“Whatever commandment the prisoner has disobeyed is written upon his body by the Harrow.”

In the Penal Colony

Franz Kafka

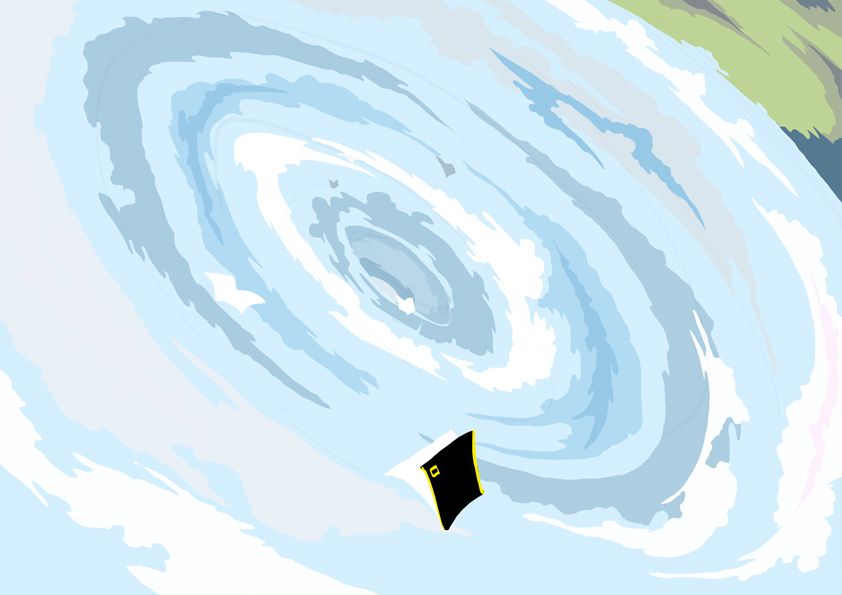

“He stands in the middle of the playground,” Ms. Stebbins began, then stopped, “wait, no, that’s not completely true, Mrs. Taylor. Elias does move. He slowly turns, keeping his eyes focused, no fixed on something off in the distance. But what is so odd, but amazing, is his composure. While all the other children are scurrying about, crisscrossing past and around him, laughing, jumping, screaming, Elias quietly rotates, his eyes−fixed. I imagine that if you could look at him from overhead, he would appear to be like the center of a hurricane, its eye, I, ah-.

Ms. Stebbins paused to look over in the corner. Elias was quietly thumbing through a National Geographic, wearing earbuds, listening to Mozart’s “Jupiter Symphony.”

When she turned back to face Elias’ mother, Doris Taylor was looking out of the window, studying a configuration of limbs extending out from a large oak tree. Whispering under her breath, unaware she could be heard, Mrs. Taylor, said,

“Miro, perfect copy, early sketches . . . Outside the Circle, it-”

Mrs. Taylor’s eyes quickly dropped, now focusing on Ms. Stebbins who was blushing, trying to be discreet and unobtrusive, but failing. Doris Taylor curt and questioning, said,

“Yes? So? Elias does not play well with the other children? No surprise, there. Fine. It has been acknowledged. Is that the reason I have been summoned? Impossible. Really? Is playtime compulsory? Graded?”

As Mrs. Taylor continued to protest, Peggy Stebbins nodded and smiled, careful, to keep her eyes focused on the mother’s face as she dialed back the volume to zero on her voice, thinking,

‘The mother is harder to read than the son. Such a hard, impenetrable façade. Is she serious or just gaslighting me? Elias is such a dear, I-‘

Doris Taylor’s voice broke through, shattering Peggy’s momentary defensive bubble.

“You’re very passionate, a fine quality. Something, I sense, no, more than that, I actually see, it, even experience it−now, here sitting with you, really, I do, Ms. Stebbins. Bravo!”

Doris’ voice was now soothing and melodic, seductive and calm.

“My word, was I ever so young? You don’t simply wear your emotions, they’re like a fragrant wreath strung around your neck.

“All a body has to do is close her eyes, draw in a breath and voilà, there you are, gently ministering to, then marshalling all the little ones about like a mother swan her hatchlings. Elias is fortunate to have you as a teacher.”

Ms. Stebbins was, now, completely−lost. Was this woman−mother−sitting in front of her bipolar? a grifter? con artist? or,

‘Whoa, she’s actually more ill-at ease, than I am, right now,’ she thought and nodded and quietly continued to listen as Doris Taylor said,

“Yes, quite prescient, really. When you compared Elias to the eye of a hurricane, what with all the other children running around him, crisscrossing, stumbling, laughing, playing. That image, well, truth be told, I immediately saw his father. Yes, his father, Arno, was given to similar behavior.

“We were at the World Cup: Sao Paulo, a night match. Constant noise and activity, what with all those confounded, horrid horns blaring, and more than eighty thousand fans screaming, and in the middle of it all, Arno claimed he saw a line of shooting stars dot and fan out into a line of notes. Said he could actually hear Paul Desmond’s alto sax, a riff from Take Five. He, well-”

Doris abruptly stopped. Her eyes left Ms. Stebbins’ dutiful stare to center on and then begin boring a hole into the wall just over and past Peggy’s left shoulder. A long, silence followed as Doris drilled farther down on a Sunday morning, five years earlier.

Arno sat down at the piano, closed his eyes then struck four keys at random, paused, turned around to Doris and said, “Connected?”

She put down her coffee, shook her head: “no” then said, “OK, I know there’s more, so?”

Arno smiled, saying, “We, I mean, us−Man, we’re the notes. Each a random sound, life, consciousness sprung to life all to immediately start wandering around a place in which he’s completely ill-suited to inhabit. After a brief moment, he expires with little or no real connection to any and all that is around him, save for a few wondrous suggestions, sounds, sorry, music or dreams. So, on some level we, yes, we must touch it, that is, the vast expanding light that runs out and through the universe, but how?”

Arno plucked four more notes and listened as the notes rose up and died in the air, and said, “And surrounding him, us, is all this amazing life that has a direct and intimate line into the planet, the universe and all the light that created . . . life. Us?

“I look at you, hold you, make love to you, still we, even as close as we can get to one another while making love, we still run into a thin wall that separates us. Then I sleep. I close my eyes and you wash over me in a wonderful, glimmering lucid dream. When I wake, I actually feel more satisfied than after sex. We have danced and intertwined in a way that . . . that I’m not sure yet, but am working on it.

“Seems that each of our consciousnesses is like a particle, perhaps, yes. So, if that is true, then perhaps we can exist in the same time but in different places. But as the quantum world dictates, as we measure it, another change takes place. So, why not, could it be, that our consciousness is like a shadow of light? Maybe it can carry “us” to realms and ideas that are, well, beyond us, kick us outside of our heads, allow us to meld, mix and match the light of the universe without being changed. Maybe that is “our” connection, one that the other species lack.”

Arno smiled and shook his head, played four more notes at random then said, “Or not. We’ll see.”

“Mrs. Taylor?” Peggy whispered after the silent pause became uncomfortable.

“Mrs. Taylor, may I, do you need something?”

Doris Taylor blinked her eyes quickly, smiled sheepishly, then said,

“Seems our little Elias has a lot of Arno . . . rest his soul, in him. I-”

Mrs. Taylor’s eyes watered, then she looked away and laughed, nervously, before quickly composing herself, asking,

“May I smoke?”

“Elias! Yo! Butt-face! Meatball! Jackass! See?” Dexter said to Travis as they watched Elias stride past them across the street and continue on.

“Nothing!” Dexter said shaking his head, smiling as Travis watched Elias disappear around the corner, clueless that Dexter and he had shouted at him from only thirty feet away. As Travis started to speak, Dexter held his hand up,

“No, don’t get wrong. Love the guy! Amazing to watch him at a party. No kidding. He’s so fucking quiet−glib; women are like bees to honey, other people? I swear, some even walk up and check his pulse. He rules the floor.

“Seriously, pretty soon, he’s got the whole room circulating around him. But him? Elias? Mars, Venus? Who knows? Oblivious, still, he owns the room, and he never laughs−ever! And believe me, everyone in the house has tried everything to get him to at least−chuckle.

“I was the first to take on the challenge. Movies. From old to new, old-school zany to surreal: “Duck Soup” to “The Life of Brian.” Nothing, goose egg. Jack took him to one comedy club after another. Again, three strikes. J.D.? He tried joke books. Elias read them front to cover in a couple of hours, nodded, yawned−zilch.”

Travis shrugged, shook his head, then said,

“Leave child’s work to children and all you get is a mess of Playdough and cookie crumbles.”

Dexter looked confused, until Travis reached into his front pocket and pulled out a large joint, saying,

“So, why do you think? I was planning on smoking this with, Alice. Helps her get into the mood, and yeah, whatever. I can roll another later, c’mon.”

Sprinting after Elias, Dexter and Travis caught up with him in less than a minute. Turning onto 4th street, both stopped as if they both had been blinded-sided by a bus. There was Elias staring straight up into the sky−cackling. He was laughing so loud, pedestrians veered around him, then stopped, pulling out their earbuds, staring, then one-by-one they started videoing him.

As the fourth person stopped to capture the strange fit of laughter on 4th Street, Elias erupted into a full-blown guffaw. A crowd of ten, and growing, swelled around Elias.

Travis showed the joint to Dexter, then said, “No need for this, now. What gives? You said he’s never laughed.”

“Don’t fret, sweet. Your teacher is very nice. Ms. Stebbins is just, ah, no, I won’t go there, she adores you, she does, really,” Doris whispered to Elias as he sat staring out of the picture window of their townhouse.

Across the street, under the gleaming, curved plate-glass, trimmed in Art Deco white, blue and aqua tile, resting like a sleeping predator was a vintage ’48 Jaguar. Insistent and gesturing, the overly-animated salesman, desperate to close the deal was beginning to annoy the potential buyer. Watching the silent action play out in front of him, Elias was reminded of,

‘Him! Father’s favorite,’ Elias thought, ‘the one who wore the striped shirt and had the painted face. Father loved him. Mar . . . Marcel, yes, Marceau. Father repeated his name slowly so that I would remember it. Father said that Marcel Marceau was the only person who could ever step out of time, only to turn around and use it−time−as it continued to expand out,

“See, there Elias? Movement, expression and emotive purpose, it’s like a thought or image popping out of your head, then walking up to shake your hand,” Arno Taylor said to Elias as they watched the PBS special together.

“Don’t fret sweet, I know it’s hard. I miss your father, too,” Doris whispered as she rubbed Elias’ head, then followed his eyes across the street to the Jaguar dealership.

Now, the salesman’s face had lost its smiling, earnest sheen. He was all granite: grave and somber; nodding, agreeing with each and every silent utterance that came from the client’s mouth.

Then, suddenly, granite dissolved into syrup, as the salesman bent backwards, almost falling from his over-reaction of complete and utter surprise, laughing, slapping the client on the back.

As Doris watched Elias, the air seemed to thicken, vibrate and respond to her thoughts. Superimposed on Elias was Arno−asleep next to her. His Roman nose nestled deep into the pillow, his long silver hair almost disappearing into the pastel pillow case.

She had been his pride, his number one grad assistant. She? Revered and hated by not only the faculty, but the rest of the doctoral students. The “colossus and his nymph” was the most benign of the labels that colored the chatter that hung over and followed them everywhere. Doris, though, adored it, at least for a while. Then she tired of it, hated it, then grew to love it−intensely.

Watching Arno deliver a lecture, Doris watched as the room packed to capacity, sat silent and rapt, their eyes never moving from him, thinking, ‘We’re all sectioned off, pressed into a prescribed form or mold, so? I’ll take hubris over envy. Neither wins, both must founder, but at least I’ll have more fun during the wreck.’

“What’s twenty-five years among friends,” Arno whispered as they made love for the first time. “Hey, I’ve got it! What’ll really piss them off is if we get married! So?”

‘Same gorgeous forehead and granite-gray eyes as his father, only brighter, firmer and more radiant. Same steely-stare, put a black-and-white filter over him, and he’s a perfect match for Arno at the same age,’ Doris thought as she reflexively reached over to pluck a fresh cigarette from the fire-engine red and cream pack of Winston cigarettes, sitting on the coffee table.

Now silver-blue smoke joined the viscous, vibrating air, curling up and away from her Winston. Elias wore a reactive halo, now, as Doris’ reverie and swirling cigarette smoke worked the air into yet another projection, another living-breathing tableau of her angst and loss.

‘His eyes never move from the target,’ she thought as she continued to watch him.

‘Is he really looking at those fools or is he going past, deeper, extending himself down and through something that-’

“You hold it up to sunrise and the sunset,” Arno said to Doris standing on the balcony overlooking the Bandol seaside.

It was a hand-blown crystal ball filled with tiny prisms and crystals. Arno had bought it in Stockholm, he carried it with him−always−from that point on.

“If you are to really know me, you must look through this love,” he said to Doris as he motioned her out to join him.

“Aren’t you even going to get dressed?” she asked.

“Why?” Arno said, “You shouldn’t either! Hell, it’s France, come on! The temperature is perfect!”

Nude, first light creeping up and over the Mediterranean, Arno pulled Doris into him then thrust the glass ball up to meet the sun. A mix of white, blue, yellow and orange light speckled and dotted their faces, the tiled balcony and the rocks below. A moment later, a wash of green, blue and purple raced around them as Arno slowly rotated the ball.

“It is never the same,” he whispered, “different each morning and evening and any two days are never the same. If you concentrate and adjust your breathing, you swear that it−the light takes you, lifts you, then eases you into a slip-stream of-”

Arno stopped, took several long, deep cleansing breaths, closed his eyes, then whispered,

“This!”

Elias’ eyelids rarely moved as he watched the salesman drop to his knees; the client shaking his head, motioning for the salesman to rise. But before either man could move, a new puppet arrived. Standing behind the client, now, gently massage his shoulders was, a long, lithe, woman wearing a one-piece body-suit, oversized sunglasses, and make-up that seemed to walk on its own every time she spoke.

Thrusting her head back, laughing, her face seemed to rise up and inhabit the air with a swirl of pink, blue, beige and red. As she continued to rub the client’s shoulders, the salesman, who still had not gotten back up on his feet, appeared to be praying to both the client and his long-legged woman.

A moment later, the man and the lady moved to bookend the gesturing salesman. Standing on either side of him, the woman urged the salesman to rise, while her partner shook his head violently, insisting the salesman stay down.

“Why do you smoke so much, mother?” Elias asked, never moving his eyes from the silent feature playing out in front of him.

Doris felt a pang of embarrassment, sending her reverie crashing and burning on the floor in front of her. Suddenly the smoke seemed to singe and burn her nostrils, followed by a momentary fit of anger that was immediately washed away with a chilling pang of guilt. Doris quickly snubbed-out the unfinished Winston, whispering,

“Just sharpening the teeth of the harrow, sweet. Helping that wondrous contraption perform its task. If a new imprint is to appear, why not make it clear and deep, radiant and lasting. I’m sorry, sweet. I mean, well, it’s the way memory works.

“Images and feelings bubble up from places you never imagined, and then begin to prick and stick and steal a little bit of happiness away. I thought the smoking would help me cope. Seems it only helps me focus, concentrates it, making it more real than, never mind.

“It surprises me, that I still miss him, even more−now, than when we lost him two years ago. Smoking, at first, softened the jabs and pricks of all those wonderful, complicated memories. Now? Seems the teeth of the harrow have a mind of their own. Writing and rewriting a story of their own. I suppose, even memories grow, thrive, morph and transform, not just themselves, but the person who possesses them.

“He kicked down so many barriers, allowed us to see well below the surface of the obvious. Then, the very next moment, after a brief pause, having seen both the surface of the thing and its beating heart it all became−revelatory. That somehow, we were all dancing through dimensions, light and sound that-”

“What’s a harrow, mother?” Elias asked.

Doris smiled, shook her head, leaned over and kissed Elias, saying,

“Oh, your mother is just being silly and self-indulgent, sweet. It’s from a story I read in college. It was a machine, a form of execution on an island, a penal colony. The prisoners sentenced to die were tattooed over and over again with a description of their crime. Harrow is like a set of spikes punching the ground to break it up. In the story it injects the ink into the skin of the prisoner.

“Don’t bother with it, sweet. Mother is just a little sad. Memories are like the spikes, sweet, that punch over and over, deeper and deeper, until you are not quite sure who is really in control. And, well yes, add another spike to the harrow as well. It was your father who showed me that story. He was wonderful that way, never stopping always exploring and sharing, and . . . that’s enough of that. Yes, these horrible tobacco sticks help distract me. And yes, I know it’s a very bad habit, sweet, I’m sorry. I’ll stop, soon, promise.”

Elias looked away from the window and straight into his mother’s eyes, asking,

“So, what was it he meant when he said-”

Doris held her hand up,

“I knew you were thinking of that, it was one of, if not his favorite expression: “When the world shows its ass!” Yes, sweet, I remember. It was the only curse word he ever used in front of you. He always felt . . .”

Arno Taylor watched his teacher, with great flourish, sweep her hand her hand across the world map she had just pulled down. Instead of the blackboard, the sixth graders were now staring at the hard, shining green, brown, blue, orange and white colors, all shaped and formed by straight, crooked and curving black lines that comprised,

“Our world!” Mrs. Lamont announced to the class, “At least as it appears to us−now.”

A hand immediately shot up.

“Yes, Debbie?”

“How is it? I mean how could it change?”

“Good question,” said Mrs. Lamont as she pulled down another map, with very few lines, almost no color and large empty spaces.

“This, class, is how the world looked to the people alive in 1587, when they believed the world to be flat. See? Without science, man believed the earth to be much smaller and a flat surface. So-”

Another hand shot up from the rear of the classroom, stopping Mrs. Lamont.

“Yes, Arno? Is there a problem?”

“So are maps and history simply . . . stories? The books we read, are they just a matter of which version works best at the time? Is there a way to step out and look over everything as it really appears outside of our senses? Aren’t in sort of a prison? Don’t they, I mean our senses change what we see and read. Has anyone created a map or book or history that is completely neutral? Don’t we read and see what best fits who we happen to be?”

“I, I’m not sure what you mean Arno, explain,” said Mrs. Lamont.

Arno took in a deep breath, paused for a few seconds, then said,

“The pictures of earth taken from the moon, deep-space telescopes, would it, is it possible that even the images of earth and us, and the ideas we think we know as true, ah, what I mean, is, is it possible that they are just another flaw, a mistake? That if we were ever to find a way to step outside, I mean, actually remove ourselves from inside of our own heads it, all of this here and now, the new map, everything we think is true, would be just . . . well, like that flat earth map?”

Mrs. Lamont looked at the floor, then up at the ceiling and sighed. A deep, chilling silence filled the classroom. No child felt comfortable, and all were afraid to speak.

After another ten seconds, Mrs. Lamont cleared her voice, started to speak, then stopped. Walking to the rear of the classroom, her crêpe-soled shoes squished and squeaked as she made her way to Arno’s desk.

Once she arrived, she stared down at Arno’s up-turned face. The two of them stared at one another for several seconds. Arno felt a steady stream of sweat begin to trickle down from his armpits, tickling his side and staining his shirt. A moment later, Mrs. Lamont said,

“Again? Such a disruptive and contrarian young man! We’ve been over this!” Mrs. Lamont’s voice cracking with exasperation.

“There are nineteen other people in this this class. I’ve spoken to you and your mother. Lord knows, I’ve tried to be patient. I, oh, never mind. Go to the principal’s office. The three of us will sort this out, later.”

“. . . exiled. But he was so free. Your father smiled at that. Said a life of solitary confinement has its advantages. He said it walled him off from all the white noise that seems to fill the heads of−everyone. He knew there were no actual rules. Each day was completely unconnected, a new expression, unchanged and unfettered by the day before or after. We both miss him, so very much, don’t we, sweet.”

Doris looked over at the dealership, the expansive plate-glass window gleamed under a wash of sunlight. Elias’s eyes had still not moved, continuing to watch as the client and his long-legged companion eased into, then wriggled into the soft, snug embrace of the dark green’48 Jaguar. Searching, Elias found the salesman bending low, gesturing, his mouth moving in a silent barrage of silent banter as he ran his hand along the front fender.

“Still having the dreams?” Doris asked Elias, the bright-colored, lucid dreams, the ones that take you-”

“I like them more than-” Elias paused, never moving his eyes from the dealership window, “more than any of this.”

“This?” his mother said.

“Yes, all of this,” Elias responded, “I even get to see father. He’s young, and laughs a lot−hard. He really seems happy. Wants to take me everywhere. Not around here, but around the rest of the world. Places I’ve never seen or read about. He’s-”

Elias closed his eyes and took a long deep breath, then turned to look at his mother, saying,

“He said last night, ah, I mean in the dream, that it’s useless to listen to what people say. Better to watch how they move, what their bodies transmit; that it’s like a language we all forgot how to speak, but can relearn it very quickly if we just stop and pay attention.”

Elias turned back to watch the play in the dealership showroom, saying,

“That man really is not rich, and his girlfriend is not his friend at all. And that salesman is lonely and scared and wants, desperately to go home and cry. Father was right. It’s a language that we can pick up, if we just watch closely, and allow ourselves to step out of our own heads.”

Elias’s housemates, Dexter and Travis, stood and watched as Elias bent over, grabbing his sides, desperate to catch his breath as his laughter turned−torturer. Hyper-ventilating, begging for help as the laughter roiled and kicked from the inside out.

Most pedestrians gave him a wide berth, shaking their heads, some in disgust, others in envy as they detoured around him. Soon, though a large semi-circle of people, cell-phones in hand began to nod and laugh as they videoed and immediately posted: “Lunatic on the Sidewalk.”

As they crowd continued to grow larger, Dexter and Travis punched their own cellphones and were horrified to see Elias the subject of now, viral, disgust, derision and hate:

Post included, “Life on Crack!” “I thought Charlie Manson was dead” and “Where is my Glock when I need it?”

Travis and Dexter tried to stop the filming, pleading with the crowd,

‘He’s fine, really,” Travis said, “just a matter of taking his meds. No need to worry, and please, enough! No more videos, thanks.”

Then, as the crowd dispersed, and Elias laughed on, Dexter and Travis looked at their and then back at one another, simultaneously, asking,

“How?”

Ten minutes ago, Elias had waltzed down the stairs of the old Victorian house he, Travis, Dexter and J.D. rented in the West End section of Salem. He had a tutorial to give to a

small group of high school students from the School of Advanced Science and Math, deciding on such a warm and sunlit day to walk the two miles. Elias felt unusually well-rested and energized, after waking up from a, particularly, vivid lucid dream.

In the dream, his father, Arno, who had passed away twelve years ago drove up to the front of the house in a beautiful vintage Jaguar convertible. His father was the same age as Elias: twenty-two.

Pulling up and parking in front of the house, Arno shouted over the revving engine, “It’s too nice a day to study. Anyway, it’s all about the light, isn’t it, son? See?”

Arno pointed to a broad beam of light that rose up and splintered into a mass of particles, then swirled to form long, delicate waves that washed over both of them.

“Particle to wave, wave to particle and all at the touch of finger! Just knowing how to insert yourself in the slipstream, son! Feel that?” Arno said, “So, you pick! Any place or time. It’s on me! We’ll just ride the flow through what’s already been and is still being imprinted. Take off today and arrive yesterday as we make our way any and every dimension you choose.

“It’s like hitching ride on the cuff of time, if you know where to look. Just my way of shooting a moon back at the world. If they want to show their ass, well, I’ll show them mine!”

Stepping out and onto the sidewalk, Elias’ first step dropped him straight back, down and then through himself, ‘My own black hole,’ he thought as he felt compressed down to a tiny point, before elongating, then stretching out into a wave, his eyes covered and filling with elastic green shoots forming in the center of his head.

“Let it work son! Let go! It’s just the light of the stars hooking up the with polarity of the earth,” Arno whispered. “Your own gravity has taken hold, turning you inside out from yourself. Ain’t that one big kick in the head. Kind of like being a tuning fork, a perfect circuit, if you will, all the energy moving, emerging, recycling, both light and dark unseparated. And you’re a part of it, there in the center of you head. Fun, isn’t it?” Arno shouted, “where to, son?”

Mashing down hard on the accelerator, the car jumped, the road narrowed, the high-rise buildings on each side of Main Street dissolved and Elias and his father, Arno, found themselves on a small, verdant green bluff.

Looking out and over what first appeared as grass began to vibrate. Elias felt his core shimmer, the inside of his eyes turned in and on themselves as they expanded and matched the light. What he first took as sound was simply more light splintering and recalibrating, running through the compete spectrum−instantaneously.

“It’s what I meant about the false sense of reason and purpose connected to language. I know! You were only nine! Still, I had to say something, give you a hint, leave a clue, so that your unconscious could knead and roll it, fold it and refold it until−now! See, son? You’re free of yourself.”

Elias looked down, took a deep breath and wondered, ‘How?’ as he pulled into his lungs not just the scent of the water, but every imaginable form of it, again, without limits.

‘Water?’ he thought, but then, realized, ‘no, water is but a label that fences in the actual purpose and constitution, an abstract notion that founders when-’

“Yes, you see it! It’s the language that fails us, imprisons any hope of expansion! Good!” his father shouted, “let it all fall away, son. You’re first step outside of your head. Relax and move faster. I’ll use the old words, until you take a few more steps. After that? No head, so there will be nothing constraining you, nothingto get in the way.”

The sky was a mix of aquamarine and white. Several small islands dotted the river? sea? sky? that ran out and away from his perch.

“Yes, relax, happens, the first time out,” Arno said as he peeled off his shirt and pants and dove straight down and into the shimmering blue water. Popping up, he shouted, it’s perfect. Don’t worry. First time it always looks like land, when it’s really water. Perfect seventy-two degrees. Not too hot or cold.”

“OK, fine. Stay up there. Enjoy the−yes! You are floating,” Arno shouted up just before diving back down into the water.

‘So, it’s a slip-stream, right? Outside of my head, a jail break. Finally freed, my conscious-unconscious mind becomes a part of a slip-stream that meshes into a beam of light, right, dad?’ he thought, and to his surprise Arno answered without words,

‘Yes! Now, just don’t fight it!’ Arno responded silently from below as he floated on his back, reaching up to catch, refract and redirect still more light. The two of them began to laugh. As they laughed longer and louder together, their sounds meshed and melded, became like twin tuning forks struck and humming in perfect unison.

Rising up, taking a long deep breath, Elias was surprised to see Travis and Dexter standing in front of him; both concerned, confused and desperate to discover what had just happened.

The three of them stood silently staring at one another for close to ten seconds when Travis started to speak, but was stopped by Elias’ raised hand and calm, soothing voice,

“Just shooting a moon with the old man, fellows, shooting a moon . . . or I don’t know, maybe dodging the harrow. The old man got me a day pass from the penal colony. Seems the only way out is to light up, then have a good laugh.”