Parts is Parts: Part One

My thoughts flew from my mouth before I could catch them at the commonsense muscle Uncle Archie enjoyed reminding me was supposed to keep us all from saying embarrassing things. He also reminded us how that stop-gap muscle was particularly under-developed for many in our family, including himself on occasion. It was too late to stop myself, and in this case, I don’t think he would have minded.

“My uncle is not a cannibal!” I screamed at the faces of two women in the booth behind us, half-chewed scrambled eggs flying from my lips. There was no rule against defending the family with your mouth full.

“They were talking loud enough for us to hear exactly what they were saying,” I told Dad in the car after he’d shuffled me out as fast as he could toss a twenty at our stunned waitress.

“Now listen,” Dad said, trying to console me, “do you really think those old biddies really believe Arch is a cannibal?”

It sounded outrageous, of course. Weird? Yes. Cannibal? Not even him.

“They just like the sound of their own gossip, right? If Arch was really partaking of the forbidden flesh, do you think he’d be taking an ad out like that?”

Come to think of it, I didn’t remember either of the women actually using the term cannibal, but when one had asked, “What’s he doing with all them parts?” and the other had laughed, “Probably making soup!” and they’d both just giggled, all of it loud enough for anyone to hear in Rally’s Café, which was crowed all the time, let alone this being the brunch hour on a Sunday, all I heard was the word cannibal being broadcast over the sizzle of sausage and small talk about the morning’s many sermons. I had to defend my uncle’s good name.

“They called me an anthropophagus?” Uncle Archie yelled, obviously insulted. “Those blamed busy-bodied biddies!”

“What’s a biddy,” I finally got around to asking, especially since I’d heard the word twice in an hour. I’d learned the phrase “busy-body” years before.

“Those women are!” he said.

“And that other word? Arthur-pegasus?” I asked.

“Anthropophagus, boy!” he yelled. “We won’t stoop so low as to stray from the Greek on such illustrious terminology,” he beamed. “Anthro – meaning man, phagus – meaning to eat, man-eater, or cannibal as the less etymologically refined might attempt in their lesser vulgar vernacular.”

He was on a roll.

“How about bar-be-que for supper,” he suggested. “I’m buying!”

This episode was making me question what it was about Uncle Archie and body parts? Sure, “parts,” as he generically called them, were popular items at the Odditorium store: jars full of floating eyeballs and unidentified brains and farm animal fetuses, bones from out-of-business medical labs and schools, not to mention that full hanging instructive skeleton of the last man hanged in Kentucky. That item belonged to me know, having earned it for keeping my mouth shut a few years earlier during the cryo-tank incident. All of these were popular, but I wondered why he seemed to love them so much, apart from them bringing in regular good money.

About lost limbs and such he’d say, “You can’t take it with you, especially if you lose it, but you might can make a buck on it before you go.” And in our case, a little cash might make people think twice, when before they never gave much thought to the parts they were having lopped off for whatever reason. These attitudes were quickly changing around Labortown and the county.

He’d taken out an ad:

Got parts? Have an amputation

procedure coming up?

Good money for specimens. Call Archie.

“Why go out finding them when they’ll come to us?” he figured.

“Come to us to what?” Dad asked, afraid of the answer.

He pointed to a long shelf unit, lined only partially with wet specimens. “That shelf don’t fill itself, brother,” he said. “We’re low on inventory and that stuff’s getting harder to acquire. It don’t grow on trees.”

“I’d like to see that,” Dad said. “What do you expect people to do, hop by with their severed foot in a box? Leave it on the porch for ya?” he asked, laughing.

“Oh, if it were that easy,” Uncle Archie mumbled. “If we were back during the Civil War, like when our great-great-great uncle Doc Felix was in business, we could’ve been rich. He chopped arms and legs off by the wagon load.”

I hesitated to mention how due to the mass availability of all those body parts, that the value he referred to would have been near nothing. I opted for a flippant, “Only if we maybe had a time machine.”

Dad questioned the legality of receiving amputated body parts, even if they were from the original bodies, living or otherwise.

“I done my research,” Uncle Archie claimed proudly, which in the days before good internet usually meant he’d burdened the county librarian for some help. “Did you know there’s been an average of 457 amputations per year in the last decade in Kentucky alone?”

Dan looked bewildered.

“Yep, and there’s no law against claiming your own parts in most states, unless the original issue with the amputation was bacterial or viral in a way that might spread.”

Dad didn’t mind all the strangeness. He was only a shade less odd than Uncle Archie. But this was a new shade of weird.

The calls were immediate.

A woman scheduled for a below the knee amputation due to diabetic arterial thinning, called up a week before her procedure. She’d gone round and round with her insurance, but they’d only cover 95% of the entire thing, which still left her potentially owing plenty. She figured she’d supplement the costs by promising Uncle Archie the leg. I heard her cussing him through the phone when he quoted her only $200 for her soon-to-be apportioned appendage.

“Ma’am, that’s the best rate I can offer right now. It’d be more if it was below the hip, but that’s not up to you or me either one, now is it…well, I guess that’d be double…but you don’t have a problem with above the knee, I reckon, do you…well, I suppose the doc would have said the whole leg had to go then if that was the case, but he didn’t…any tattoos?…Ma’am you gotta understand…I don’t just lay this stuff out dry on a table, the glass containers are huge for legs and arms and brains, it’s expensive…Yes, I know that’s my problem and not yours…Well, two-fifty’s about the most I could do…right, I know that’s probably not enough to pay for a bandage on the stump…hello…hello??”

“That went well,” Dad joked.

“I knew it. People think their parts are worth more than they really are. Hell, back in the day you could get a whole fresh body for ten pounds in London.” He sounded like he knew firsthand.

“How far back in the day we talking?” I asked.

“So I’ve heard,” he said. “Way before my time, boy. Like I said, I’ve done plenty of research.”

“This how Dr. Frankenstein started out?” I wondered.

“Probably. He was a grave robber like the rest of them,” Uncle Archie figured. “He wasn’t afraid of getting his hands dirty. I’m surprised he could afford as much raw material as he went through before getting it right.”

Dad wondered how Uncle Archie was coming up with his baseline payouts.

“These days, if you could harvest every organ and tissue from a body, it’d be worth about $165,000. That’s organ transplants and science use. All the way down to the bones and marrow. Skin. Nothing left but stinky guts.”

What in the world was I hearing?

“The body’s not worth ten bucks chemically speaking. That includes the little bit of gold spread through the body.”

I kept silent.

“Maybe those old gossips you told off at the restaurant had the right idea. Ever wonder what a good human steak goes for on the deep black market?”

I was all in. I never imagined I’d be hearing such things. “But never mind all that,” he laughed, changing the subject.

“I’d like to quadruple my investment. Let’s say we get a good foot in here, for like a hundred bucks, add fifty for the container and fluid, I don’t think five-hundred’s too much to ask, do you?”

Dad shrugged. Uncle Archie looked to me. I shrugged.

“See? We’re mining our own commercial niche here. We’ve got to find the sweet spot. Not too cheap, not too proud.”

Only Uncle Archie could normalize a conversation about marketing body parts.

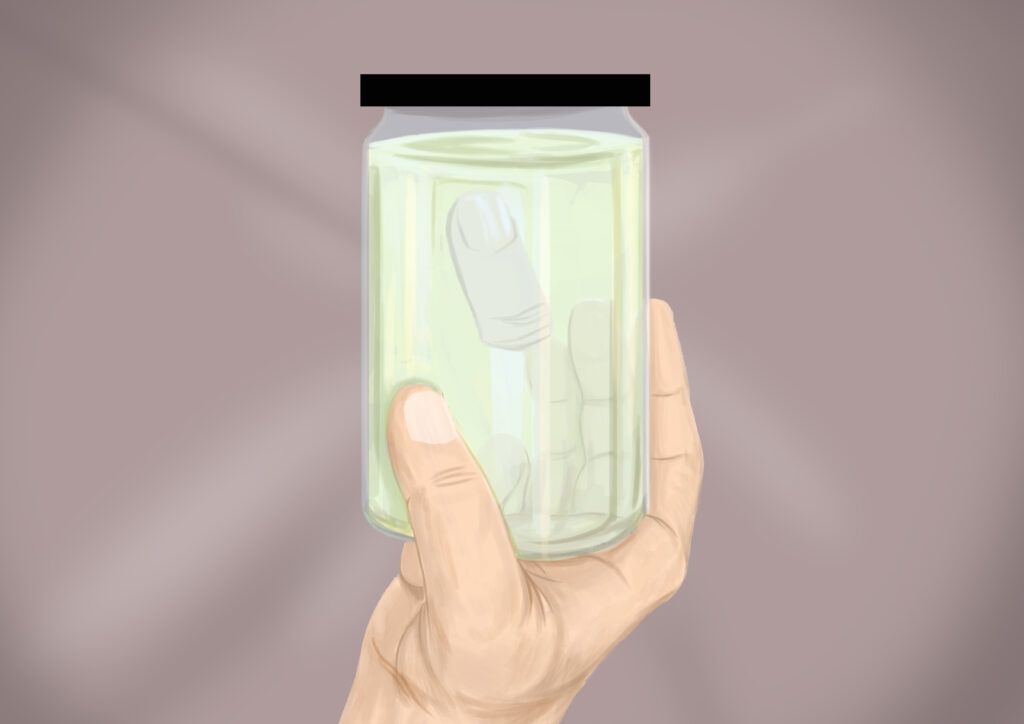

Ricky Sams called up one day. I was working. He didn’t say hello. Didn’t ask for anyone in particular. Just asked, “How much for a thumb?”

I told him to hold on while I looked at our inventory and the logs.

“We don’t have any thumbs in stock right now, but I know we’ve had one or two,” I told him, “and I don’t see mention of what those went for.”

“No, I’m not looking to buy one, buddy,” he said with a grunt, “I’ve got one to sell ya’ll if you want it. Fresh.”

I was intrigued. Uncle Archie or Dad handled these conversations, but I was the only one around.

“Fresh?” I repeated.

“Fresh. Yes, very,” Ricky grunted, as if in pain, “as in sawed off twenty minutes ago.”

Now at this point the conversation could have gone down various paths. I tried asking all the right questions as per my having eavesdropped on plenty of negotiations by now.

“Yours? Or someone else’s thumb?”

“Definitely mine.”

“Accident?”

“Yep. Power saw.”

“Clean or mangled. Quality matters,” I said.

“About a seven out of ten,” he said.

I appreciated the specificity.

“Sounds like it’s in good shape, why don’t you go get it worked on?”

“I did call the doc,” he told me. “Said it weren’t no good anymore after Gemini chewed on it.”

I had so many questions.

“I thought you said it was in good shape. And who’s Gemini?”

“Gemini’s my wiener dog. He took off with it before I could grab him. He’s half wild anyway. And even though he ain’t got any teeth, the doc said he’d probably gummed it awfully hard and done a lot of damage on inside. That’s why I judged it a seven. Before Gemini mouthed all over it it was probably a good nine.”

“Shame,” I muttered. “Got it on ice?”

“Yep, more or less. I hadn’t finished my grape slurpy yet.”

I did what I figured Uncle Archie would do. I lowballed the fella.

“Fifteen dollars,” I said.

He hesitated a beat.

“Fifteen dollars! Hell, man, the fingernail’s still on it! The blood ain’t even dried yet it’s so fresh!”

“Fine! Twenty bucks.”

“I heard about a guy who lost his thumb and got fifty-thousand from workman’s comp!”

I hear Uncle Archie talking, but with my voice.

“I’m sorry, did you think you’d called up workman’s compensation? Oh! No wonder you thought you were gonna get rich! This is Archie’s Odditorium and Gifts, Mr. Sams. We can always use a good thumb in the collection, but twenty’s it.”

He hadn’t hung up on me, so I knew we were still in the game. He grunted, maybe in pain, maybe in frustration.

“How long y’all open?”

“Close at five, but we’ve never kicked anyone out for really shopping.”

I had the thumb swimming in clear alcohol in its new glass home long before Uncle Archie and Dad got home from the flea market. The jar was sitting on the checkout counter. I already had a price on it: $120.

I explained everything from the beginning.

Uncle Archie stared at the jar. Picked it up, let the sun shine through. Eyed it as if it were his own lost thumb. He sighed and shook his head.

“I’d have got it for fifteen,” he grunted, looking at dad in that sort of how-are-you-raising-this-kid way.

“I doubt it,” I shot back. I knew he was joking in his own way, but I guess the humor had left me. I was pretty proud of what I’d done.

Dad noticed my tone and jumped in. “Looks like he handled things pretty good, didn’t he, Arch?”

I’d worked hard for that thumb. I’d negotiated something special. A real piece of someone, something they’d lost and handed over for an agreed price. An extension of importance – the thumb of a hand – that we’d then sell to some other curious customer. I wasn’t taking it lightly, even as a fourteen-year-old kid.

Uncle Archie said, “I like the price you put on it, though, boy. Tell you what – if you can get $120, I’ll half it with you. I’d have probably put $90 on it myself, but I like your gumption.”

Parts is Parts: Part Two

Uncle Archie’s second newspaper ad brought even more attention:

I Need Your Body (Parts!)

Accident? Make lemonade!

Contact Archie’s Odditorium

for the best rates.

Our wet specimen stockpile was accumulating. Plus, more people that usual were coming by to see the stuff. How can you resist visiting a place that’s literally asking for body parts?

People assume you can’t claim your own “leftovers” from a surgery. You can in most states, as long as the amputated / removed part isn’t diseased in some way that would make it a hazard to take home. We had a new foot in a jar, a thumb, a set of tonsils, multiple extracted teeth, that woman’s leg below the knee. The place was smelling stronger of formalin and alcohol by the day.

When Mr. Jacob Farmer’s last will and testament was read and included Uncle Archie, stating how the Odditorium was to get Mr. Farmer’s heart, lungs, and liver, the widow Farmer about followed Jacob on she was so surprised and upset over the news.

And it wasn’t like Uncle Archie and Mr. Farmer had it all planned out. They were friends, sure, but until he was notified of his friend’s wishes, the subject of organ donation had never come up between them.

“I think this is one of Jacob’s last jokes,” Uncle Archie thought, “Either on me, or his wife Rita, or both of us. He liked to play up much she didn’t like me.”

Though she threatened to hold the whole thing up in probate court, she finally realized it wasn’t worth the court fees and came to terms, after a few hours of therapy with her Christian counselor, that even though someone else would technically own Jacob’s heart, lungs, and liver, that those items weren’t really her dear husband any longer. Besides, she’d always be able to visit those personal items as long as they were still on the shelf for sale.

Uncle Archie returned from a grocery run one afternoon. Rather than heading for the kitchen in the house he came to the store with a couple of heavy looking grocery bags.

“Take these to the back workroom,” he told me. “You’re gonna love what I found.” He was always assuming I was on the same page as him when nobody else would be.

Every plastic bag was full of what looked like three of four rock solid frozen chunks of meat. I figured they were small turkeys or chickens. He regularly found “deals” at the butcher, so no surprise. He’d struck gold again, I guess. By the time he was done, we had five bags on the stainless-steel worktable.

He pulled one out. It took both hands to hold it. He handed it to me. It was a good three or four pounds. I thought it might be a liver or other organ. I read the label: bison heart. It was a week past its due date.

“Brock the Butcher called, said he had a deal on organs. All the bison hearts we want. I took all fifteen of them,” he said proudly. “Only five dollars each. They were twelve a piece fresh!” he said as he was filling a large steel pot with lukewarm water.

I had questions. Why’d Brock the Butcher, as only Uncle Archie knew him, as if he was some professional wrestler rather than just Mr. Brock who ran the butcher shop, have fifteen bison hearts? And also, why were they still five dollars each if that much out of date? And I wondered, too, if Brock the Butcher had called anyone else up in town bragging about having fifteen stale bison hearts to unload cheap, but not free?

I’d unwrap one and he’d plop it down in the water and let it sink to the bottom. We did six. Apparently, fifteen would have been overkill at one time.

The hearts softened up. The water turned the color of week cherry Koolaid. Little globs of fatty tissue floated. The big artery stumps loosened and stuck out. Once they thawed they were obviously giant hearts.

I put a heart each in clear three-quart jars full of 70% alcohol. I had to drop them in gently, so the lower tapering portion of the heart rested at the bottom of the jar and the sides pressed to the jar walls and the aorta stuck up from the top. Perfect.

Uncle Archie attended 11 am mass for no reason one Sunday. Instead of sitting with us, he “found the only seat left” next to the new orthopedic surgeon in town. I hung out nearby while he tried talking Dr. Landry up during coffee hour.

“Looks like rain, huh, Doc?”

She’d just nod and sip her tea. She drank tea during coffee hour.

“So, Doc, what’s the amputation business like these days?”

She suddenly had to go, she said, “I think I left my curling iron on. And the stove.”

“C’mon, let’s get outta here,” he huffed. “The Baptists are only just now letting out and I know where the county coroner has lunch.”

We weren’t without our share of crank callers and jokesters once the ads ran.

You know how you mother would threaten to call up Santa Clause in November when you were “acting like a little heathen?” A couple of local mothers started call Uncle Archie up and threatening to donate their dumbass kid’s brains to the store – immediately! – if they “didn’t start acting like they had some sense!” The kids would be crying and begging in the background just like you would back in the day when you thought Santa Claus was checking in with his magic crystal ball as your mother was talking on the phone to the North Pole.

“I bet you can do better in that math class! You ain’t no D student!”

The mothers would threaten, “Boy, I’ll have Old Archie the parts dealer come by tonight when you’re asleep and saw you head right off! All your school friends’ll point and laugh at you sittin on the store shelf next time there’s a fieldtrip to see that old man’s crazy shit!”

Uncle Archie’d play along until they got personal like that. He’d hang up mumbling about not being available as Labor County’s next mythological meanie.

A woman – she didn’t identify herself – called up wondering if we’d pay good money for a certain private appendage belonging to her “lyin, cheatin, jobless, good-for-nuthin, piece of you-know-what” husband.

Uncle Archie asked if she was referring to what he thought she was referring.

Yes, she said, the very article.

This was new territory for sure.

He asked if the “member was dismembered already,” so to speak.

Not yet, but any day now. Bastard’s been on a bender for two days already. He’s bound to come back eventually. He’s got to fall asleep eventually, right?

“Uh huh,” was all Uncle Archie said.

“You gonna want it in a jar or just wrapped in some paper towel?”

It was usually Uncle Archie getting hung up on, but this time he couldn’t hang up fast enough.

“If she calls back,” he instructed, “refer her to Sheriff Doug. I’m going to lunch, boy.” He looked a little green around the gills. She never called back.

Sheriff Doug Highers came by a week later. That was no big deal. He came by every few months to catch up with Uncle Archie. He liked fossils. Especially dinosaur bones. He liked using them in his Sunday School classes when he taught Creationism. Uncle Archie reminded me that we weren’t in the business of socio-politics. He said, “If someone wanted to use something they bought from us to claim aliens founded Labor Town, I wouldn’t stop them. I might even listen to what they had to say.”

On this occasion, however, he immediately asked Uncle Archie to step outside on the porch “for a word.” That sounded awfully official. Not friendly like their usual visits.

Come to find out, the Sheriff had worked all weekend on a new domestic case involving Sue and Randy Barker. Seems Randy’d woken up with Sue hovering over him with a new Ninja-roni Cleaver like she was about to dive into battle. He hadn’t gotten away unscathed – she’d flayed his left nipple off – but he had grasped out and gotten hold of her hands just in time though he was a very heavy sleeper, especially after a two-day cheating bender. It’d been obvious where she was headed with the new purchase. She’d planned to permanently nick him where it counted. He’d scrambled away and locked himself – naked, of course – in a bathroom with his cellphone where he called 911.

During interrogation Sue had claimed Archie had put her up to it, which, as weird as things could get, was ludicrous in the sheriff’s opinion, but worth checking out since even he’d read the ads in the paper.

They came in off the porch still talking.

“Hell, she didn’t even give her name when she called, Doug,” Uncle Archie told the sheriff. “I even hung up on her. Ain’t that ‘NO’ enough?”

Doug said that was enough for him.

“Oh, by the way,” Sheriff Doug said, pulling a small clear evidence jar from his inner coat pocket. “The ER doc said there wasn’t enough to sew back on and Randy said he didn’t want it since it’d remind him of what almost happened.”

Uncle Archie raise the specimen jar up to the light. A pinkish and fleshy oval swam around in the fluid.

Doug asked, holding back a laugh, “What’ll you reckon the market will bear on a man’s nipple taken in violence?”

Uncle Archie gave it some thought.

“I don’t know,” he said, handing the little jar to me. “I don’t think I want to find out. Why don’t you put that in the permanent collection, boy.”