Meg Chen’s sister Amy refused to believe that Paul McCartney was still alive.

“But we just saw Paul play on tv,” my best friend Meg told her. We had watched an interview with The Beatles and Paul, with his impish grin, was very much alive.

“That man was a replacement. Paul is dead. He died in a car crash. believe me,” Amy told us, taking her framed photographs of Paul and placing them face down beneath her bed.

“What’s your proof?” Meg asked. She was sitting on the floor, her legs crossed in a lotus position. After the Beatles visited India the year before in 1968, she decided to practice yoga.

“Listen to end the of Strawberry Fields. You can hear John say “I buried Paul. And you know about the cover of Sergeant Pepper.”

“No,” I was curious and felt I had missed a momentous clue. “What about the cover?’

“Paul is actually dead. His bandmates are propping him up so he can stand. Look at the wreaths of flowers too. Those belong to a funeral.”

“What a bunch of crap,” Meg said. “Where is that album? I want to look at it now.

“No way. Last time I lent you my record you scratched it.”

Meg made a hissing sound that Amy ignored. She was sixteen, three years older than us, and attended Julliard to study dancing. She was tall, lithe and wore her long hair in a bun. She was beautiful in a way that Meg, who was short with stout legs and a chubby face, must have envied.

Amy reached over to her night table in order to examine a black beret that looked exactly like the same beret that Yoko One liked to wear.

Amy claimed to have once seen Yoko Ono at The Dakota, and that Yoko smiled at her.

“Paul is not dead,” Meg said loudly. She was clutching her fists and for a moment I thought she might hit her sister. Meg, I had learned that year, could grow very angry very fast.

“The Beatles are over anyway,” Amy said as her telephone rang. “Now scram, you brats,” she cried before she picked up the receiver.

“Ugh, it’s her stupid boyfriend Mike,” Meg told us as we walked down the long hallway toward Meg’s room. “He’s the one feeding her all this Paul is Dead stuff. He’s a total Bob Dylan freak and hates the Beatles.”

Meg’s home was a full-floor apartment on The Upper East Side. No one asked you to take off your shoes when you entered – you immediately knew this was a given. The walls were covered in paintings of shimmery landscapes from China, mountains and trees with gold frames that glittered even in the dark. One glass cabinet held ceramic plates that Meg claimed The Metropolitan Museum wanted for their collection. The apartment always smelled of tulips which Meg’s mother kept in vases that she bought from a floral shop that specialized in flowers shipped directly from Europe. No matter how much traffic was outside, their apartment was always completely silent. It was as if it existed in another universe where sound was abolished. Until Meg and Amy started playing their rock records.

The Chens were the only wealthy family at our school with a missing father. When I asked Meg about her father all she said was that he was in Australia. Meg had left China when she was an infant and grew up in Sydney. But Mrs. Chen, Meg’s mother who worked for Sotheby’s art auction house, was transferred to New York City. Meg arrived late at our school in October, I’d never seen such long shiny black hair on a girl my age. Actually, I’d never seen an Asian student, much less an Asian student with an Australian accent. Most of my classmates were from wealthy Protestant families that belonged to clubs that didn’t allow my Jewish family to be a member. There were only three Jewish families in my grade. Once I heard one mother say that Rachel Cohen’s mother was “pushy.” Her friend responded that “they all were pushy.” They’re talking about me, my family, I realized. That’s their code name for Jews. Pushy.

We could only play Amy’s Beatles records when she was out with her friends. We played “Strawberry Fields Forever” but couldn’t hear anything about Paul dying. Our favorite song on The White Album was “Back In The USSR”which we danced to so violently, jumping up and down on the floor that the neighbors downstairs complained. Meg was in love with John and I was in love with Ringo. If we both loved the same Beatle, we couldn’t be best friends.

Meg and I bonded over our love of not only Beatles but also with Hot Chocolate from Serendipity, ice-skating at Rockefeller Centre, visiting the dinosaurs at The American Museum of Natural History and our mutual hatred of almost all the other girls in our class.

“How did you ever survive here?” she asked in her twangy Australian accent.

“You’re the best thing to ever happen to me,” I told her. She grinned. Meg had perfect teeth. Mine were covered in braces. Maybe Australia had wonderful dentists.

“Meg can’t be her real name.,” my mother said to me and my father one night at dinner.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“She must have a Chinese name.”

My younger brother placed his fingers by his lids and pulled them upwards so they were slanted.

“Screw you, Nathan,” I said. I, not Nathan, was sent to my room.

Since I didn’t want Meg to be anywhere near my brother, we mostly hung out after school in her apartment. Her mother was rarely home since she often attended auctions all over the world. An elderly housekeeper cooked and cleaned for the girls, but Meg insisted she was not their babysitter.

When Amy wasn’t home, we would ransack her record collection. We decided we hated the name Led Zeppelin, that Pete Townsend of The Who had a really big nose but Keith Moon was adorable. We found the photos of Paul that Amy had hidden beneath her bed and kissed him on top of the cold glass frames. We also found her plastic bags of marijuana which looked like something my mom would use to season a roast.

“Have you ever tried it?” I had asked Meg when we first discovered her sister’s stash. Meg furiously shook her head.

“Never. Amy always has to buy a whole bag of Fritos because she gets the munchies. No way will she finish Julliard.”

Amy wanted to be a ballet dancer. All Meg and I wanted to do was visit Narnia.

We had both read The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe at least four times. Meg was sure that Narnia really existed. Unfortunately, her mother did not own a wardrobe but Meg was convinced we just had to find the right door. Her apartment was filled with so many doors. Doors to the dining room, closet after closet, the bedrooms, the bathrooms, the living room, the kitchen and the laundry room. The fur closet, Meg thought might have a magic entrance. We pushed aside coats made of mink, fox, Persian lamb, and one which Meg said was from a leopard. Finally, reaching the wall past all those coats, we both shouted “Let us in, Digory!” Of course, we did not gain entrance into Narnia but we still persisted, banging on the walls until our palms ached.

Every weekend we had a sleepover, always at Meg’s apartment. Back then I was relieved my parents never telephoned Meg’s apartment, but now I wonder if they avoided it because they thought Meg’s family only spoke Chinese. We both slept in Meg’s huge pink canopy bed with satin sheets the color of pearls. Her walls were covered with glossy posters of The Beatles with a big red heart circled in red magic marker over John’s photos. Next door we could hear rock music from Amy’s room, and the laughter of her friends. We didn’t care. They were stupid girls who still were convinced Paul was dead. Meg and I were blood sisters. On our sixth sleepover, Meg took out a sharp penknife from her drawer that looked like the knife my brother used in Boy Scouts.

“Don’t be afraid,” she said as I backed toward the wall. “You want to be my sister, right?”

I remember girls at my sleep away camp who did this ritual but no one had ever asked me. I was always an outsider with the other girls. Meg was the first friend who really made me feel good about myself.

“Let’s do it,” I said, and didn’t even flinch when Meg sliced my finger and we rubbed fingers together

In school we were inseparable “The two Japs,” I heard Susanna Litchfield call us. I turned to her and said, “Meg is Chinese, you idiot.” Meg just laughed when I told her and said that Susanna had dandruff and such bad body odor that no one would sit next to her in class.

“Why don’t you invite Meg over some time?” my mother asked me one day. “We can order from Empire Szechuan.”

“Meg doesn’t eat Chinese food,” I said so sharply that my father put down his fork and knife and stared at me.

“Apologize to your mother right now,” my father said. “She is inviting your friend to dinner.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, but my mom and dad could tell I didn’t mean it. My brother smirked.

Later, my father, her told me to come into his office. He shut the door so hard that I felt as if it slammed into my chest.

“Leah, that was unacceptable. Your mother is under a lot of pressure. Grandpa is coming to stay with us for a while.”

“Grandpa!” I didn’t hide my surprise. “But he’s crazy!”

I knew I shouldn’t have said that about my grandpa but I was angry. He had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and my parents were really struggling to find someone to care for him full-time. My father’s face flushed with anger. He lifted his hand, and I was scared he would hit me

“How you dare call him crazy,” my father said, his voice low and deadly. “Your grandfather was a war hero. He saved hundreds of lives in the Pacific. He’s a hero, Leah. Say it.’ “Grandpa’s a hero,” I said, my voice trembling. “I’m sorry.”

I had seen his medals – my dad kept them in a fireproof safe in his bedroom closet. I also knew that my grandfather had volunteered to fight when he was forty. We had relatives in Poland who had died in the concentration camps. My mother told me this once and said never to talk about it again. It was as if their deaths were a curse that could return to haunt us.

My father left his office then, and I went into my room, where I couldn’t stop shaking. I had never seen my father so angry. Down the hall I could hear him speak to my mother. I was hoping she would knock on my door, but she stayed with my father. I promised myself I would be kind to my grandfather, and show my father I could be helpful.

When my grandfather arrived, it was difficult for me to imagine this shrivelled bald man as a war hero. Sometimes he wouldn’t speak for hours, but just stare out the window, clucking his tongue like a rooster. After a week, I grew used to his sudden rantings. He would call out men’s names: Harry, Jack, Ben, as if they were hiding somewhere in the apartment. He told my mother she was a very bad private and he would report her to his superior officer. When he was very, loud my father would give him a pill that made him look like a zombie with a weird film over his eyes.

I tried to escape by spending more time at Meg’s apartment. Amy had joined her mother in Hong Kong, and we had the apartment blissfully to ourselves. We were in Beatles heaven as we listened to Amy’s collection every day after school.

“I think I’m in love with Paul,” Meg said.

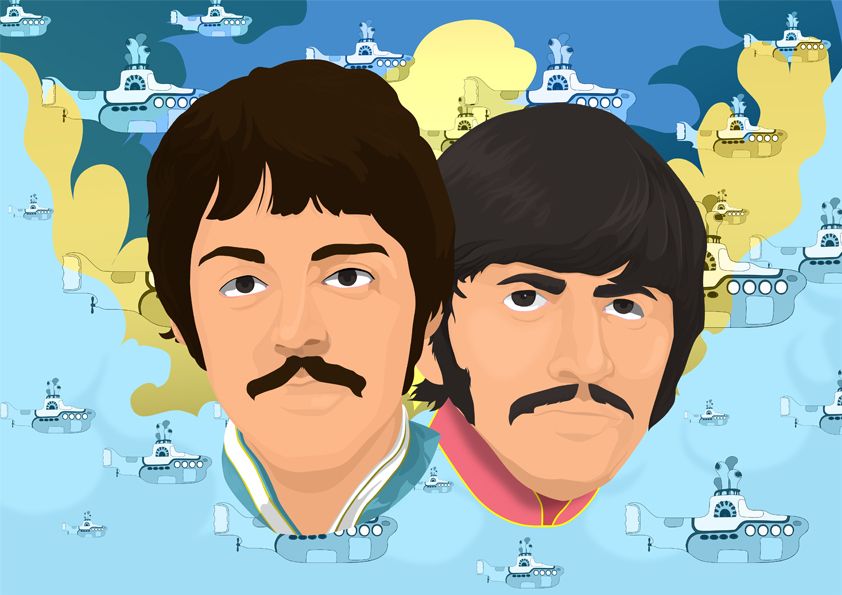

Meg’s change of heart came through a dream. Paul McCartney, dressed in the same powder blue military style uniform he wore on the cover of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, had floated down from the sky with a diamond ring and presented it to Meg on bended knee.

“You’re thinking of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and John wrote that song.”

“Doesn’t matter. They wrote everything together.”

I wasn’t going to argue that “Michelle” was written primarily by Paul McCartney. But the truth was I was getting tired of Ringo’s stupid jokes and Paul’s new beard made him look very sexy, and I was beginning to understand what sexy meant. We stole Amy’s photographs and posters from her bedroom and made our own scrapbook of Paul McCartney decorated with gold stars and the title PAUL 4EVER. There was a very young Paul in a leather jacket in a Hamburg nightclub. Paul in his adorable mop haircut and a suit at the Ed Sullivan show, bearded Paul in India, dressed in a tunic, kneeing before a wreath of flowers. Both Meg and I loved the photo of Paul as a wilderness man, traipsing through an English forest, with a tree branch in his hand.

When I inadvertently told my mother that Meg was essentially alone in her apartment, (the housekeeper seemed to have vanished too) she insisted that we invite Meg for dinner. My brother would be so annoying, playing basketball in the next room. And then there was my grandfather.

“Don’t worry,” Meg said. “One of my Great Aunts is like that. She tells everyone that she’s eight years old and only wants to eat chocolate cake.”

I begged my mother not to order Chinese food for dinner. My mother agreed and made spaghetti and meatballs. Grandpa had his dinner at five and was usually asleep at seven. Luckily my brother was away for a sleepover. Even my dad would be absent, attending a meeting at his law office.

“Just us girls,” my mother said soothingly. Meg arrived with a bouquet of roses.

“Thank you, Meg,” my mother said. “They are beautiful. See,” she said to me. “Meg has perfect manners. She should be an inspiration to you.”

I was annoyed at this remark, and Meg, who was helping my mother arrange the flowers in a vase, said, “Leah has perfect manners. When I first arrived at school, no one would talk to me except her.”

“I’m sorry that the girls were rude,” my mother said, frowning.

“I think, Mrs. Heller, that no one could figure me out. My Australian accent confused them. Was I an Aussie or was I Chinese?”

“And what are you?” my mother asked.

Meg shook her head. “I’m not sure, Mrs. Heller.”

I was embarrassed by this conversation. Couldn’t my mother talk about something else?

“An American,” my mother answered for her. “Right dear? You live in America now.”

Meg didn’t reply, but I could tell by the stern set of her mouth she wasn’t pleased with that answer. As my mother prepared dinner, Meg and I retreated into my room.

“Sorry about that,” I told her.

Meg shrugged. “Everyone always asks me those questions.”

“Do you think we can reach Narnia through my closet?”

Meg opened my closet door and pushed away my school uniforms which my mother ironed and hung on special velvet hangers. “I don’t think so,” she said. “Narnia, after all, is just in a book.”

I felt betrayed. I knew pounding our fists against the wall was a fantasy, but it was our fantasy. Before I could reply, my mother announced that it was time for dinner.

Meg dutifully ate the meatballs and spaghetti. My mother wasn’t a great cook and the meatballs felt leaden in my stomach. I couldn’t wait for dinner to be over so we could hide in my room again. My mother asked Meg but asked her about her favorite film (Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid) her favorite record was (Revolver, which surprised me, since I always thought it was Sergeant Pepper) and her favorite teacher in school, which Meg said was Mr. Kress our math teacher which I also knew was a lie since Meg and I hated all our teachers. After dessert Meg and I helped clear the plates. Suddenly the kitchen door burst open. My grandfather, swaying as if he was standing on a rocky boat, stood there in his blue pajamas my mother had bought for him.

“Now father, it’s time for you to go to bed,” my mother said, placing a hand on his shoulder. He pushed my mother away so hard that she almost fell against the stove. Then he turned to Meg.

“Jap Alert!” he suddenly screamed. “Jap Alert!

He grabbed Meg’s arm, shrieking in a high piercing voice. My mother and I were too stunned to move. Then, with still the almost superhuman strength he threw his arms around Meg and pushed her onto the floor.

“Grandpa, stop, stop!” I screamed

Meg’s eyes were wide with terror. “Help me,” she pleaded. My grandfather’s hands clutched Meg’s wrists and she writhed back and forced to escape his grip. I started pounding at his back with my fists but he wouldn’t let go of Meg.

“Father, you’re not in the war anymore, you’re here at home in New York,” my mother pleaded. She tried to pull him off Meg but he shoved her aside. His hands were now clasped across Meg’s throat. Her face was white and although her mouth was open, she was too terrified to scream.

“Leah, help me,” my mother shouted. I tried to take hold of my grandfather but his hands were still wrapped around Meg’s throat. My mother grabbed a cast iron pan from the stove and hit it against my grandfather’s head. He shouted out in surprise and finally released his hold on Meg. With a sharp cry he fell unconscious on the floor.

The rest of the night was a blur. My mother got hold of my father who came home immediately. Two ambulances were called, one for Meg and one for my grandfather. I was too much in shock to do anything but sit on my bed, my arms wrapped around my knees, my head down, rocking back and forth.

Hours later my father entered my bedroom and sat at the edge of my bed. The room was in darkness and he turned on my lamp. When I looked up at him, I could see that his face was streaked with tears.

“I’m very sorry,” he said. His nose ran as he cried and he wiped his face with his hands. “What Grandpa did was appalling. But he didn’t realize what he was doing. He never would have hurt your friend if he wasn’t so sick. You have to understand Grandpa saw terrible, terrible things in the South Pacific. Now, with the dementia, it’s as if every day he’s back there again. That’s why he attacked Meg. He thought she was the enemy.”

“He nearly killed her!” I shouted.

“I know. I know.” My father’s voice was muffled. I wouldn’t look at him when he left the room.

I wanted to hate my grandfather, but I couldn’t. Would Meg ever forgive me?

My grandfather, who did not even suffer a concussion, was sent to a home for Alzheimer’s patients. Meg’s mother flew back from Hong Kong and when my mother telephoned her to check on Meg, Mrs. Chen hung up the phone. Meg was absent from school for two weeks. No one would tell me what happened to her. The headmistress said it was a confidential matter. I even waited outside her building every day but didn’t see anyone in her family. When I asked the doorman what had happened to the Chens, he told me they were away.

“Away where?” I asked.

“There’s the maid,” he said, pointing to an elderly woman who was leaving the elevator. “Ask her.”

But when I approached their housekeeper, her eyes widened in terror the same way Meg had stared at my grandfather. She shook her finger at me and to my surprise, actually ran out of the lobby and down the block, as if I too was about to harm her.

Meg eventually returned to school, but only to gather her belongings from her locker. Our homeroom teacher had announced her departure in class, explaining that Meg’s family was relocating to Hong Kong. Meg wouldn’t look at me in class. When I saw her head to the rest room, I followed. I waited outside her stall and when Meg opened the door, she had a bunch of toilet paper in her hand and her eyes were swollen from crying.

“Meg, I’m so sorry,” I told her.

“I don’t want to go to Hong Kong. And it’s all your fault. My mom says it’s not safe for Amy and me to be in America.”

“Please,” I pleaded. “My grandfather is sick. He didn’t mean to hurt you.”

“He did hurt me! I’ve never been so terrified in my life! Do you know in the hospital they made me see a shrink who kept telling me that it wasn’t my fault? Of course, I know it wasn’t my fault. And now I have to leave.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said again. “Please can we be friends?”

For a moment I thought Meg was walking toward me to embrace me in forgiveness. Instead, she pushed me away with both hands that I nearly hit my head against the wall.

“No. Never. Paul is dead.”

She left the restroom and walked into the crowded hallway. I dried my face with a paper towel. From the classroom window, I watched a black car stop at the school entrance and Meg opening the door. The car sped down East End Avenue. I would never see her again. Meg wasn’t even included in the school yearbook.

The following year I was enrolled in a new school that was co-ed. I missed Meg, even though I had a new friend, Summer, whose parents were hippies and followed The Grateful Dead across the country. When I mentioned to Summer I liked The Beatles, she said they were the past and The Dead were the future.

Meg became a distant memory, except when I visited my grandfather in his nursing home. Every time I saw him, the image of his hands wrapped around Meg’s throat came back so clearly. But drugs rendered him a zombie for the final years of his life. When he died, there was no one at the funeral except my parents and my brother: all of our other relatives and my grandfather’s friends had passed away.

When I graduated high school, I chose to attend college in California. I wanted a change from New York and a break from my parents. After graduating, I moved to San Francisco and worked as an editor in a textbook publishing company. One December night I was proofreading a history book for sixth graders when I received a phone call from my brother, who was still living in New York City.

“John is dead,” he told me.

“Who?” I asked,

“John Lennon is dead,”

“No, Paul is dead,” I said automatically. I didn’t even realize what I was saying. My brother told me to turn on the news. Immediately I saw the grieving crowds outside The Dakota, the fans singing “Give Peace A Chance.”. I sat on my sofa and watched and when I started sobbing, I knew I wasn’t just mourning John Lennon. I missed Meg. I wanted her to be with me, that night of December 8th, 1980, comforting me about John’s senseless death.

That night, after I turned off the television, I lit a candle in remembrance of John. The candle also was a remembrance of my friendship with Meg. “Wherever you are, Meg,” I said in the stillness of my room. “I want you to know this candle I lit is also for you.”

I still had my old record player and my Beatles LP collection. I found Sergeant Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band and placed the needle on the track for “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Although I played the song repeatedly, no secret messages were revealed. All I heard was John’s lyrics of a place in Liverpool long abandoned but never forgotten.