I

Three shadows blended into one huddled mass, the rain falling around them. Secluded by damp cement and wild brambles they were half aware of voices passing just outside along the rusty chain-link fence. They stood between dirty blankets, empty bottles, pulpy paper bags, and discarded needles. Litter that marked the uneven footpath from sidewalk to underpass alcove.

“She’s just fine, cantcha see, she’s jesfine,” Joel walked over, grabbed at and missed the obvious take in his opponent’s hand. Right now, his enemy was a small man with long shorts and a heavy beard. An invader who sniffed out and discovered the concrete enclave which sheltered the small family. Trouble was this enemy had brought the pickup they had been craving.

Joel had protested with a rattle in his voice, “We don’t knowyur stuff, whr u?” As assertive as he could manage with lungs damaged from years of exposure. He braced against the challenging stare.

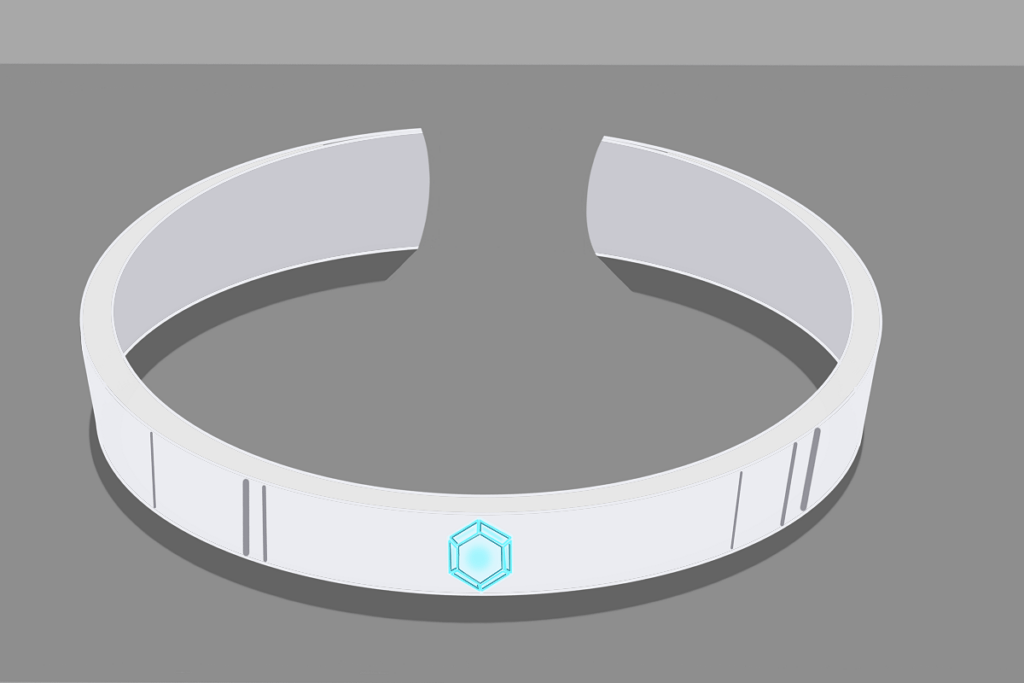

“Im fine, juss a hit, thas all, thas all I need,” Dusty muttered, half-grinning toward the two. She reached out to pat her man with her left hand, watching it reach for his dirty flannel. A flash of blue and silver interrupted the line of her wrist. It was beautiful. Who was it who gave it to her? Distracted by the deep blue cut in metal and stone, she withdrew it quickly to protect it from the invader.

“– just take it,” the stocky pinch of a man with a dirty beard and shaggy eyebrows replied. It was enough to warrant a protest of hesitation then meek compliance. A milky nipple for a hungry babe’s mouth, that’s what the junk was.

After, Joel’s stiff body leaned into her by immeasurable amounts only she could recognize. His weight pressing on her body was proof she was alive –she translated it into love. His stupor, regardless of intensity, never stopped him from checking on her.

“You . . . ‘kay?” His heavy lids and long dark lashes fluttered. He moved his tall and lanky frame by willing it, not by any skeletal progress, but by sheer defiance of gravity. At least it seemed so when his pale face and protruding cheekbones appeared in the narrow shuttered windows of her perception.

“You oh’ …kay?!” Alarmed, though mellow in its initial intonation his short question became a declaration knocked into her consciousness by his bony forehead weighted into her matted head. She thought loudly and knew he would hear her.

Yeah, I’m okay. I love you.

“Oh.kayh,” pronounced and determined as he was, he was an ineffective, hollow man. A scarecrow propped up by rotted wood and left to stand in an empty field. His earnest concern for Dusty was consumed by the numbing of all of his joints, his heart and finally, his brain. He slumped against the cold concrete that was their living room wall like a wet towel against pavement.

When a chilly northern breeze invaded the tight huddle of sleepy dopers, Dusty backed away and moved with zombie-like stealth down the littered path toward the clean sidewalk, stepping out through a hole in the rusty wired fence. It snagged her sleeve on the way out and efforts to disentangle herself liberated her from her stupor. She chastised the fence and shuffled down the walkway toward misty neon lights.

Blinking away the scattering patches of dusk, regular items lost their shape and depth –only outlines were left of a street bench, of a parked car, of fences and street signs and store fronts and parking blocks. Sometimes the curb disappeared and reappeared. Sometimes her weathered hand, just an outline, grasped at a fading promise.

late august summer when the ferry to martha’s dumping bags on the floor –that room ridiculous wallpaper we ran outside to see what the place we knew was more –a place apart –our summer –it was the sand, dammit, so warm, plate size puddles, easy to sit in act out in –warm, powder-like, grit to sink your butt in scoop in knowing at four we was gonna be late

Her left arm ached. And then, without any memory of the origin of the pain, she heard a dense throbbing. Her skull became a soundboard. Why wouldn’t it stop? A drumming in her bones started at her wrist and traveled upward in spasms until it dialed into her brain through her swallowing phlegmy throat and congested ears. It had crossed her heart hope she dies –hopes i die –numb it away– any way– Dusty’s final take tricked her with a fast effect, then too fast a let down. More disorienting than usual, it left her mind sharp but her body kind of paralyzed with feeble throbbing –rhythmic in and out and ever after. Was it a sign that the stuff didn’t work on her no more? Joel didn’t trust, Dusty was too trusting. Even if a protest was appropriate, her lips, tongue, and jaw were often too stiff to work against –the words were hard to manage until it kicked in. Maybe she did say, but no one heard? A gift hit, no matter how bad, was still a gift.

II.

Georgetown had been a strip of neglected sidewalk and thirsty trees when she moved in ‘96. Even then, “The Deep Drink” was a dingy bar with permanent grease stains pretending to be stained glass. It catered to regulars, the occasional poor young artist, and daring couples exploring the city. Most of the men who crossed the worn threshold had a favorite spot, were over fifty, and looked displaced from a bygone era. With yarn heads shaped like the hat on their knee and facial hair of various shades, dirty wrinkles and misbuttoned shirts, the regulars were a gnarly pack of individuals who made others suffer through their independent streaks. Most were unmarried. Attempts had been made but it was never their fault if it didn’t work out. Clinging to a death-routine they relied on the caustic stench of the wooden bar and the comfortable smell of freshly drawn draughts.

When they woke before dawn, they suffered for hours until they crossed that too-familiar threshold. When they fell asleep –dense rocks on soft sand– they dreamt of dim lights and grins, stiff fingers wrapped tightly around cold glass. They smelled amber pours and heard damp comments from their seat partners.

Dusty’s matted head leaned against the front corner where gnats had convened in an abandoned web. Cut into the dark wooden table were faded names, poorly spelled promises, splintered hearts. She traced one dime-size heart over and over feeling small pleasure in how its rough edges threatened to cut into her calloused fingertip. Lids heavy, loaded, her burdens were about to be laid to rest.

Lois worked under the dark red lights conscious of how the next four hours would weigh out. Each hour her massive body would feel heavier and less likely to move from behind the glowing bar. Flaccid underarms slapped against her breasts when she moved to fill up a neat row of shot glasses. In a knee-length pink tent dress, she was a perpetual struggle of flesh, heaving with every breath. Limbs that were separate from her but also a part of her were forever uncomfortable even though she adorned them in tattoo sleeves of fuschia, green, and marigold. Each arm was a magnificent canvas covered in floral intricacy. Lois matched them with a single rose lacquered barrette holding back a sweep of hair on her right side. Absent-mindedly checking on it to make sure it was in place. It wasn’t the only delicate thing about her.

She liked the smell of a clean bar, wiped with a freshly wet towel. It glistened in cherry streaks and then dried in patches according to soft grooves in the ancient wood. She would wipe and watch it dry, like wet paint on canvas, closely following the streaks and puddles. Close to her thighs, the shapely bottles in the well shimmered with condensation making them harder to handle as she rearranged them to her preferred pouring habits. It was nine o’clock.

At half past nine, the old lady in the front slumped over and landed with a thud on the floor. A sound that was echoed by a large RV struggling to make the overhead clearance under the nearby interstate on-ramp. By this time, thirsty men had streamed in and filled up most of the stools at the bar. Further down, a disjointed melody permeated the space between talk and demands yelled across at the reluctant bartender. Narrow and dirty, the singer’s small space was carved out in the bar’s rear, in front of the only bathroom, near a defunct jukebox. A naked and glowing yellow bulb swung down to illuminate his angelic face, leaning over a tired acoustic guitar. His dark bangs shielded sloppy eyeliner and blue eyes.

Lois started to feel her left foot throb, reminding her to shift her weight to the right, which immediately caused her right foot to throb, she sighed.

“Jerry, grab the damn drink with your good hand before you spill it all and I gotta clean it up,” Lois’ wide face contained a sarcastic spread of cheeks and lips.

“Gee, Lois, it ain’t gonna be no fun to come here if you’re heavy on my drinkin’ style,” Jerry, younger than the others, was easy to recognize because one of his arms was considerably shorter with two unsightly limp protrusions sticking out of it. After about three drinks, Jerry attempted to exercise these pathetic excuses for fingers by picking up a shot glass. It never worked.

“Lois, where’s Dusty? You giv’er the broom again?” Jerry was smitten with this well-timed comment especially on the heels of his childish response. He sat a little taller when the old boys around him snickered.

Where was Dusty? Lois turned her massive head to the right, tracing along the rail length of bar, stools, and drunks on stools. She peered into the dark front space. Old wooden tables and chairs usually secluded a quiet couple. Dusty’s favorite lean-to area was empty. Didn’t she remember her there when the night got started? Lois thought it’s not like she had anywhere to go, though sometimes she went walking, sweeping through the streets before closing time. It was only ten o’clock.

sidewalks clean now of me and my worries Mom always said I’d worry myself to death and here I am a quiet uncomfortable lump working through time unordinary better than I would have imagined just a month ago long and loud those interstate trucks tumbling—enough to make me quit it all but for him I hear him now wandering —times wondering it all over ‘bout me and my —but not him he’s gone already and isn’t that his fresh shirt I smell—- and him singing me ‘sleep, oh him!

Jerry felt exceptionally proud of his two feet when he planted them on the dirty bar floor. He didn’t know much about anything else. Except he did care when it seemed the angelic face framed by shiny hair stared up at him. It was a circuitous wondering that often followed him into drunken dreams –fantasies really. In his head he said how are you tonight ‘tonia. In reality he said: “Can you make room? Gotta make it over there.” The angel nodded, and the slight relational ambiguity off-putted Jerry so much that he stumbled, made an awful face, and reached out with his shitty arm to push in the bathroom door which slammed back in his face before he got through. Was it Tony or Tonia? his thoughts fumed.

Tony was a weekend regular. He was proud of his bangs and practiced pout, but the guitar was an act. Rent had increased by a hundred in the past month and he knew it would be tight without extra money. He preferred bass. On Saturdays, Lois let him play and drink. The bangs, the lips, the fishnets under jean shorts were a costume. He thought how easy it was to convince imbeciles of femininity with crossed legs, false lashes, and a demure nod.

For three months, he had played the weekend nine to one crowd. Managing drunk customers and righteous gropers wasn’t half as bad as learning new covers to fake. By eleven, he could mutter the music without a glance his way. What was special, what almost made the scourge tolerable, was Dusty. After twelve, Dusty would stumble (why was she always stumbling? She never had a drink in her hand), sat in the closest stool, closed her eyes and hummed along. No melody ever escaped her. Old or new, she would breathe new meaning into each song as if performing it for a small audience inside her head. An old, muttering woman to most, to Tony she was the only one that seemed to hear his music.

Where was she today? I thought I saw her come in. Tony removed the old strap from over his head and leaned the guitar down by the side of his folding chair. He planned on sneaking into the bathroom for a puff. But just as he stood up a whiff of urinal cake hit him in the face. Feigning an impromptu stretch, he sat back down and crossed his legs. Jerry, with his hand on the open door, followed up the repulsive scent. He was wiping his stub on his shirt and scrunching his face in a drunken grin. He had given himself a pep talk while taking a piss. He leaned into Tony’s face with a snicker.

“Hey Angel-face,” Jerry decided this was the way to handle the fact that he couldn’t remember her name. You know, make it her responsibility to advertise. She didn’t seem to understand the rules. She just stared up at him, her cupid mouth twisted in a tight bow.

“yes,” was the underwhelmed response.

“Ne’ermind,” Jerry’s problem was that he always gave up when anything became a challenge. It was eleven o’clock.

When “angel-face” recalled the last time he saw Dusty, it was about a week ago. He remembered the smell of cinnamon and sulfur. Dusty had made her midnight move from front of the house to the rear, sitting on an open stool, hunched and haunting. There were never any words exchanged between the two. Instead, reciprocal moods scribbled their way like crayons in the hands of a young child –a little violent, a little exhilarating. Tony had smiled. Dusty had muttered. Something indistinguishable –a compliment, maybe? It was a strange exchange.

Meanwhile, the regulars were a silent chorus of desperation and decay. Together, it was a weird party. Attendant barflys alternated between a hunched beer stare and a straight one arm swig in uncanny regularity. Synchronized in their pantomime movements. Human? Yes, but measured by one line requests. Their individual lives amounted to a collective need parsed in transactional vocabulary.

“Pour me ‘nother Lois, willya?”

“Jst use the old glass, I dn’tcar.”

“Same, that was the Rainier, clear the head.”

“Shot of Beam, one for my buddy.”

“Lois, howabout that beer, heh?

“‘Nother, yep, same s’fore.”

“Lois, you’re looking good, I likeya in pink.”

“Whit, she’s wearing a goddam tent, what you about??”

“Just a shot of Jack and a separate Coke, kay?”

not ready i’m not ready who ever is though some say so ‘dvertise it in fact i’m not going not ready –not ready who ever is to leave even this it’s still somethin’ its not nothin –oh him, he’ll be along my him my song does it end or begin with or without how did it ever –him without me is an end i’ll sing–

Tony remembered Dusty. He remembered that Dusty seemed immune to her surroundings. Sitting on a shadowy stool, unable to unhunch her shoulders, her hanged head would heave toward the sound of music. The last time he saw her, in between one of his sets he sat watching her intently. Despite her broken face, he detected something, passion maybe. Not the kind that bristles like static. No, not performative, perpetual and aching like a celestial being caught and locked in a human body. Dusty’s eminence was evident in the glint of silver on her wrist –ocean blue flecks of white– were these the colors of love, Tony had wondered. Her matted hair, flat yellow and sickly, a paper color like her skin. Thin lips and slack jaws hung from her skeletal face. She wavered between dimensions, outlined in red and blue ebony, she was a gilded angel cut from the softest paper.

Leaning with one faded shoe on the floor, one bony leg propped on the pedestal. Both arms bent on the bar bearing the weight of her lean body. Dusty had begun to hum along to one of his poor performances. It seemed she might tip over. It seemed difficult for her to breathe. Her body was so fragile but the sound he heard was a sustaining force. It had seeped into his music, thread and bound together his own breathing to resonating chords. He strained to hear and understand the nature of it.

Did Tony see her?

Her body was lying on the dirty floor in the front of the bar. Her ascent was happening in the back of the bar, lifting up, forgiving the shitty notes of the cross-dressing guitar player.

It wasn’t twelve. Reaching down to grab his guitar, unaware of Jerry’s scrutiny, Tony sighed. In the space of a minute he had become an old man tired of his offspring. Lois was roping in the regulars, offering shots. Turning away, Jerry attempted to wipe off his personal space with his sad stump. Dusty was nowhere. Street lights became orange and puce refracting sharp Kandinsky flecks of modern potential across the rutty worn wood. Grim and drab, the chorus was looking for spent wishes at the bottom of their empty glasses. The bar would be replaced by spit and cardboard condos in a year.

No bar should ever be this silent, thought Lois turning toward the rear and wondering what happened to the damn music.

“Tony, whatcha playing?” she asked toward the back of the bar without really trying to bring into focus the pale face caught up in his own reverie. Tony, jolted out of the lulling hum that had interrupted his set, was muttering. He couldn’t shake the feeling that his thoughts were not his own. Oh him! Looking up, he confirmed Lois’ wish with a slow nod, not entirely certain how to proceed. Instead of picking up his guitar, he tilted his pale face toward the naked light, clasped his too-large hands close to his heart and opened his mouth.

When a clear note pierced the noise the entire bar turned in his direction. They were shocked into emotions several had sworn off years ago. Lois’ reaction was simple amazement, holding a wet towel in her big hands she found herself squeezing it so hard that drops of water dripped on her clammy toes. Jerry, having given up on his cleaning effort, found the urge to spin his stool and when he registered its fixed state he turned his whole body and propped himself with one foot on the floor, his butt teetering on the edge.

Tony’s eyes were closed while his lips parted in peculiar triumph. Even the beer ears registered its magnificence, climbing from a bass into a breathy soprano. A narrow stroke, up and up, trilling, constant, piercing and clear. Eclipsing a sound that had originated in heaven.

Looking down on her progeny, Dusty decided to grant Tony something he never asked for –perfect pitch. Just then, he hits a note that threatens to shatter the naked bulb above his head. Some noticed him for the first time that night. They hear an innocent voice singing in a church choir, they hear the call of a lonely angel whistling to her sisters. A thread of purest gold, fine as an infant’s first curl –a shimmering tendril tickling their inner ear.

It was not a song, but each person in the bar heard and interpreted it based on individual experiences with grief, remorse, of life and death. One old man who only ever said enough to place an order, heard his dead wife’s voice singing a lullaby to their newborn child. Jerry heard his best friend ask him for the keys before getting into a wreck. Lois heard a beloved mewling from feral cats her mother used to feed when she was young. Tony could not hear himself except for the suggestion of gentle fingers cradling his head as if he were waiting to be kissed.

The room hummed in a symphony of end of night energy. Clinking glasses shoved into plastic slots of a wash tray. Abounding from quiet the note that had paralyzed them was shrugged off –yet remained, in their bones, in their minds, hidden for safe-keeping. Tony was himself again. In his heart lingered a reverberating promise of possibility that caused a momentum he couldn’t resist. He started to pack up his amp and guitar.

“Hey, it’s not one yet, watcha doin’?” Lois projected her voice toward the dim single light and pale face under it. The face smiled sheepishly and shrugged. Lois was mistaken, the face seemed more confident now than it had ever been. She set the glass she was holding down with hard authority.

“Tony! What the hell’re ya doin’?”

“I’m done for the night. Nah, maybe forever.” Tony, having packed up his gear, bumped his head on the above light and looked garish to Jerry who never realized how tall she was. Tony’s final performance was to quietly walk past behind the drunks on stools with eyes on the heavy door that separated the stagnant and thick air of the ancient bar from the crisp promise of a hopeful world.

If not for his important exit, he would have seen the ghostly mass behind a wooden table. He would have seen shiny silver against the dark floor. He would have recognized how out of place it was. Instead, moving now to escape what had always been a regret, he kept his eyes forward, on the door, measuring the amount of strength it would take to open it without hesitating.

Jerry kept his eyes on Tony’s ass, thinking it was skinnier and more muscular than he preferred.

III.

Poor leftovers were scraped up by those who hung on to the fading night. Jerry was certainly one of the burning remains, haunting the bar as Lois attempted to tidy up glass, spills, and wet towels. She never checked the front, it was untouched.

“Jerry, thanks for waitin’ but you didn’t have to, ya know?” Lois acknowledged, finally, that this absurdity of a man was going to try his best to go home with her tonight. She was intrigued. What seemed an impossibility in the beginning of the evening was easily a temptation by night’s end. When she saw him holding the door she decided that he had landed himself a sure thing.

“Thank you kindly,” she nodded pleasantly enough to stay him, “but I gotta count the register and put it in the safe.” Lois smiled at her reflection in the bar mirror, watching Jerry shrug and release the front door. He took a heavy chair from one of the front tables and sat as if a reluctant matinee usher.

“It’ll take a minute,” she felt the need to respond to his chivalry.

“No hurry,” was his response. Jerry racked his brain for something clever to say, but gave up when all he could think of was my darling. It seemed too much a commitment for a late night bet.

“Lois, ya think Dusty lives ‘round here?” He decided to change course, instantly regretting the topic. All the same, he was curious –not concerned.

“Wha? Why ya bringin’ her up?” Lois retorted, “Ya interested?”

She smiled again at herself in the mirror, deciding finally that stripping Jerry of his guile might be better than getting laid.

“Wha!? Naw, of course not! What! You messin. I was thinkin’ is all about if she lived close by.” Jerry really started thinking about it and the more he thought about it the more he started to feel sad about where he lived and why he was sitting in an uncomfortable chair, waiting for a truck of a woman to take him home for uncertain pleasure.

Lois locked up the safe and walked out from behind the bar. She took one sweeping look around. No strays, no empty glasses, no lights.

“Alright, let’s go,” she glanced down at Jerry, who was lost in his temporary humanity. When finally he looked up innocent and hopeful, she felt sorry for him.

“Dusty don’t live no where Jerry. You know that. You know that already.”

“I was just thinking maybe she stayed home tonight, ya know with folks, her folk.”

The pounding of Lois’ heart was in her chest, but she could hear it in her ears, and briefly she wondered if the moon was full or something. Why is everybody actin’ so weird? She looked down at Jerry. His good arm was cradling his sorry stub. He stood up and was shorter than her, by a lot.

“Thanks for waiting for me. I gott’n early mornin’,” she pulled the gate shut on the bar door, and seeing an unrecognizable shimmer through the dirty window made a mental note to call the owner who opened up on Sunday afternoons.

Jerry was stuck, confused and distracted. He was also a little drunk though granted a taste of fleeting sobriety that comes with stepping out of a closed space into the open night. There, under one of the city lights he watched a poor figure stumble toward them. Lois saw it too.

“Yeah, I’ll head home I guess. See you later,” said Jerry. He already had his back to Lois when he started walking opposite the oncoming silhouette. He reached into his pocket to feel for keys. He tried to remember if he drove. He thought, if I drove where’d I’ve parked?

Lois watched him walk away, smitten at his meek attempts, a touch insulted that he gave up so easily.

“Scuze’m mam but ya see Dusty here?” The man’s speech was slurred, he did not make eye contact. He had a gray face, pale lips, and dark hair. He was very tall. Hunched as if to generate momentum in a direction; so much so, his body did not seem his own, yet he propelled it.

Lois had never seen this man in her life and was again miffed by Jerry walking away and leaving her exposed. Thanks a lot, she thought while trying to assess the danger.

“I know Dusty, she comes here. I dunnit see her tonight, sorry.” Lois decided to keep it short. It was always safer to be respectful but curt when approached by bums.

The man’s eyes widened exposing confusion and dismay, fear and despair, hopelessness and acceptance.

“Thanks, if yaseeher letta ‘er know, Joels lookin fer her, thanks.”

“Sure, I will. No probem,” Lois turned, pretending to fiddle with the gate so the stranger would get the hint. When finally out of the corner of her eye she saw him shuffle down the road, she turned in the opposite direction thinking about what kind of mess her cats made of her apartment. The dim streetlamp buzzed and popped while her own heavy footsteps echoed into the vacancies of the night.