Lee was kneeling next to the couch, where her mother lay with her head propped up on an old, worn, floral print pillow.

“That’s it, Ma. I’m calling an ambulance,” Lee said. She wiped her mother’s forehead with a damp pink washcloth.

“I’m fine, Lisa, honey,” her mother said, pushing Lee’s hand away from her face. “Stop worrying about me so much.”

“Fine,” Lee said, standing up beside the couch, and raising both hands in the air as if someone was pointing a gun at her. “I’m done.” She folded the pink washcloth in half and placed it on the wooden coffee table.

“Lisa, honey, please put a saucer under that washcloth before it stains the coffee table.”

Lee tried to remember how old she was when she started calling herself “Lee,” instead of “Lisa.” Ten? No. More like eleven, she thought.

All the fights she had with the neighborhood boys, and the names they called her. “Dyke.” “Butch.” The black eyes, her nose broken, twice, and her mother never asked her why.

Lee lifted the wet washcloth from the coffee table and placed it on the saucer.

“Lisa, honey, go to work. You’re going to be late.”

“Work can wait, Ma,” Lee said.

“No honey, you’re the shop steward now. They need you there. A union carpenter and a shop steward, to boot. Oh, your father would be so proud of you, Lisa, honey.”

“Okay, Ma, I’m gonna go to work. But I’m calling you at lunch, and if you haven’t stopped coughing by then, I’m coming home and taking you over to see Doctor Emerson on Roosevelt Avenue,” Lee said, as she bent over and tucked in the edges of her mother’s blanket under the couch cushions.

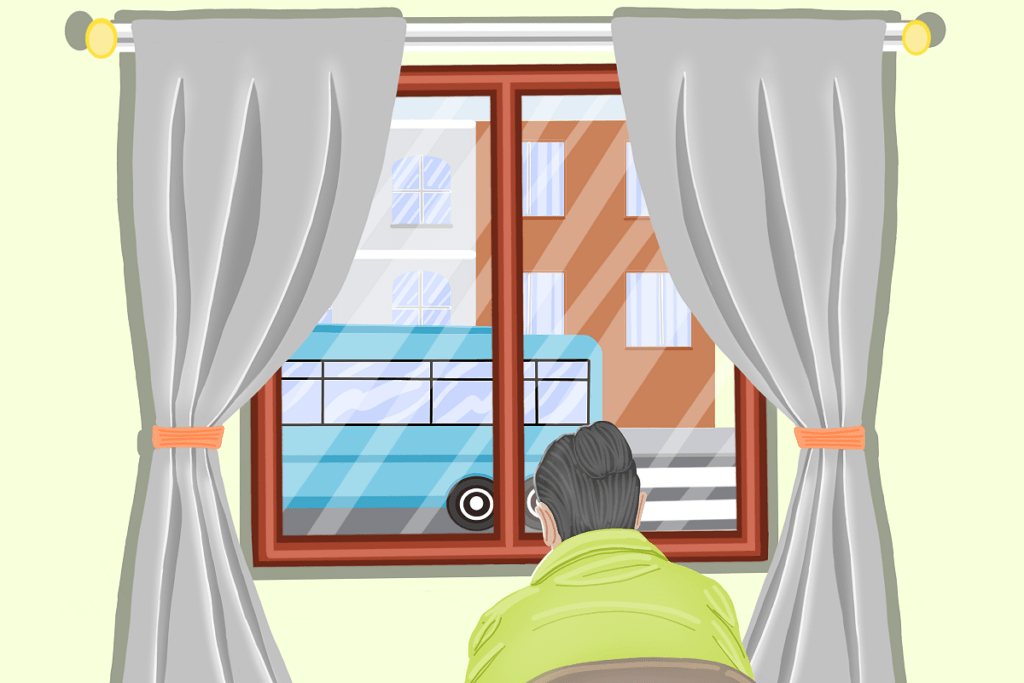

“Lisa, dear, don’t close the curtains, I like to watch the buses go down the street. You know, some of those buses are double deckers, like they have in England.”

“Yeah, I know, Ma,” Lee said.

Lee was loading screws into her tool belt when Tommy came down the hallway. “Got a light? I left my lighter in the shanty,” Tommy said. Lee pulled out a match, lit it, and held it up to Tommy’s face.

“I’m sorry, Tommy.”

“Sorry? Why, what for?” Tommy said, blowing smoke into the air.

“For being late today, I had some family shit at home,” Lee said.

“You know the deal around here. Family comes first. You’re on, on 12 today, with Mikey,” Tommy said.

“Copy that,” Lee said.

‘Nice shooting, killer, you almost looked like a real fucking man on those boards, mo,” Mikey said, wiping the sweat from his face with his blue bandana.

“Like you would know, bitch” Lee said.

“No, really, mo, throwing up twenty-five boards before lunch. I’m impressed,” Mikey said, unclipping his tool belt. “Come on, mo, it’s lunchtime. Let’s get to the bar.”

“Wow. Looks like you got the whole gang today,” Cindy said, as she began tossing paper shamrock-shaped coasters down along the bar, like a blackjack dealer.

“Friday’s for the men, right, Mikey?” Tommy said. “Plain fucking English, mo. Plain English.”

“How many wings we talking about– 50?” Lee said.

“That will get us going,” Tommy said, wiping beer from his mustache with the back of his left hand.

“Here you guys go,” Cindy said, as she put down two big bowls of buffalo wings. “Hot on the left, mild on the right.”

“For the men,” Tommy said and held up his beer.

“To the men,” Lee said.

“Plain English, mo,” Mikey said, and he reached for the hot sauce.