Jimmy feels guilty as a Catholic school boy playing hooky – which he never did, not even to watch Popeye the sailor and his corncob pipe on TV – taking a day off from the cafe. It’s foggy and cold. Eye on the prize, he thinks, squinting like the bald cartoon character. Jimmy and X have her mom’s Victorian flat and begin with second-cracked coffee beans from Yemen.

“Crack?” she giggles in a yellow terry robe. She’s curled up on the Chesterfield in front of the retrofitted 1950s TV wood console, watching a SpongeBob Square Pants DVD he burned for her. “Wait, the coffee beans the Dutch settlers thought were cocoa before roasting the shit out of them?”

He loves that she cusses like a red-neck sailor, unlike Popeye. “Ya, mon,” Jimmy Rastafarians white as Popeye. “The second crack is softer-sounding than a popcorn pop. Then the oils migrate dark chocolate and red-wine qualities from inside to outside the bean.” Then he adds, “Like the butter is already inside the corn kernel. Anyway, right up your alley.”

“Up my what, man?” she funs with cunning, beet-colored hair fraying from ropy plaits. Her robe opens, there are tantalizing flashes of milky skin and a thicket of carnal love.

White dress shirt and bell-bottom cords, even dressed as a Catholic school boy X says, he ladles dark-roasted ground peaberries with boiling water from a pot into a papered ceramic cone atop a steel thermos. They drink crude-oil thick coffee swirled with heavy cream as she belly-laughs at the boob tube. It’s an infectious burst, endearing, the kind turning heads at dinner parties or the theater.

“What?” she says. “I can like cartoons. Even Popeye.”

“I know,” he says. “It’s why I brought the DVD.”

“Right,” she says with a voluptuous smile. “Thank you. By the way, the coffee is amazing.”

She’s half French with a slight accent, half his age, and fully Ivy-league educated in art history. She’s a waitress, a wine connoisseur, and an amateur aesthete with the sculpted nude back of caryatid. The gracile legs of a runway model, she reeks Greek art, holding up the ideal of beauty. He’s obsessed with even her thirty-two polished teeth, one shy of a messianic smile.

“What’s that mean?” she asked once.

“Jesus was 33.”

“You are so weird,” she said.

While she binges on cartoons, he prepares the meal. The house is warmed with aromatics, herbs, and alliaceous smells.

“Is that epazote I smell?” she yells.

“No, what episode are you on?”

She doesn’t answer, there are only kernel pops of explosive laughter.

The weather clears and the foghorns stop, obeying his wishes. She doesn’t and makes him wait. Eventually, she dresses and brushes out her tinctured hair – one hundred strokes.

They picnic on the balcony. Spring mix, kale, and spinach for the Popeye effect, he jokes. In the cartoons, Popeye swallows a can of cooked spinach in times of peril like a fight with nemesis Bluto, giving him instant heroic strength and knock-out victory. But fresh is better, X says. Thus the raw baby greens with garlic croutons and balsamic vinaigrette applied at the last moment so nothing goes soggy or limp – a Kamasutra cooking of sorts. Also, there’s seasoned slow-roasted chicken. Compound butter leaks under crisped skin, exposing bone and marrow. The cavity bulges with a Meyer lemon and Rosemary. On the side, wedges of brie, skins flensed like bread crusts. For dessert, poached pear in left-over coffee with rum and white chocolate shavings.

A half bottle of wine in, Jimmy wants to probe the question, the possibility at least. But as X

sips from a tastevin, a relic from her enology training in Bordeaux, she points and says, “Look.”

What now? he thinks, squinting.

Across the street, a muscled vicenarian in blue jeans and a torn V-neck T-shirt unloads a love seat from a moving truck in front of a dilapidated A-frame house. The wall of the cargo box says EARL’S MOVING COMPANY in cursive black letters. Cars speed by, heading to the sea. The sun glints off wiper-streaked windshields, splashing the black-tarred street. In the distance, the Golden Gate cants as though on Conch Street. It’s where SpongeBob, a square yellow animal sponge in square pants with skinny legs, lives on the ocean floor in a pineapple. A shipwreck resides nearby, the ballast broken over. A very boyish cartoon character, he’s a fry cook at the Krusty Krab with buck teeth, blues eyes, and freckles. He gets into trouble or funny situations. Jimmy’s gathered this much.

“OMG,” X says, tugging on Jimmy. “Earl is gonna hoist the settee into the second-story window. I just know it.” She picks at the chicken carcass and tosses the wishbone over the rail.

“How? Why doesn’t he use the stairs?” Jimmy sees them through the open front door and

considers the unbroken wishbone, knowing what he would have wished for as she Wet-Naps her nubile fingers.

“Earl’s a weirdo freak. Know what I mean?”

“Ya, mon.” He thinks of tricenarian Coach Earl from Little League – when that weird freak thing happened. More than three times.

“My mom saw this shit yesterday. She told me and her boyfriend all about it.”

“She should have a camera for those reality TV shows. TMZ. BFD.” Jimmy is glad Earl didn’t

have a camera decades ago, though he sees the rerun daily.

“BFD?” she says.

“Big Fucking Deal.”

“That’s not a reality show.” She laughs and grabs his thigh. “That’s why I go out with you –

BFD. Sometimes you are so funny.”

“Is this one of them?”

“No.” She grins sideways.

Then she says, “My mom’s old scuzzy boyfriend has a big fucking camera, but he’s a Chester.

Did I tell you he came into my bedroom?”

He knows that word from a distant time. A pervert in disguise is what he thinks she means. Chester the molester. But it’s the word came that sticks in his thoughts. He says, “Were you clothed?”

“Yes, but he walks in like it’s one of his restaurants. It’s bad enough he lives next door.” Then

she says, “I don’t think Mom needs me around anymore since Dad died. I really should get my own

place.”

He wishes she said we and our. “So, what did the Chester want?”

“He said he was looking for my next pairing.”

“Pair of what?” he jokes.

“Wine pairing.”

She is annoyed, plucked eyebrows scrunched, and brushes her elbow. Her plum blouse opens, flashing lambent breasts – the sommelier moneymakers. He wonders where she keeps the corkscrew and church key during service. She brushes faster as though depluming a chicken.

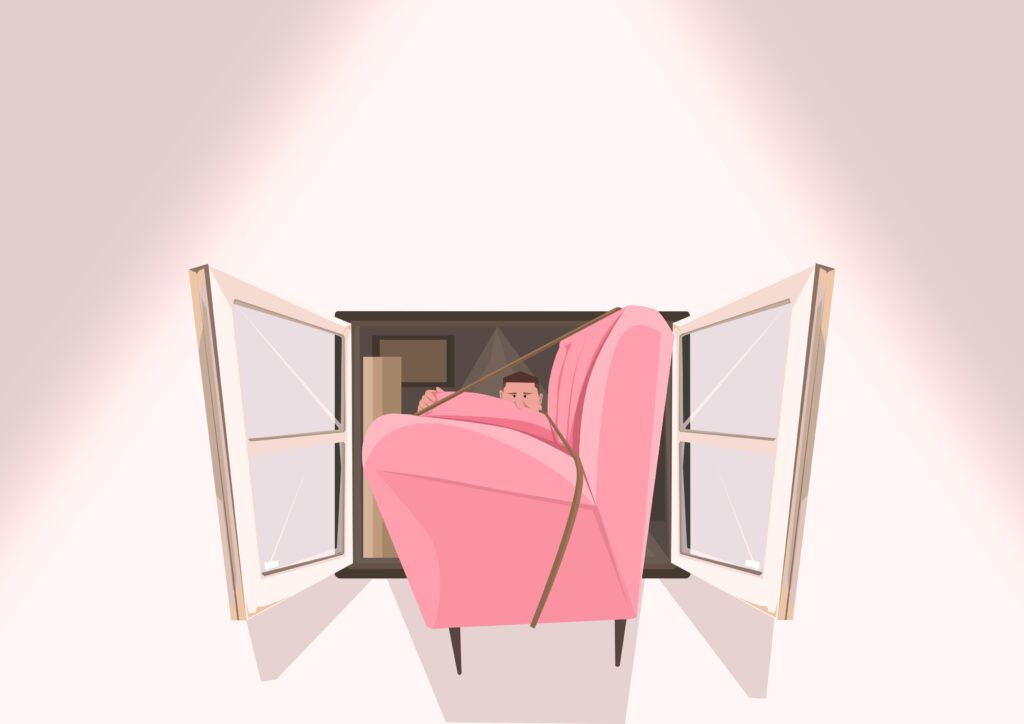

Across the street, the man in a gray t-shirt with sweat rings under his arms disappears into the A-frame. He appears in the upstairs window, open like a barn door, its frame peeling. He looks right, he looks left. Victorians on both sides gleam chrome soffits and soft-blue Doric columns with fresh paint. Alarm stickers footnote new glossy windows. Blackberry privets bloom with trimmed boxwood below, earthed in loamy soil. The man throws out a braided rope thick as a hawser, one end anchored inside. The rope wriggles, then stills. Jimmy imagines ships from Popeye cartoons scaling the facade.

The man disappears and comes out to the street. As cars roar by, he ropes both ends of the

love seat, then down the center, trussing like a capon. He draws it taught. Then he lifts the love seat,

leaking cotton, onto an oil-drum coffee table. He disappears into the A-frame and appears in the

upstairs window, looking around, rubbing his hands together.

Jimmy says, “He should have gloves.”

She doesn’t say anything.

He knows she’s thinks he means rubbers, she likes it raw.

“I should help him,” he says.

“No, don’t,” she says. “Only pussies need help.”

Jimmy looks at her.

She says, “Did you see his big-ass football Popeye forearms?”

He notices his own – thin and undeveloped. Like your career in coffee, she’s said, a dig

like Earl’s short fingers in his behind. He wonders if the cafe is short-handed and needs help.

“He doesn’t need help,” she says. “And I bet he doesn’t smell like baby powder, either.”

She took a loofah to his armpits in the shower earlier, scrubbing harder than on a tastevin tainted by a bad bottle of wine. Jimmy is vintage and yet amiss like that, she’s said, harsher than a celebrity roast. Boyishly handsome with piercing blue eyes but balding as a gourd, grape, or Popeye. And breath bad as a sailor’s wind-blown ass.

He drinks with wine already in his mouth. He looks at the bottle, the label says Verdot.

Imported from France. Low acid and sulfites. There’s enough for another glass.

Across the street, the man masts the love seat up to the A-frame window. It rests on the glommy sill and sticks out like a giant tongue in a painting with too small a frame.

“Is that Surreal?” Jimmy says.

“Hell yes,” she says. “FR.”

“FR?” French Realism? he wonders.

“For real,” she slangs. “It’s like a fuck you and a dare at the same time.”

The man yanks, pulls and tugs, the whites bugging from his eye sockets. The love seat won’t budge. The man rubs his hands together, then disappears and comes back out to the street. He surveys the love seat in the window. He calculates from different angles. He stands to the left, he stands to the

right. He raises a thumb, guides it eye-level.

“Earl’s a limner,” she says.

“What’s that mean?” Jimmy says.

“A painter of portraits or miniatures. Or in this case, of possibilities.”

And I’m a weirdo, Jimmy thinks.

Then, with cartoon aplomb, the man climbs on the oil-drum coffee table for attitude. He scratches his full head of hair, eyes vulpine as a pedophile’s. Jimmy looks the other way to lessen the oncoming memory of gut-wrenching guilt – like the dip of a roller coaster, the one Earl took him on after the motel. Tightening his stomach does not help.

On the street, a sports car slows up, honks, and the man motions.

“Did Earl flip off that motorist?” X says.

Motorist, he thinks. Who says that anymore? “Guess so. BFF.”

“Freak.” She laughs. Then she says, “Wait, BFF? Doesn’t fit.”

“Big fucking finger.”

She howls again. “Oh! Bet that would fit.” She wiggles in her rattan seat.

The man huffs into the house and appears in the window. He pushes the love seat out. It tilts. He maneuvers and loosens the reign. But it’s hooked. Then something – a piece of ledge – chips and falls

to the ground. The love seat drops, then catches, dangling like a hanged outlaw.

“He’s gonna lose it,” Jimmy says.

“Na, he’s got it.”

And like that, the man wraps the rope around his hands and yanks the love seat through the window.

“Voila!” the girl belts out. “Done.”

“Jesus,” Jimmy says. Hoping that’s the end of it, he finishes the Verdot.

———-

“Think anybody would look or notice?” she says minutes later.

“What?”

From the balcony, she looks across the empty street, then up and down it. She kneels in front of Jimmy, a genuflect of will, he hopes.

As he looks at distant windows for faces looking back, she unfastens his belt, then his pants.

She draws them down, then his boxers, pushes up his shirt, and his belly lumpens out.

“You should work out with me at the gym. Running a coffee store isn’t enough.”

I’ll let you work out alone, he thinks, as she lowers her small mouth on him. Her luxurious hair

bounces on his lap like a mitter curtain at a car wash. Always squinting in the abundant light, Jimmy closes his eyes. He sees soap suds on the hood, hot spray on the windshield, brushes spin on wheels, all

washed away as the sun seeps through. Opening his eyes, he sees stars and watches as she uses her

hand too.

After, she wipes her mouth. “Think he noticed?”

Jimmy nods as the vulpine man in the window of the A-frame looks at them like Earl at Jimmy

in the dugout and motel shower.

———-

“Let’s get married,” Jimmy says and fastens his belt.

She gulps from the tastevin, sans spittoon, and swallows. She says, “We should do our

dishes. Mom will freak if we leave them.”

Jimmy grabs the cutting board, pear remains and salad bowl in which some dressing has pooled at the nadir. As a boy after dinner, when no one was looking, especially his mother because she said it was uncouth and something you didn’t do or talk about, he’d lick the salty rim clean and drink the last of the yummy, vinegary Seven Seas and soaked herbs. He’d even mop his fingers like bread to wipe it up. He muses that’s what Popeye or Sponge Bob might do. But there’s no time; X grabs the plates, glasses and empty bottle. Jimmy looks down the balcony for the wishbone before going inside.

———

Next evening, he pan-sears salmon fillets scored with dill in olive oil. He smirks at Olive Oyl – the name of Popeye’s girlfriend, thin as string beans sauteing next to resting roasted sweet potatoes. I yam what I yam, he recites – part of Popeye’s musical refrain. For dessert, shaved Parmesan and chili-honey. A candle illuminates the picot table cloth – the wax smell of church, solemn as a refectory before he left the seminary to get married. He looks out, thankful not to see the man. The A-frame is shuttered, draped by beige bath towels, shabby as motel curtains – there is always something to recall Earl. On the street, the dirty moving truck sits locked, metal ramp trundled. Cars headlight by. Dusk has set in, a flaxen hem on the horizon.

“All moved in?”

“I guess. Mom’s boyfriend offered to help and the guy said no and disappeared. Dumb fuck.”

“The man or your mom’s boyfriend?”

“Who do you think?”

“Where are they, your mom and boyfriend?”

“Where else?”

“Just asking.”

“Working at the restaurant.”

He sees them toiling like Sponge Bob at a high-end restaurant. Fountains of sweat, financially under water. Then, finishing the Franc, Jimmy asks, “Are you sure you don’t want to get married? It’s been two years.”

“Some people date for longer.”

“Are we some people?”

“You drink too much.”

Don’t bring up AA; it’s for quitters, he’ll joke, recalling her attending an Al-Anon

meeting. She barhopped til close and dialed for an assignation. Jimmy, hungover, was waking for work.

“Maybe we should see a therapist,” he says.

She glowers like his mom when he admitted as a child he was bleeding down there.

“You were already married once,” X says, clears the table in a lemon pullover, sleeves

hiked to the elbow. Her naked wrists and fingers agile a crumber with aplomb, wipes the laminated place-mats clean. At the sink, he dries while she washes hammered copper pots and pans. Then she stacks the dishwasher rack from the rear, never rearranging. He polishes the stove. The smell of

bacon and fish fug linger. She sweeps the kitchen floor. Twice. “How did you get so much salt every-

where? Was Judas here?”

“Judas?” he says.

“Da Vinci’s Last Supper. Judas knocked over the salt cellar.”

“You studied wine and art history; I studied theology. I just threw some salt over my shoulder

for good luck.”

“Trying to get lucky?” Her smile buckles his knees.

“Always.”

“Are you staying then?” she says, putting the broom away.

“Do you want me too?”

“If you want.”

———-

Later in bed, she says, “I can smell your deodorant. Can’t you wear anything that doesn’t smell like baby powder?”

“Maybe I should leave.” He fumbles his square pants, the belt buckles the wood floor. He turns the light on, squints, and reaches for socks and shoes.

“No, don’t. Just don’t wear it anymore.”

“I told you why already.” He puts his pants on by the door.

“Come on,” she says. “It’s only deodorant.” She covers her breasts with one arm, the other at

her side. The percale sheet and duvet are heaped at the foot of the bed. On the other end, like a cartoon

character, a pink finger-sized vibrator peaks out from under the pillow. Patrick, he thinks, SpongeBob’s

best friend.

X says, “Take your pants off, come here.” She pats the mattress twice.

He closes the door.

“Could you lock it? But keep the light on.”

They face the closet mirror. He ruts from behind on her knees while she uses the vibrator with one hand, bracing with the other. He traces narrow spine and emaciated ribs to the declivity of her waist. He grabs on to the swell of her ass.

“Be an animal, be a freak,” she says. “I dare you. No one is looking. Lick it first.”

He hesitates.

“It’s clean.”

His tongue glances her sphincter. X quivers, already agape and unguent as if lubed. He straightens, she drops the vibrator, then takes hold of him. She navigates, backing in slowly. He plunges through.

“Oh, my God,” X says. “You’re in.” Then, “Look,” she half grunts and whispers. “Jimmy,

lo – ok.”

She reapplies the vibrator and he looks at the mirror, a juxtaposition of what Earl did. Now Jimmy is doing it. He feels guilty as a hypocrite. It distracts him, this rear-ending pedication-style glove-less act. And the taunting language he can’t unhear. Lick it. Also, that he can’t talk to X about it distracts him. Being watched distracts him. The thought there might be blood distracts him. The jackhammer hum of the vibrator distracts him.

She drops the vibrator, arms giving way like a crumbling bridge. Pinioned, she jerks, she spasms. Eventually, she comes, prolonged and very loud. She breathes into the pillow.

Wait, he thinks, did she call out Earl?

Jimmy tries to withdraw. But she says, “No, don’t stop.”

Then she says, “You’re just pushing rope.”

He rolls off limp, smeared with fecal scrim.

They lie quietly.

“Here,” she says, using her hand, getting him hard again, then her wet mouth.

Wait, he wants to say, wanting to wash.

But her hair bangs all over, she devours him like a python and goes back to her hand. He turns flaccid.

“No,” she bemoans softly.

What he wishes he’d said to Earl.

“Fine,” she says. She turns out the light, turns her back, and they go to sleep.

———-

Next night at dinner, X says, “My mom’s boyfriend videotaped Earl.”

Jimmy is cautious of her cartoon and reality TV raconteur; she’s full of wine sans tastevin. She drinking from a glass and opens another bottle. Jimmy won’t say no to another drink. “When?” he says.

“Today.” She has him smell the cork.

“Blood and musk.”

“I’m using that one.”

“So Earl?”

“I’m getting to that. How’s the wine taste?”

“Astringent tannins, thick blood, and grape musk.”

Sipping, she says, “Fare enough.” She puts the glass down, almost knocks it over. She says, “He was back at it. Mom’s boyfriend saw him walking his smelly dog. He hurried back to the house and got his circa 1940’s camera and filmed from the balcony without the guy seeing him.” She tops off Jimmy’s glass, continues, “Oh, it’s so funny. It was a big fucking deal. The guy was trying to hoist a huge bed through the window. You really should see the video, it’s so funny.”

“As SpongeBob?”

“Funnier,” she says seriously.

“What kind of bed? A queen, a king?”

“Some big, thick-ass piece of floppy mattress shit. Anyway, he dropped the bed three times! The guy was so long at it, my mom’s boyfriend almost ran out of film or memory or whatever!” She tosses her crumpled napkin, covering the salt shaker.

Jimmy drinks, feels mute.

X’s drunk smile reappears, unveiling grand, piano-like ivories. “So, on the third time,” she says, “the guy fell like your messianic Jesus!” Incisors nearly puncture her bottom lip. “Can you believe it? The king of the Jews fell on a king-size bed! Or maybe.” she says elusively in French, “Comment dit-on?”

“Come on, what did you say?”

“J’ai compris.” She translates, “I got it. Popeye after a can of spinach, punching Bluto aka Brutus for making a pass and grab at Olive Oyl. Knocked his shit out the window. Anyway, Earl almost rolled like a square through the thicket of bushes into traffic.”

She laughs, the sounds no longer infectious. Her brushed, lavish hair bounces. So do her magnificent breasts.

Jimmy pictures the man falling, flailing, almost wish-boned by a car, blood nearly shed. It’s too brutal even for Coach Earl. Jimmy finishes the roasted lamb and slow-cooked ratatouille, the cubed flash-fried eggplant still firm. Then he gulps the appellation Bordeaux – the last drop isn’t enough. He sucks the rim of the glass. Then he wipes his mouth with the linen napkin and folds it back on his lap, eyes no longer on the prize. He doesn’t care about asking anymore, about anything. His armpits burn

from a new alcohol-based deodorant, peeling like the chancroid sores Earl gave him as a boy.

Jimmy feels no guilt passing on coffee, dessert, and not staying the night.

“Look,” he says.