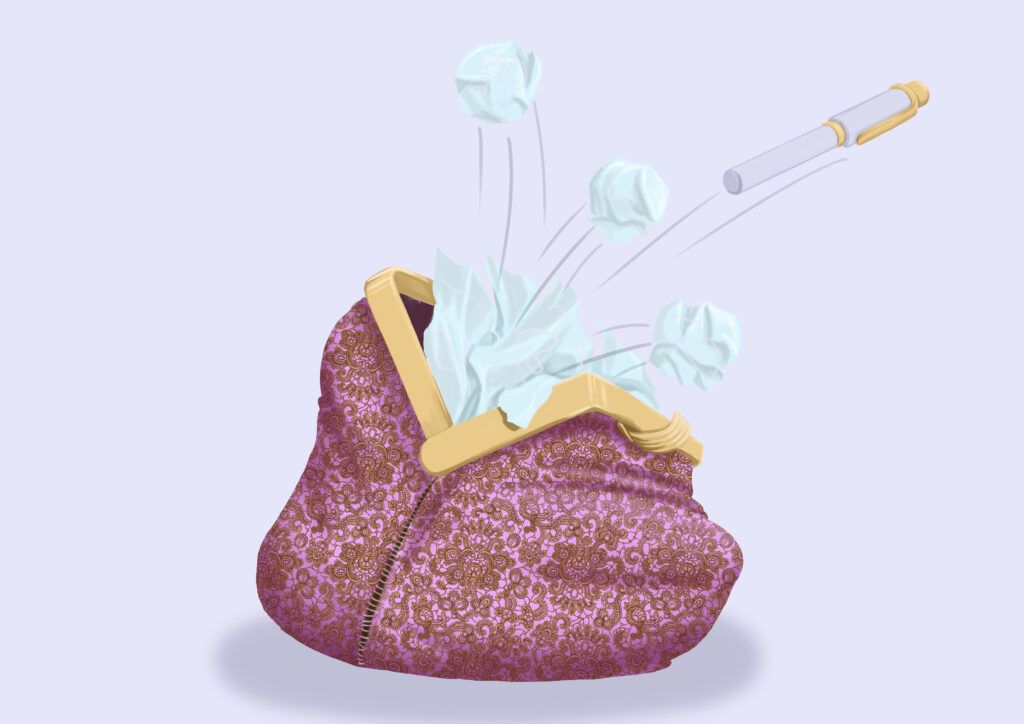

I knew it was my mother forging my signature because she signed it in lavender ink. She never failed to have anything useful in her purse the way other mothers did. No band-aids, no snacks, no wet wipes to clean the face of a child who’s just eaten ice cream. Instead, she had little notepads. Six or seven of them filled with ideas written out in illegible handwriting. Long were the nights when she would sit at the kitchen table under a dusty bulb and curse herself for her own sloppy penmanship. Alongside the notepads were lavender pens that held the same color as their exterior. My mother liked to be different, and even when she realized that her life would be spent conning other people out of their money, she couldn’t resist the urge to leave her mark. Like a bandit with a calling card.

Hers was lavender ink.

When I moved from San Diego to a small town on the east coast, I thought that might somehow convince my mother to stop impersonating me, but it achieved the opposite effect. I made the move when I was twenty-three. Prior to that, I had only been made aware of my mother signing my name to things like petitions and inside bestsellers at the local bookstore. I got a call one day from the manager at Compass Books asking me why my name was inside every copy of the latest Jackie Collins novel. This was back when you could look people up in a phone book, and I was the only Rutherford Coward in the entire city. My mother gave me a name that nobody else had, and then proceeded to use that name to get me in trouble. My name also seemed to be immune to her chicken scratch handwriting, because everyone who saw it could read it clear as day.

Why did she find the need to write my name in places it didn’t belong? I wish I could tell you. We stopped speaking shortly after my eleventh birthday when she dropped me off at my grandmother’s house to go run a few errands, and never returned. My grandmother had suspected ever since I’d been born that she might do something like that, so there was already a room made up for me in the basement and assurances that everything would be fine. The assurances weren’t needed, however, as I was relieved to be rid of my mother, or Jamie, as I began to refer to her. I know some people are capable of loving dysfunctional or incompetent parents, but that was never a skill I possessed. I spent the first ten years of my life feeling nothing but frustration that my mother couldn’t get her act together, and once she was gone, it was as though I finally felt myself being fit into a life I could live without friction. A placed in a spot on the shelf with exactly enough room to accommodate it and not an inch more.

The lavender signatures didn’t begin appearing until I was halfway through high school. That was when someone said they saw my name written on the inside of the stall in the men’s room at JCPenny. I thought this was meant to be some kind of lewd joke, but the person telling me was a friend, and he was only asking, because the handwriting didn’t look like mine. We had made it a habit of sharing notes in biology, and he always complimented me on the way I wrote my “w”s and “t”s.

“They’re not the same on the stall,” he said, “That’s how I knew someone else wrote it.”

“Was there anything attached to it,” I asked, “One of those ‘For a good time, call–?’”

“No,” he replied, seemingly a little unnerved that I would even suggest something like that, “Just your name. Nothing else.”

When my name started appearing elsewhere, other students were not so kind. One saw it written on the back page of a Bible in the church they attended, and they lectured me on blasphemy, even though I knew that wasn’t what blasphemy meant. I tended to take all this in stride, because I knew that as long as my mother was out there writing my name down it meant she hadn’t forgotten me, which was touching, but would normally have indicated that she’d be returning at some point. That was enough to make me go running to my grandmother insisting that I’d never go back to Jamie, only to have her point out that my mother wouldn’t drum up all this chaos just to pick me up one day and help me sort it out.

“Does that mean that she’s mad at me,” I asked, “If she’s putting my name down in places where it shouldn’t be?”

“I don’t think so,” my grandmother said, in the middle of stuffing a chicken for dinner, “She doesn’t think about anything she does, Rutherford. She just does things until someone tells her not to. That’s the problem with her using someone else’s name. Nobody’s ever going to tell her to stop, because nobody but you knows she’s doing it.”

She shoved the chicken in the oven and I made a mental note to turn down the heat by about five degrees. My grandmother was a saint and a sage, but she couldn’t cook to save her life, and I often had to rescue her dishes without her noticing.

“If you like,” she said, “We could try and find your mother. I could hire a private detective like on Moonlighting.”

“No,” I said, “On Moonlighting, there’s always some kind of twist, and in this case, the twist might be that I wind up back with my mother in some kind of tender-hearted scene towards the end, but that’s not really what’ll happen. What’ll happen is she’ll take me away from here, and I’ll be stuck living in another rundown apartment with her while she works as a tutor pretending she can speak French and Italian.”

“My god,” grandmother said, cracking open her third beer of the night, “Every story you tell me about her is worse than the last. How on earth did she end up like that?”

I weathered the next few years hearing stories about my name being written on napkins at Applebee’s and in chalk on the ground by the playground where that kid died once from an asthma attack. Soon, everyone knew that it was my mother forging my name, and not me on some kind of wild branding campaign. I’m sure a few people doubted my story. Why would a mother abandon her child only to then put his name everywhere she went? I wanted to know that as well. I would have settled for someone actually catching my mother in the act. Despite the prolific nature of her actions, nobody had ever seen her writing down my name. The only proof I had that it was her was the lavender ink and wide valleys she gave my “w.”

When the time came to move, my grandmother packed me two ham sandwiches and a few beers. “Don’t drink them while you’re driving,” she said, “Save them for the end of the night.” I wouldn’t be twenty-one for a few years, but Grandma was Irish, and as far she was concerned, if I could drink in Dublin, I could drink anywhere. Luckily, the fear I had of a latent addictive personality kept me away from drugs, alcohol, gambling, and certain soap operas. I gave the beers to a trucker outside of Phoenix, and I ate the ham sandwiches at a rest stop in Fort Worth. My path to the small Rhode Island town I’d wind up in was a wiggly one on purpose. I had a vision of my mother tracking me. Trying to follow me across the country while scrawling my name on menus in diners and on the front pages of local newspapers above the minutes of a school board meeting.

Upon arriving at the converted church where my new studio apartment would be, I felt as though I had made it off a collapsing bridge just before it hit the water. I had no furniture, no job, and only a cooler filled with ham sandwich crumbs to my name, but I was finally free. No more being haunted by my own moniker. I remember that first night sitting by an open window at an angle that almost allowed me to see the nearby ocean. I said a silent prayer of thanks to St. Francis de Sales, the patron saint of handwriting, for finally allowing me to be the only one who would write my own name. A fishy breeze came in through the window, and I took in too much of it and began to cough.

That should have been a sign that all was not New England liberation.

My mother located me. The how is, like everything else, a mystery. I only knew she had found me when I saw my name in lavender graffiti on the side of an empty building near the place where I had begun getting my morning cold brew. When I passed by the community message board at the local library, my name was written on the bottom of every flyer. I realized I would have to use a pseudonym or risk being associated with these signatures around town. People were already asking just exactly who Rutherford Coward was, and why did he feel the need to make his name known wherever there was a blank space–and why the funny-colored ink?

After working for several years at the local bank, I was made branch manager, and I was able to put a down payment on a house. While signing the appropriate documents, the real estate agent remarked that someone in her neighborhood had begun leaving scrap paper in all the mailboxes with a single name on it. An unusual name too. I smiled and said, “How odd,” but inside my stomach was frothing. When would this end? Where was my mother even staying? This has been going on for so long that I assumed she had to have gotten a place somewhere in town, but I had yet to run into her. Just as it was in San Diego, nobody could find the person using the lavender ink to write the funny name. Unlike back home, I wasn’t there to defend the name they were all seeing, and so Rutherford Coward became the enemy of the town. It was impossible to walk into a pub or pass by an outdoor table at a cafe without hearing someone fantasize about what they would do to this Rutherford character if they ever ran into him.

Eventually, no matter how upsetting, harassment will melt into the air the same way carbon does. Your body is aware of it, but your mind becomes occupied with other things. The daily traumas rather than the wider ones. It’s not that the names stopped appearing or that the chatter around them discontinued. It was that I divorced myself from the matter entirely. Soon, it was as though I really didn’t know who Rutherford Coward was, and I could be as annoyed as the next person seeing the name written down in a book of songs on karaoke night or on the container of a latte waiting to be picked up.

I knew my mother was gone the day I woke up with my name written on my arm. I looked down, and there it was in all its lavender glory. There was no doubt that she’d been inside while I was asleep. She must have assumed that I was still a deep sleeper just as I had been when I was a child. Every door in my house was open and every window. It was the middle of February, and the cold woke me before the alarm did. As I walked through the house to make sure she wasn’t there, I began to feel a sense of closure crawl up my side. Something about the experience felt satisfying. Yes, I had been violated, but it felt as though the violation was the final price I had to pay to be rid of her. She had never marked me in any way until now. The writing itself didn’t have its usual cleanliness either. The “h” looked sloppy, and both “o”s were left open rather than closed at the top. She might have been afraid that I would wake up as she was inking me, but I didn’t think that was it.

There were spots on my arm. Little black dots. Mascara teardrops perhaps? I’m no writer, or I would be tempted to guess what it all meant. Instead, I had to choose the ending that gave me peace. That’s why I say to you, Yes, she was finished. With what, I don’t know. I’ll remember her, but I’ll never love her. I’ll tell stories about her, but she’ll never be the hero. She’ll always be my mother, but I’ll call her Jamie and nothing else.

There is one small fantasy I’ve allowed myself.

One day, when I receive a call from some coroner somewhere letting me know she’s passed on with my name and address on her person, I’ll pay for a simple funeral and a plot of land. I’ll bury her. I’ll watch as the coffin goes down. No one will be with me. The cemetery will be far from where I live so that I’ll never be able to visit. I’ll get a room at a nearby hotel for a couple of days until the dirt has settled and the tombstone has been erected. Before I head to the airport, I’ll go to her grave, and, removing the lavender pen from my pocket, I’ll write a name I haven’t used in years on the cold, cold cement.

I don’t know if you can mark a gravestone with ink, but in my fantasy it shows up brilliantly. Bright and bold.

Impossible to remove.