I learned to say “McCutcheons” before I learned to say “ornery,” “disorderly,” “drunkard,” or “mental,” and certainly before I learned to say “schizophrenic.” These and similar words were all used as synonyms for “McCutcheons.” My parents made their last move when I had just finished first grade. I was blind to what circumstances might have led to our own move. But my eyes were wide open to the new neighborhood we found ourselves in and the characters who populated it. I was wide-eyed as I rode with my parents and my sister to meet the moving van at the new house, the two of us kids hanging over the back of the front seat. I could see the van ahead on the left when my attention was drawn as if by force to a house on the right, three doors before our new home. A white vehicle like an ambulance, but larger, sat in the driveway. Two men in white coats were struggling with a wild-eyed yellow-haired woman in a stained apron and a flowery dress. One man held her from behind around the waist while the other man shielded his face with one forearm and waded into a buzzsaw of flailing arms and legs. For a split-second as we passed, I heard a voice shrieking, “Merciful—.” In the door stood a man in a white sleeveless undershirt and grey dress pants who seemed strangely placid, hands in his pockets, while three children peered out of the door from behind him with expressions of shock and dismay. My parents acted as if they had seen nothing, though I could hear them clearly discussing the situation later that evening.

The news took some time to filter through the grapevine to the new people on the block, but before the end of the week, we had the full scoop. Actually, my parents never repeated gossip when they thought my sister and I could hear, but they grossly underestimated our aural acuity. This was not Mrs. McCutcheon’s first visit to the state mental hospital two towns over. As a backdrop to this most recent event, the grapevine wondered whether Mr. McCutcheon would succumb to another bout of the bottle and potentially lose another in a long string of jobs. And whenever the story was recounted, the last point to be made was that Ronnie was old enough now that he could join the Navy and get out of that nuthouse. Ronnie was not at home when his mother was hauled away – the preferred term – in the most recent incident – also the preferred term. He was at the high school where he was taking summer classes to officially graduate. He had been able to walk with the rest of his class – a fact I expected should be self-evident if you looked at him – but apparently, that was not something that could be safely assumed. The grapevine loved to mention that Ronnie knew getting his diploma would mean so much to his mother, even though she was probably not aware of the fact that he was graduating. I remember thinking this a simple oversight or poor communication on Ronnie’s part; a son should let his mother know when he’s doing something as important as graduating.

What the grapevine left out, but I soon filled in, was that the three children standing in the doorway had been Robert, Timothy, and Belinda. Robert, called Bobby, was six months older than me but in my grade. Timothy, generally referred to as Tim, was six months behind me and fell into the grade behind me. And Belinda or Bea was eighteen months ahead of me. All their birthdays, including Ronnie’s, fell in the same week in October. There was also an older sister who was in tenth grade whom I didn’t see for some time. I soon learned that the McCutcheon kids had to do their own laundry if they wanted to wear clean clothes. The girls’ clothes tended to be clean but shabby. The boys’ clothes, with dirty smudges and stretched collars, always gave the impression that they had just come from a dirt-ring wrestling match. I saw this as simple fact, neither good nor bad.

Having more than three kids usually meant Catholic, and not having one every two years marked them as Catholics having issues – not what the grapevine referred to as “good Catholics.” Next to the McCutcheons were the Mahieus, another Catholic family. The label of “good Catholic” was not applied to them, since they had only three children and that apparently by choice. As an Anglican, I often wondered what kind of training went on in the Catholic church and the Sunday school they suspiciously called catechism. All the Catholic kids at school seemed to know what was required to be a “good Catholic.” While I sat in Sunday school learning about Noah’s Ark in the Anglican church, I imagined the Catholic catechism teachers laying out family planning lessons on the blackboard – the proper schedule for births, the proper order of sacraments. Of course, in first grade, I didn’t realize that we Anglicans were the ones actually doing the family planning.

Across from the Mahieus was a small matchbox of a house where the Wrights lived. We would meet them later that week at the Anglican church. The Wrights were a marvel. They had seven kids and two bedrooms – that meant one bedroom for the seven kids and the other bedroom for Mr. and Mrs. Wright. “Obviously,” said my father, “Otherwise there wouldn’t be seven kids. Do you think they know what’s causing this?” Dennis Wright was a year older than me. If the Mahieus had seven kids, the grapevine would apply the label “good Catholics” but for the Wrights, the mention of having seven kids always seemed to produce squinting, wrinkled noses, looks of abject puzzlement. The mention often ended with, “Yeah, they’re Anglican,” as if that changed the equation, or flipped the equation into a riddle.

Kids being kids, it was no time before I knew all the elementary-school-aged kids on the street. And despite every fact in the equation arguing against it, Bobby McCutcheon soon became my best friend. And his sister Bea soon became my blessed obsession. Through the particular lens of my youth, Bea had the benefit of being slightly more mature while still having the accessibility that comes from being a neighbor and a friend’s sister. I esteemed her in those years above all womankind in my orbit – smarter, funnier, more graceful, and more skilled at the kickball arts. But to the kids at school, Bea was best known for being the beneficiary of her older sister’s hand-me-downs. In addition to the stigma of being several years out of fashion and having the wrong color palette, she also struggled with mismatched buttons and minor accommodations that school-aged girls are genetically unable to overlook. She probably suffered the most of all the McCutcheon kids from being a McCutcheon. I ascribed to her the infinite grace that must be necessary to endure the schoolgirl calumny of being out of fashion. In reality, I probably only noticed such things because my mother, seeing us playing in our yard, would pull Bea aside. She would talk in hushed tones with her and then pull out her sewing kit and there on the front step swap out a button or re-sew one with the right color thread or sew up a hem that was hanging. Such was her alacrity with needle and thread that Bea rarely missed a turn or held up a game.

For a few years, Bobby, Bea, and I made up a regular unit, whether it was kickball, hide-and-seek, or water balloon fights. We routinely took on the alliance of the older kids and the slightly younger kids, and we regularly triumphed. These were summers of water hoses, flavor ice, and bicycles. I would grab Bea’s hand first to form a line for Red Rover. At the same time, I took special delight at knocking her out of red-light-green-light or simon says.

My fourth-grade year, we began fishing at the pond down the street. Bea carried Ronnie’s pocketknife which she lifted from his underwear drawer. She showed me how to hold a perch or a steelhead catfish, so it didn’t spike me with their spiney fins, and she taught me to clean a fish in three quick motions: “In where he does his business and up to his chin. Then off with his head and off with his tail.” I once overheard my father saying that if I kept hanging around with those McCutcheons I was liable to be learning things sooner than I should. I imagined he meant things like the fine art of cleaning a fish.

In spring of my fifth-grade year, I looked forward to the return of fishing season with particular eagerness, and when the weather finally cooperated, we made plans to meet at the McCutcheons and then continue down the street to the pond. I left the house at five A.M. and hurried down to their house on my bike, steering with one hand and holding my fishing rod and tackle box with the other. Bobby met me at the door and let me in. We eagerly jabbered about our choices in supplies – a new bag of hooks, these really great rubber worms, a coffee can of nightcrawlers dug up the night before, a canteen of water. “Where’s Bea?” Bobby shook his head. She was nowhere to be seen.

I would never again eat a flavor ice perched next to her on a front step watching her lips and tongue turn purple or yellow. Bea had moved on. She was no longer one of us. She had metamorphosed into something else, something distinct. She had become a different kind of creature. And the next time I saw her, it was clear she had completed whatever transformation it was that had removed her from my orbit. For the next few years, I would still watch her from afar and think fondly of her, exchange waves, share a quick hello.

It was around this same time that Mr. McCutcheon started to show cracks. Mrs. McCutcheon had been good for the most part since we had arrived in the neighborhood those few years earlier. There had only been one awkward moment when Bobby had balked at whatever plan I had laid out. I pushed until he finally said, “My Mom’s not good right now.” There was no more said about that. And my understanding of the situation never went beyond “she’s good” or “she’s not good.” There was no discussion of what “not good” meant. When Mrs. M was not good, the McCutcheon kids either showed up at strange hours or disappeared altogether. But she seemed to be stable for the most part and regularly present in the neighborhood, as small kids would keenly observe. But now Mr. McCutcheon was showing cracks. He went from not being around during the day, like most parents, to suddenly appearing in their living room or stumbling out of their bathroom. There was never any discussion of what or why, but Mr. McCutcheon would usually attend Bobby’s Little League games but stay in his truck parked beyond the center field fence. Ronnie was in the Airforce (not the Navy). And the older McCutcheon girl had graduated high-school and then some secretarial school and moved out on her own.

The next few years, Bobby and I were thick as thieves. We built forts in the woods, traded baseball cards, explored every dirt road within a ten-mile radius. We cleared snowy driveways to play basketball in December and January, and then we would have to rotate basketballs from inside to outside every fifteen minutes, as each ball would grow cold it would lose its bounce while our fingers would lose their feeling. We would step inside, switch balls and blow on our hands, and then repeat the cycle. We cleared snow-covered ponds which then magically attracted grade-school skaters and hockey players. We laid out and mowed diamonds for wiffle ball with borrowed push mowers, and scads of neighborhood kids materialized like twilight lightning bugs. We hit baseballs in the backyard, losing balls in the woods, in the neighbor’s yard, and occasionally in windows. Throughout those years, we were heroes, demi-gods, wilderness adventurers.

I noticed that my mother began asking Bobby if he wanted to stay for a snack or lunch or dinner. We soon became interchangeable in both of our families’ houses, Bobby able to slot into our house at meals, television viewing, family discussions, and me slotting as easily into his. But my mother seemed to make sure that Bobby left with a full belly or some leftovers or half a pie. At first, I just thought this was my mother being gracious and polite. I later realized that she had a sense of children in need of a good meal, clean clothes, or a kind word.

All that changed again as we entered junior high. We started taking classes with serious names like Algebra, Latin, and Chemistry. We learned that atoms were the building blocks of everything, and they behaved according to very specific rules of plusses and minuses and energy levels. We learned that the electrons in an oxygen atom – typically eight of them – were all alike, but two of them occupied one level and the other six occupied a higher energy level, and never did the two levels mix. And then silicon, for example, had another energy level occupied by another bunch of electrons. And we saw it play out as the girls in our own grade suddenly had nothing to do with us, seemingly superior in all things except gym class, where they suddenly were unable, unwilling to do any number of things and regularly brought notes excusing the from this day and that day – but they still seemed to suddenly separate from us boys. That now put Bea, in the class ahead of ours, two whole energy levels ahead of us, completely beyond our ken. And we also learned that elements with full outer electron levels, like helium and neon, the noble gasses, did not lightly surrender electrons to form bonds with other elements, while elements like carbon, tin, and lead were quite quick to surrender their outermost electrons to bond – even with multiple elements. It seemed that Bea was not exactly a noble gas.

But at the same time, I started to see the kids from the neighborhood stacked up against their contemporaries, their equivalents. Soon Bobby was on a vocational track. I was clearly on a college track, and Bea was somewhere in the middle. Bobby was not only good at all the sports we played in the neighborhood, but he excelled at just about any that he tried. Whereas my neighborhood prowess resolved into proficiency at skills but less than dominance at matters of brawn. While I still saw Bea through my own particular lens, I could also now see that the way she stood out from the neighborhood kids was more about her age and gender. When in a group with girls her own age, they sparkled as a class, but few stood out above the others.

The three of us did not lose touch in high school, but the touches grew faint. Bobby and I were close after school, but we had nothing in common in classes or classmates. I passed Bea in the hall, and I still enjoyed the status of neighbor and brother’s friend that allowed me a nod, a smile, a look of recognition not bestowed elsewhere, but Aphrodite, in a cloud of similar Aphrodites, was categorically out of reach, escorted by some face-sucking upper-class Hephaestus who gravitated toward pinning her up against her locker.

As Bobby was drawn deeper into the trade school vortex, our after-school conversations revolved more and more around whether he should go into electrical or diesel mechanic trades. I couldn’t care less, but I gladly applied my burgeoning knowledge of the classics, humanities, and economics to the question of whether it’s better to work in a field that would always be there or get into a field that has demand for more specialized skills. I plotted supply-and-demand curves and Bobby pondered which line might be “electrical.”

Bea graduated a year ahead of Bobby and me, and she followed her older sister into secretarial school. The following year, she was planning her wedding to a fellow that owned the bowling alley across from the secretarial school. Bobby and I were going to walk together at graduation, and I finally learned what the grapevine had meant when Ronnie was graduating so many years earlier. Bobby would be entering the Navy in August, and I would be entering the state teacher’s college in September, though I was resolved to qualify myself as anything other than a teacher upon leaving said institution.

In many ways, that summer was a crowning glory to the relationships that we had built in the neighborhood. We were in our prime of life and we anticipated that prime lasting for many more years.

We occasionally saw each other around town when we would be visiting our folks, usually around Thanksgiving and Christmas, sometimes Memorial Day or Fourth of July. Four years later, I was graduating from the state teacher’s college, Bea was a married woman, and Bobby was getting married to a woman he had met while stationed in Japan. It was a small affair at the American Legion Hall. I met Bea’s husband for the first time. His name was Al, so Bobby and I took great pleasure in referring to him as “Bowling Al.” I danced one slow dance with Bea, and enjoyed every moment of it, but I was also glad this was not my fate. I gave Bea my business card with Centennial Mutual Life Insurance, in embossed letters followed by my name and my title, ‘Actuary,’ in black type. Tilting her head gracefully, Bea read the card and said sweetly, “So, you sell insurance?” I said, “No, I’m an actuary. I calculate statistical probabilities of every possible event under the sun.” She nodded, “Oh,” and then said with a puzzled look, “So, you sell insurance?” Apparently, that tender moment caused some strife between Bea and Al. They were heard in loud tones on the way out at the end of the night. Bobby explained their relationship to me after they drove away.

“You mean he hits her?! He hits Bea?!” I exclaimed. Yes, I had been drinking. It was a wedding. But armed with my exclamations, I expected Bobby to share my outrage. Looking into his face, I perhaps saw for the first time that he knew so much more about tradeoffs of pain and passion and promise than I had ever contemplated. In that one moment I felt the weight of vows and the ephemera of human frailty. “But, Bobby,” I said quietly, “you said he hits her.” Just six months younger than Bobby, I realized that he was now years ahead of me in terms of living real life – marriage, financial independence, choices I had yet to make. And even as we were growing up, he was making choices and fighting battles I barely understood. I had only seen the stable parts of his life and those of his siblings. But it was the unstable parts where they cowered together in fear of their father’s drunken temper or their mother’s mood swings and psychotic episodes. I realized in a moment that my mother’s mercies may have been so much more substantial in their kindness in those tough days than I had ever recognized.

Bobby explained, “Yeah. I’ve talked to her about it. I says, ‘Do you want me to come over there and rough him up?’ She says no. I says, ‘Do you want me to come over there and talk to him?’ She says no. I says, ‘Are you safe? Do you want me to get you a gun?’ She says no. She says to me, ‘I can take care of myself. I can take care of myself.’ I says, ‘Are. You. Sure.’ She says, ‘Yes.’ So, I’ve done what I can do. I have to respect her wishes at this point. She has made her choice. She knows exactly where she draws her line.” That was it. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but, clearly, it was settled. And then Bobby and his new wife went back to Japan where he was stationed.

Three months later, I got a call from her. Her voice came across the line as high and nervous. “It’s me, Bea! So how are you doing? How’s the job?”

“Good! Ho—”

“Did you say you can draw up a life insurance policy for me?”

“Well, no. Remember, I’m not an agent. I can’t write policies.”

“Well, tell me this about that: If I wanted to take out insurance on my husband, would he have to sign the policy?”

“If the policy was written on your husband, then, yes, he would have to sign–.” Click.

I was surprised when she called a second time, two weeks later. This time her voice was shaky. “He hit me. I told him I was hearing voices in my head, and he hit me.” She sounded like she was crying, “And he yelled at me, ‘Snap out of it!’”

I responded logically, “You need to find a safe place you can go to if this happens again. And you need to start documenting his abuse. Can you do that?” I thought nothing of the fact that she was calling me at my office in the afternoon.

Sniffling, she said, “Yes, I think I can. You think a month is enough?”

I didn’t notice her question at the time. I continued my own line of thought. “The next time this happens, you have to go right to the police. Promise me.”

She called a third time, panicked, this time at 9:00 in the morning. I couldn’t make out all her words, but I said I would come right over. She gave me her street address. I found her on her front step in her bathrobe very agitated, nervously chewing on her lower lip to the point of bleeding. I went inside. It was a horror scene. Whatever led up to it, it was clear that it ended with one sharp blade probably brought upward from his belly to his chest and he probably bled out slowly. I called the police and told them to bring an ambulance from the psychiatric unit.

We sat out front on the steps until they arrived, one police patrol car, one ambulance. I held Bea’s bloody hands as she shook. She continued to chew her lower lip. When she saw the ambulance, she stood and began shrieking, “No, don’t let them take me where they took my mother! Don’t let them take me where they took my mother! Don’t let them take me where they took my mother!” I wrapped my arms around her and held her tightly.

*

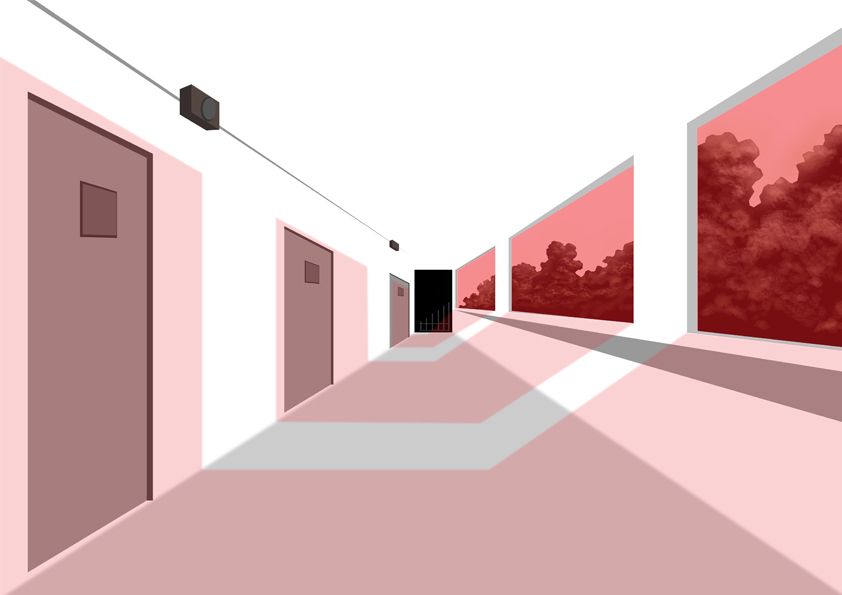

I went to visit her, just as I had every Wednesday and Sunday for the last nine weeks. I showed my I.D. at the security desk and the buzzer sounded. I passed through the heavy door. The glass in the door and the side panels were reinforced with wire. My footsteps echoed down the long white hallway. The muzak played “The Girl from Ipanema.” There was a sterile but soothing baseline hum of people going about their business, making rounds, and in some cases, wandering aimlessly. The quiet was occasionally interrupted by the clatter of metal trays and utensils or the dull thud of slamming drawers or doors. I passed an open door revealing a gurney equipped with leather straps. The solarium, as they called it, consisted of a seating area perhaps fifty feet by twenty open to the hallway on one side and a wall of windows on the other. I found her sitting staring out a window. I moved a chair closer and sat down. I glanced over at her. Her expression was calm and relaxed. Across the solarium a man began talking to himself, “Stay out. Stay out. I know why you’re here. . .”

“Ignore him,” Bea said quietly continuing to stare out the window.

“How are you doing?” I asked just as quietly.

“I’ve never been better.” Her voice was devoid of any sarcasm. She shook her head slowly, subtly from side to side, all the while gazing out the window. “I think they might let me out next week.”

“Do you think you’re ready?”

“I’ve been ready.”

“No more voices?”

“There never were any voices.” She looked at me. “You probably don’t understand how the child of an alcoholic and a Schizophrenic looks at the world. We only have certain tradeoffs available to us. There’s a certain price you’re willing to pay to get out of that house. And when your husband beats you . . . there’s a certain price you’re willing to pay to get out of that house. I’ve just been trading up each time. And you learn the rules of the people who are in control. And you learn they just want their power, and they don’t want to be bothered. So – you just don’t get in their way, and you don’t complicate their lives. You stay in a neat little box. I know the rules.”

“Are you telling me you were never hearing voices or having hallucinations?”

She looked at me and spoke even more softly, “There are certain things I won’t say in here.” She looked back out the window. “Maybe I might say them when I’m out.”

A heavy-set woman in white approached the man who had been sitting to my right, motioned to him, coaxed, “Mr. Conrad,” and escorted him out of the solarium.

Without looking at me Bea reached over and touched my sleeve. Visions of watermelon wedges on the front stoop flashed through my mind. Just as quickly, she took her hand away. Then, looking at me and searching my face, she said, “Each morning I ask God to forgive me for the sins I committed yesterday, and give me grace to deal with today. But I know I’m going to sin again today. Just like everybody else.”

The radiator directly in front of me began a loud release of steam that slowly trailed off.

She went back to gazing out the window. “We’re all trying to get to the same place, aren’t we? And I’m a lot further along today than I’ve ever been.” She looked over at me and gave a faint smile. The late afternoon sun was now low and shone directly into her face. As she turned back to look out the window, the light hit her eye from the side and exposed its inner workings – cornea, iris, pupil, lens. This is the same frail girl I’ve known all these years, fearfully and wonderfully made, long-suffering, capable of great and terrible things. So many times I imagined heroic rescues from the indignities of the school yard, the hallways, but I had no idea what she – or Bobby or Timothy – were really dealing with.

I wrote to Bobby in Japan each week while Bea was in the hospital. He responded sporadically. That night, in addition to my usual update on her appearance and her attitudes, I wrote and asked Bobby whether he thought that Bea’s illness was real. His response was unusually prompt and detailed. He wrote, “Here’s what Bea and I talked about. #1. It’s wrong to kill a man out of malice or carelessness. #2. It’s not wrong to defend your own life. #3. It’s wrong to lie to doctors, unless to defend your own life. She did not want to do wrong, but she was ready to do the least wrong thing.” I can’t say I followed all the logic. But that was the last time I corresponded with Bobby. He sounded happy, like he was in a good place. They were going to start a family.

Bea was released the next week and went to live with her older sister while she sorted things out.

And, so, my blessed obsession came full circle; what I never thought to pray for as a child, I am now compelled to pray for daily.

*

I ran into Bobby’s father a few years ago. He was working at a Cumberland Farm down the street from my parents. I didn’t recognize him at first. He had been drunk most of the times I had seen him as a kid. He was now neatly dressed with his hair slicked back, though it was all grey now. He recognized me. He said it was good to see me. He rang up my purchase. He asked what I was up to, where I was living. I gave him the quick version. Then he looked at me with a serious face and said, “Did you hear about Bobby?” I hadn’t heard anything about Bobby for years. “He was living in Japan. He got a liver infection.” He started to break up. “He and his wife were so happy. He passed away two months ago.” I hugged a man I had never hugged before, though he was like a second father to me. He had watched me grow up alongside his own kids. He cried on my shoulder. No doubt he regretted his own weakness just as I regretted my own blindness. With that hug in a Cumberland Farms, we buried my best friend.