed up by the recesses of the building.

Jerry Greenberg’s reflections on time and consciousness reverberated within me, serving as a profound meditation on the depths of our friendship.

With a contented sigh, I turned away from the window and remembered I was home.