My aching heart, her aching heart, like the faithful dog that has fought the good fight for the loyal master only to be surrendered for an energetic pup.

Staring out the glass door, a long stare. Too long? Fearful? Are you perplexed? Your son suddenly shows up in the driveway as you make your great escape. Kooky, eh? Weighing your options? Are you man enough to walk out here and confront me? Unlike Houdini, you can’t control your environment.

Man enough? That’s a slippery term. Man enough is what pushed you here. You’re man enough to leave your wife of 30 years, leave you family, so you can start fresh with a younger woman. That’s a man? Right, right, that’s what Real Men think. A hookup? A hookup is just casual sex, but you are cutting your family loose. That ain’t a hookup. Not one thing about leaving your family is casual.

Walked away now. Take a leak? Grab a bite? Maybe give your lover a quick ring, let her know your son has you pinned in, like a hog waiting for slaughter.

Is that what Real Men do? Do you really want to rain on her parade? This is your family, your battle, your war. She’s a show pony, the soon-to-be trophy wife. I guess sometimes a Real Man has got to do what a Real Man has got to do, which for you, Mr. Real Man, is leaving your wife and family. So what if your partner of 30 years devoted her life to you and your children? It’s a Woman’s Job, right? What is a woman to you? A cross between an adult and a child? A tool for a Real Man to use, just the way the world works. For good or ill. You didn’t make the rules, you’re just playing the game. She followed the Woman’s Job Handbook, be the maid then you will be taken care of for life, the promised land of marital bliss. The pearly gates of happily-ever-after. Complete self-sacrifice. The true martyr of humanity. Where’s my calculator? Okay, over 700 meals a year for 30 years…holy moly, Batman, that’s 21,000 meals. That’s in the Betty Crocker range. I wouldn’t blame Mom if she hit you over the head with a frying pan. And the laundry? Let’s not even get into that. The dishes, the vacuuming. Measure all that work and sacrifice against a sexual carrot. Not much of a decision for you, Mr. Real Man?

Steady as a rock? Who cares? Not you, Mr. Real Man. Dependable, would walk into a wall of flames for you. Tell somebody who gives a damn, right? Real Men know that a woman’s job is dust in the air, can toss like a disposable lighter, time for that shiny one. Gotten all the goody out of this one, eh? Can’t worry about the way she feels, open that door and in walks guilt. “I don’t know what to do, Danny. I’ve tried everything. I just, just don’t know what to do.”

“Have you tried talking it out with him?”

“He won’t even talk to me. He comes home late at night and leaves early in the morning. He’s sleeping in the front bedroom now. That woman calls when he’s here and they talk for hours. She’s married, too, you know.”

Nada, nothing, didn’t feel a thing, walking out requires Novocaine. Heart? A black heart. Was it always there, just buried deep, ready to raise its ugly head? But you always had the look, hard to fake, genuine sincerity seems difficult to muster if the sentiment isn’t there. Jekyll and Hyde? Maybe that’s part of being a Real Man.

Another look, Howdy! Now that’s a so-happy-you-came-here-know-you-know-my-name look. That fear has flipped to smug. Show pony courage?

Do you truly not consider the years of wading through the rough and tumble experiences of marriage? The arguments, the conflicts that are inevitable when two people live together. Like every relationship in the history of the world, you two took your jabs at one another. Mom flat refused to help you establish your own copy business, and you were like a speed freak with your obsession to run for city council. Bad times. So what? Push on, right? You were making it through the mine fields. Big lottery winning smiles of pride at your own ticker-tape parade.

It’s what the guy at the top of the mountain will tell you when you ask him, “What’s the point?” That’s what I want. That’s what we all want. Right?

So why walk off the field in the seventh inning, at the end of the third quarter? Are you tired of playing on this team? You’ve decided to initiate your own trade, try to get on a younger team, one that excites you. Well, I’ve got bad news, the team will not let you go, a teammate has grabbed you by the collar. Some things are worth fighting for, right?

A rooster crowed from the passenger seat.

“Hey, Lauren. What’s up?”

“Hey, Danny. Whatcha up to? I was just thinking about you. You busy tonight? Want to come over?”

“I’d love to, but I can’t. I’m in Huntsville sitting in my parents’ driveway.”

“Huntsville? I was thinking we’d grab a pitcher at Harry’s.”

“You love that place, don’t you?”

“Dive bars are kinda my thing.”

“Drink a few for me. I’m here on a mission. Looks like my parents are splitting up. Caught my dad loading his shit in his trunk. He’s bailing on his family, nightmare city.”

“Even your dad is a member of the piece-of-shit men’s club? What the living fuck. Man, I’m sorry to hear that. You’ve never mentioned anything about your parents splitting up.”

“Not something I like to talk about.”

“I get that. How long have they been together?”

“Over 30 years. I thought if you made it to 30 years then divorce was off the table.”

“I don’t think there’s an expiration date on that. Another woman?”

“Of course. A midlife crisis. A walking cliché.”

“Damn.”

“I know. He’s in the house right now, taking peeks at me. Looks like it’s gonna be showdown, will try to talk some sense into him.”

“Gonna get ugly?”

“Sure of it.”

“Good luck. Don’t be afraid to open a can of whupass if needed.”

“Will use all the tools at my disposal.”

“When you coming back?”

“Probably Sunday. Hey, let’s do get together. I haven’t seen you in a while. You still seeing Ross?”

“Fuck Ross. Narcissism personified.”

“True that. I told you.”

“He’s a good lay.”

“Sex is like a good margarita, lots of fun but you can’t live off it.”

“Ha! You can tell me all about the gunfight next week. I’ll give you a ring.”

“Sounds good.”

“Be careful, cornered dogs can be mean. See you, Danny.”

“Later, sweet girl.”

Ahhhhh, another look, this time out the window. Hello, yes, I’m still here.

Wait a minute, I’ve got an idea. Why don’t we take a drive down to Tony’s Tattoo Parlor. Tony’s a good guy; he’s the one who put that tattoo you don’t know about in the middle of my right ass cheek. When I told him I wanted just the words, “Life’s Good,” he tilted his head back and let out a moan of a laugh. “Ain’t it though,” he said. Tony’s a smart guy, did a helluva job, too. Cursive letters, a clear deep blue. “I usually charge extra for cursive, but this beats the hell out of another damn Confederate flag.”

I’ll drag you to Tony’s little shop, sit you down in his barber’s chair, then have him put a nice scarlet “A” right on your forehead. Dead center. Oh, you’ll be the envy of all your friends. But an “A” would be too traditional. You’re a leader, not a follower. Time to forge new ground, enter uncharted waters. After all, you are an adventurous man, a Real Man. Yes, I’ve got the perfect tattoo. A nice scarlet penis right on the forehead. Oh, my, the choices in life are what makes this ride so damn fun.

Let’s spice this up a little bit. How about I get out and lean against your escapemobile. Just to let you know that I’m not going to drive off. I’m turning up the heat, Mr. Real Man, see if I can make you sweat, make you squirm.

Ahhh, a nice afternoon. Yes, indeedy, a nice fall afternoon for a philandering husband to be beaten with shame by his twenty-two-year-old son. Irony much? The soothing peace of a fall afternoon in Huntsville, Alabama, providing a beautiful setting for a husband and father to blowup his family. There’s something in the air. Is it truth? Nonsense. Only shallow sentimental movies and weak people reveal lives of such failure. Maybe that’s the nut of it. Life really is a soap opera. Maybe Oscar Wilde was right, “Everything in the world is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power.”

Perhaps Carla was right last night when she tried to pump me up for my save the family extravaganza. She said you’re just running from yourself. She said you’re hanging on with a vise-like grip to the image of your youth. Your mortality is wearing you out like the July sun bearing down on a roofer. Find a younger lover so you can pretend like you’ve still got life by the tail. You’ve been passed over for a few promotions, youth grabbing what should have been yours. You think you’re the first? The youth movement. Yesterday’s news. You’re fifty-two years old, raised three kids, worked like a Trojan, but now you feel like you’ve lost your purpose. What mountains are ahead? What now, indeed.

Maybe the obvious is the obvious. A loving and devoted father and husband with a heart so big you nearly crumbled watching Frankie slowly dying in the garage. He moaned and whimpered, glassy eyes, shudders of pain. Even then he gave us both a loving look. Clone that son of a bitch and give him to everyone. Have Congress create a National Frankie Day. Released violent offenders will be given twenty dollars, a new pack of underwear, and their own freshly cloned Frankie. I stayed with him after you went back to bed, but right before daybreak you walked into the garage, crouched down on your knees to give Frankie a close look. Then you turned to me, “Danny, we’re all going to miss him. I wish he could live forever.” That was one of those moments you want to freeze-dry so you can put it on your coffee table, look at it every day to remind yourself that the best hearts are what make life worth living.

You loved us, that’s a fact. You can just walk away? What am I supposed to do? Build up a wall, paint it with cynicism, then carry on with life?

Another rooster crowed from the passenger seat. I walked back to my car and grabbed the phone.

“Hey, Carla.”

“Hey, baby. Are you at your parents’ house?”

“Yep, I’m here, standing out in the driveway as I speak. He’s packing up the trunk.”

“He’s packing? Are you surprised? Have you talked to him yet?”

“Nope, no surprise here. He hasn’t come out of the house since I pulled up behind his car. I’ve caught him giving me a few looks.”

“I guess he doesn’t want to confront you.”

“He walked up to the front door a few minutes ago. Then slithered away. I would think he’s drowning in guilt right now. Or maybe not.”

“Are you going to tell him off? Might not be a good idea.”

“I really don’t know. I’m a little nervous, all juiced up, like they’re slipping on my gloves in the dressing room before I enter the ring.”

“Just don’t get too angry. That’ll work against you.”

“Honestly, I feel like getting in my car and driving back to Tuscaloosa.”

“Don’t do that, you’re already there. I think you would regret that.”

“Na, I’m staying.”

“Hope all goes well.”

“Me, too.”

“Are we still on for next weekend?”

“What?”

“Going to my parents’ place in Dothan. Remember?”

“Right, yeah, okay, maybe.”

“My mom and dad are going to be disappointed if you don’t come. They’re really looking forward to meeting you.”

“I know but—Kaboom, Elvis has left the building.”

“What?”

“My dad just walked out the front door.”

“Oh, wow, okay.”

“Things are about to get real.”

“Be strong, Danny.”

“I’ll talk to you later.”

Finally got up the courage, eh? Lock and load. Time for the shoot-out. Clear the women and children. Is that a look of sadness? A little late for sympathy. Time to meet your maker. You can’t say you’re sorry then ride off into the sunset. Not gonna happen, Bronco Billy. Didn’t plan on this confrontation? Come on, big boy. Let’s get it on. Time to see Tony.

“I didn’t expect you home this weekend, Danny,” my dad said as he walked up to within a few feet of me.

“What are you doing, Dad?”

“Danny, let’s don’t get into this now.”

“When are we supposed to get into it? On your deathbed?”

“You know your mother and I haven’t been getting along for a long time.”

“So, you’re going to throw away 30 years of being together because y’all aren’t getting along right now? Fuck, Dad, nobody gets along all the time. That’s bullshit.”

“We can talk about this if you want, but I can tell you’re very emotional, you’re angry. Do you really think you can talk about this with the way you’re feeling?”

“I can if you’ll be honest with me and not give me the ‘we’re not getting along’ speech.”

“O.K., I’m willing to discuss it, try to explain to you why I’m leaving. You’re my son and I want you to understand. I know you’re thinking I’m leaving you and your sisters, too. But that’s just not true.”

“But Dad, you–.”

He raised his hand and cut me off. “Before we get into it let’s at least go inside so we don’t let Donna next door hear every detail. I swear that damn woman knows things about the family before I do. She’s probably bugged our house.”

I laughed out loud, which was good since my heart was beating like a hummingbird. We walked to the front door with Dad’s left arm around my shoulders.

After entering the house, he said, “Why don’t you go on back to the den. I’ll get us a drink. What’ll you have?”

“Whiskey, neat.”

My dad arched his eyebrows.

“Better bring the bottle.”

As I walked to the back of the house, to the den my dad added on several years ago, I wondered if drinking was such a good idea. If I got drunk there was no telling where this might go. About a minute later Dad walked into the den carrying two whiskey tumblers, and a bottle of George Dickel. He poured two fingers in each.

“To life,” he said.

I nodded my head, “To the death of our family.” I clinked our glasses together.

He grimaced and brought the glass to his lips, taking a deep swig.

“Mmmmm, that’s smooth.”

“Smooth as fire.”

“Where do you want to start?” he asked.

“How about with why.”

“Why?” He slowly shook his head while looking at the ceiling. “There isn’t an easy answer to that. Whatever I say won’t satisfy you. We don’t see eye to eye on much anything, anymore. Raising you and your sisters probably kept us together the last few years.”

He looked at me hard. I didn’t say anything for several seconds; I was thinking about their relationship.

“You’re just going to throw away thirty years?”

“It’s not that simple, son. I just can’t go on living like this.”

“Like what?”

“Like living a lie. We’re very different people now. There’s a whole slew of reasons why we don’t fit anymore, different interests, friends, what we want out of life. All kinds of things.”

“But you’re just flushing our family down the toilet. You’re walking out on us.”

My dad turned up his glass and finished off his whiskey. He set the glass down on the table and poured himself a couple more inches. I took another sip of mine. He shifted in his seat, raised his hands to me as if he was showing me the length of a seven-pound bass he had caught last weekend.

“Now listen to me. This is extremely important. You, and your sisters,” he moved his hands in a chopping fashion, in sync, like an invisible rod ran through the center of his palms, “will always be a part of my life. And I want to always be a part of your lives. This home will not be the same, obviously. But y’all are young adults now. It’ll never be the same like when you were kids. Those days are just memories. I think part of your reaction stems from growing up. Your mother and I tried to give you kids a good home. It’s tough letting go of those years.”

Dad dropped his hands.

“Most of our decisions were based on what we thought was best for y’all. And I know you’ll always be able to come to either one of us. I wish everything had worked out between me and your mother. I really do. But it didn’t. That’s the short and simple of it.”

“What about Mom? Don’t you know this is going to kill her?”

“Now Danny–”

“No.” I stood up, walked to the other side of the coffee table, and faced him. “I don’t think you’re looking at this right. You’ve invested over 30 years of your life in this family. You’ve always told me to think things through. Well, I don’t think you’re thinking this through. You’re just thinking about yourself. You’re being selfish. Leaving is going to turn our lives upside down. I can’t let you do this.”

“I was afraid this would happen. You’re too angry to discuss this.”

“I am not too fucking angry.”

“You’re acting like a child. What’s happening would be devastating to a ten-year-old, but you’re not a ten-year-old.”

“I’m acting like a ten-year-old? Oh, that’s great. Not only are you walking out but you’re calling me a child. Tell me if a ten-year-old would do this.”

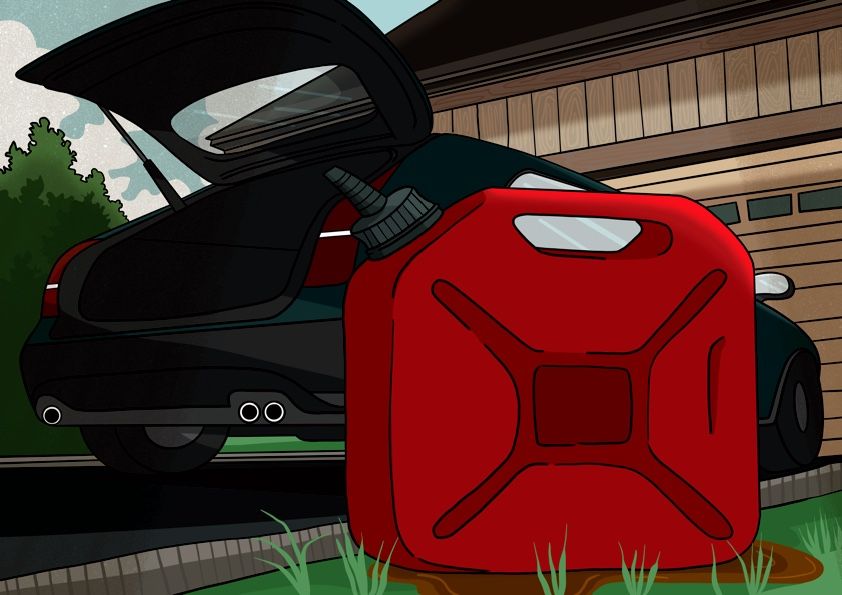

I looked at my father as I walked out of the den and saw him eye his drink as he said, “Please, son.” I walked into the kitchen, through the side door to the garage, over to the mower sitting in the corner with the rakes and shovels, grabbed the gas can and walked out the back door. Taking quick long steps, I rounded the side of the house and stalked up to his car. I unscrewed the cap and began pouring gas over his clothes, duffle bag, a TV. The one-gallon container was less than half full so the gas emptied from the can in just a few seconds. As I walked to my car, I heaved the can towards the front door. It hit the wall just to the right of the door then banged onto the front steps. Reaching through my driver’s window I pulled a purple lighter from the passenger’s seat, floated back to the open trunk, but before I flicked the cylinder, I noticed my dad standing behind the glass storm door. Our eyes locked. I wanted him to run out and try to stop me so I could drive my fist into the side of his face. But he didn’t move. He just looked at me. Motionless. Expressionless. As I bent over the lid of the trunk with my thumb on the cylinder, I heard a noise behind me. I turned and saw a little boy in a cub scout uniform carrying a small white cardboard box walking up the driveway with a young woman. The woman stopped at my car, but the boy loped right up to me.

“Hi,” he said with a smile and a wave.

“Hi.”

“I’m selling chocolate bars for my cub scout den. They’re five dollars each. Would you like to buy one? I’ve got milk chocolate and another with peanuts.”

The boy sniffed, looked at my dad’s car, then at the lighter in my hand.

“I smell gas. You know you shouldn’t play with gas.”

Looking back at the mother, I saw a look of worry. Then I recognized the woman, the older sister of a high school friend.

“Are you Tia White?”

“Danny Thorn, I thought that was you.”

“How are you doing, Tia?”

“Doing good. Paula was just talking about you.”

“How is she? I heard she moved to Atlanta.”

“She just started a new job, seems to be happy. That’s all you can hope for, right?”

“True. Is this your son?”

“Yes, this is Patrick.”

“Well, hello, Patrick.”

“Hi.”

“Wow, you have a kid. That’s great. You’re a pretty big boy.”

“I’m six.”

“That’s a good age. Lots to love about six. Hey, did you end up marrying Dennis Fennel, Tia? You two were all into each other in high school.”

“Yes,” she said but the smile slid from her face.

“Patrick here looks just like Dennis.”

“Dennis died a couple of months ago.”

“What?”

“He tried to save a couple kids who got pulled out by a riptide down in Panama City. All three of them drowned.”

“Oh my god, I’m so sorry, Tia. That ain’t right.”

“It’s been tough,” she said as she looked at her son, “but Dennis died a hero. Right, Patrick?”

He nodded his head. “It’s funny about gas.”

“What’s that?”

“I know it’s not good for you, but I love to smell it.”

“Yeah, I remember that,” I said.

I stood looking at the boy for a few seconds. He looked at the trunk, raised his hand and pointed, then looked up to me.

“Did someone pour gas in your trunk?” he asked.

“Yeah, I’m afraid someone did.” I looked back at Tia. She looked even more worried than before.

“Come on, Patrick. We need to knock on a couple more doors then head home for supper.”

“Wait,” I said. I reached in my pocket and pulled out a five-dollar bill. “I’ll take one of those chocolate bars.”

“Yesss,” said Patrick as he clinched and pumped his right fist. “Do you want plain or peanut?”

He took the money and opened his box of candy bars.

“I think today is absolutely a day for peanuts.” Patrick handed me the chocolate bar.

“Thanks for your support. See ya,” then he turned and walked back down the driveway.

“Bye, Danny,” said Tia as the boy passed her. She stared into my eyes, glanced at the trunk, and gave me one more quick look before she turned and followed her son. I tried to interpret her look, sadness, embarrassment, or unease, but I felt frozen in the moment as she walked away with her son.

“I’ll see you later, Tia.”

I watched them walk to the sidewalk then take a right, both giving glances back at me and the cars. As they walked down the street, I noticed the shadows from the trees crawling across my parents’ yard and house. The crickets were beginning their song. I turned back and looked at my father who was still standing at the glass door. We stared at each other for several moments. That scent of the flammable perfume filled the air. I tossed the lighter and the chocolate bar into the trunk then began the slow walk to the front door.