The world is warm and wet. Sunlight sears the back of my neck, and water seeps out of the ground, invading the foam soles of my flip flops. I break into a brisk trot, trying to outrun the seepage as much as I am trying to catch up with the other children as they stream into Mary’s basement.

I’m not sure why she invited me to her birthday party. I was under the impression that she didn’t like me that much. Rejoining the pack, I brush past Mary as I cross the veil from the steamy outside to her cool, air-conditioned basement. She smiles at me without teeth, and I begin to wonder if I’ve done something wrong, missed some sort of social cue. Perhaps I should not have worn cargo shorts.

Mary herds us up two flights of stairs to her bedroom, past her father’s massive flatscreen and her mother’s white Ethan Allen sofa. The room is large and pink, much larger and much pinker than my bedroom, but still too small to handle the number of partygoers now worming into it, our skin so tacky with sweat that we stick together when we touch. My knuckles accidentally brush a girl’s thigh, just beneath her shorts’ hem. Ashamed, I shove my hands into my pockets.

Some of us spill out onto her balcony—I didn’t even know people could have balconies in their bedrooms.

I notice the little black shape clambering up the downspout, recognize it, and turn my attention elsewhere. I have to keep up with the conversation and tell the right jokes at the perfect time to make them all laugh, or they’ll throw me off the balcony.

Mary blesses us with her presence, coos with the other girls while I stand awkwardly in the background, chipping at a flaking bit of paint on the railing. One of the girls sees the little black shape, but it’s Mary who screams.

Suddenly, I’m the center of attention as they all scramble behind me.

“It’s just a daddy-longlegs,” I say, confused. The spider creeps off the downspout and onto the white siding, its delicate limbs tentatively feeling along its new path.

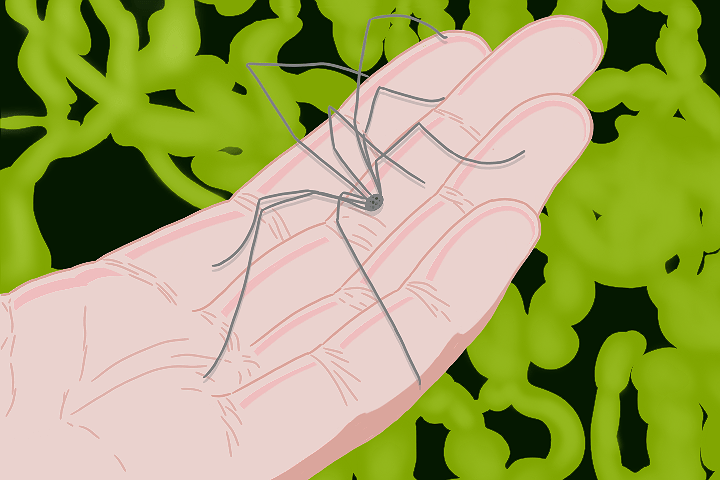

My father had introduced them to me, plucking one off a tree and setting it in his palm. He let it crawl on him, its legs blending in with his dark hair as it meandered across the back of his hand.

“They’re harmless, see?” he’d said. “So never kill them.” He put the spider back down, and it skittered away.

“Kill it!” Mary screeches, tugging at my sleeve.

I crane my neck to look at her over my shoulder. “But they don’t bite.”

“I don’t care! Kill it!”

Swallowing, I turn my eyes back to the daddy-longlegs. I’d already given Mary her gift—a pair of strawberry earrings from Claire’s—but now she wants something else. Bending down, I slip off my blue flip flop and hold it in my hands.

“Come on!” Little fingers hook into me, tearing at my shirt and back and arms. “Do it!”

Tears well up in my eyes and I blink fast, trying to outrun them. Bursting into tears is not very “birthday spirit,” not very “cool kid” of me.

I raise my arm, the flip flop casting a broad shadow on the spider. Run away, I pray. Move, please. I don’t want to be responsible for its death, but I don’t want to be responsible for saying no, either. The spider continues to crawl and explore, ignorant of me in a way I wish I could be ignorant of it. In my mind I call it “him,” because he is too much a person to me to continue on as “it.”

I know what I’m about to do is wrong. Chewing on my lips, eating off the sunscreen my mother had forced me to put on, I wonder if the hesitation makes me more evil, more of a coward. I want to go home.

It’s over quickly. The scene ends and the actors file off the stage and back into Mary’s explosively pink room, leaving me alone with the black smear on the sole of my flip flop.

The sun slides like an egg yolk down the clear, blue sky, and I know I must rejoin the group. I must make the price I’ve paid worth it. The balcony slats are rough on the bottom of my foot, my hips shifted unevenly by a matter of centimeters. Inside, I can hear the other children laughing. Later, I will get so good at plastering on a smile that I won’t be able to stop, but now my face remains lax, and I go somewhere else.

By the time I return to myself, I am standing in Mary’s basement next to her older brothers’ candy machines, the kind that were only supposed to be in stores. Candy is forbidden in my house. I pull the handle and collect a handful of rainbow dots, the food dye coming off on my palm, and shove them in my mouth.

As the Skittles tingle on my tongue, I watch Mary blow out a pink candle shaped like the number six. Everyone cheers, and she looks up, smiling at me with teeth.

———

I open the freezer and make eye-contact with the worm at the bottom of the Monte Alban bottle. It’s not actually a worm, but a larval moth—gusano de maguey. My ex told me about it, said he drank it when he went home to Mexico and that the worm tasted like nothing.

My upper lip curls back from my teeth, exposing my gums. I think of taking the bottle by its neck, throttling it, dragging it out by its throat and smashing it against the cinder block exterior of the house, but there’s no point. If she wants another, she’ll get it. My father will not stop her, and I can’t spend all my hours watching, hawkish and disappointed.

I want to go home, but there’s nowhere to go. My dog is dead, my mother’s a mess, and my father spends his days at his desk, typing one finger at a time, a slow click, click, click, like my boyfriends’ camera shutter. He’s not my boyfriend right now, but he was last week, and he will be next week. I hate him.

Back in Atlanta, everyone is relying on me—my professors who can’t recognize my face but use my work as an example of “good,” my boss who doesn’t know the price of food and vibrates like a chihuahua, my coworkers who are confident that I will fill all the cracks they leave, my friends who call me to pick them up and send me requests for gas money, my not-boyfriend that I hate who cries about everything and never says thank-you.

Most days I don’t eat. I don’t deserve to. I’ve stopped going for jogs around the neighborhood. I’ve run out of refills for my antidepressant and have not gone back to the doctor to get more. In a month, I will catch the flu, miss two weeks of school, and fail my first class. Later, I will get the grade expunged, but the failure will stick in the back of my mind like gum on the bottom of a desk and sometimes my fingers will catch on it and come away filthy.

The drafty old apartment I live in is not home, but at least it’s not here.

The ice burns my fingertips as I scoop it out of its plastic skin and into a quart sized Ziploc. I can’t feel myself sealing the bag, but I know that I have because I watched myself do it, and I wrap it up in a soft yellow towel trimmed by stylized, blue tulips. I carry the bundle to her bedroom, just off the kitchen, and kneel by her bedside because sitting on the mattress makes her nauseous.

“Hey, Mama,” I whisper. She does not open her eyes, just reaches out for me. I take her hand and pet it, feeling the way her thin skin moves over her bones, how her tendons flex when she curls her fingers around my palm. “I brought you some ice.”

She’d said she felt hot, and that was why she was lying naked on the bathroom tile when I got home from the grocery store. At least, that’s what I’d gathered from her mumblings as I wrapped her in the bathrobe I’d given her for her eighth Mother’s Day.

“I’m sorry,” she’d whimpered, leaning against me as I tried to shuffle her to her bedroom and pour her limp, cooked-noodle body into some pajamas. “I didn’t want you to see me like this.”

“It’s okay,” I’d said, meaning it, still breathless from the joy of discovering she was alive and mostly unharmed.

Her lips are stained wine red. It’s a good color for her, more complementary than any of her sample-size lipsticks and tinted balms.

As I arrange the ice on her forehead, pushing her long curls away from her face, I wonder if this should spark anger. But there is nothing bright inside me, just my crooked spine propping me up and all my organs writhing against each other and the efficient pistons of my muscles working in tandem to carry me back into the kitchen.

I open the freezer. The worm is still there. I grab the bottle by its neck and pull it out, disturbing a bag of Great Value frozen minced onions. Cradling it, I fall into a crouch, my bare heels flat on the linoleum. I press its cold body to my cheek and drown in the mezcal with the larva that will never become a moth.

———

“What’s your star sign?” she asks, fluttering her eyelashes.

We’re sitting in the same study room that she called my novel idea stupid in. I grimace, but to her it looks like a smile.

“Scorpio,” I say. I wonder if I should fuck her, just because I can.

The little voice in the back of my mind insists that it’s a bad idea, and I listen. Even though she calls my ideas stupid, jokes that I’m a loser, smacks my arm and says I’m awkward, I know that she likes me—has a crush, like a little girl, not a twenty-year-old woman. I know that she is everything she says I am, and that it would be cruel of me to take advantage of that, like fucking a little girl, not a twenty-year-old woman.

A year later, my therapist will ask if I even like having sex with women, and I will say, “I don’t mind it,” and she will reply, “That’s not the same.”

I wear my 4.0 openly, like an asshole. It wasn’t even hard to get—I can barely be proud of it. She’s already failed three classes and is only a sophomore to my senior. The ages don’t match up, though, and for a while I was silently, politely confused until she told me she was held back in third grade.

We met when she slid over to me in our anthropology class and shyly asked if I could help her with her Punnett squares. My first thought was not a kind one. This was third grade shit. Maybe that was why she’d been held back. But everyone learns differently, and I’d already finished, so I agreed. I explained the squares every which way from Sunday, only earning a soft frown.

“I guess you’re just one of those smart people who can’t explain stuff,” she’d said, giggling.

I gaped at her, my eyebrows hitting my hairline, wondering if she was being purposefully obtuse.

She invites me to a party, and I go because I don’t mind.

“I’m an extrovert,” she’d said in that study room, but at the party she all but hides behind me while I laugh and joke with her friends from high school, even though my heart is pounding and my hands are sweaty and I want to go home.

She wants the next person I kiss to be her. I know this because one of her friends tells me, her tone accusing, like I’ve somehow failed in a mission I didn’t know I had, broken a promise I didn’t know I’d made.

The next person I kiss is a boy with soft lips and a short beard who is a little too tall for my tastes.

I can feel the blade poised at my back, and even as it slips between my ribs I can only sigh, because I brought it on myself. It was naive to expect a little girl to take rejection in stride, especially rejection from a stupid, awkward loser.

“You’re an asshole,” she spits. “But I should have expected that from a Scorpio.”

She says it like it means something. Maybe it does. Perhaps I was born bad and should apologize. Instead, I take a deep breath and turn away, resisting the urge to lash out and sting.

———

A type of black magic practiced in Japan primarily by women, kodoku is a practice of trapping venomous insects such as scorpions or centipedes together in a jar and leaving them until one has killed all the others. The victor’s fluids are used to poison and curse an unsuspecting victim, sometimes to manipulate them and sometimes to kill.

As I read the words, I wonder how often a scorpion comes out on top. I wonder how it feels as it’s lifted out of the viscera of its slain foes and kept as a good luck charm, fed well to not enrage it. I wonder how much it wants to go home.

A gnat buzzes near my ear, and I snatch it out of the air, crushing it in my bare palm without hesitation.