My field is highly competitive, and up until a few weeks ago I wouldn’t have doled out any information. Information can be dangerous. Designing war machines often means knowing when to keep your trap shut. I’m taking this chance now for reasons I’m still working through. Perhaps this document will help me with that.

#

A Little About Me:

#

I’m 56 years old, and I’ve built robots my entire life.

I graduated top of my class from a prestigious engineering school at Tsinghua University, China. After graduating, legendary robotics developer Hao Luó poached me into his program and became my mentor. The program sought to advance the integration of autonomous and semi-autonomous war machines into the various branches of the Chinese military.

Battle Robots.

I’m not Chinese, but I speak okay-ish Mandarin. They hired 7 other individuals that year, all brilliant young Chinese men (and one very intense Korean woman). I didn’t like any of them– too timid as thinkers– their ideas too dependent on prior robotics theory.

Mr. Luó echoed this sentiment when he obtained my full security clearance after 6 months in the program, sending a memo to his superior, a General named Jia Xiáo:

“Most prospects take a turgid approach and recycle obsolete concepts, but this young man constantly questions everything from the ground up.”

I nearly fainted when I read that memo, but within 18 months I rose to become a division leader. Coincidentally, the intense Korean woman became my wife, at least for a time.

#

Now that we’re more acquainted, here are my three core principles:

#

Rule 1. Air Beats Land

#

This should be self-evident for the same reason cats seek high places when they hunt and eagles have no natural predators. It’s easier for a combatant to win a fight if they’re above their opponent. It also grants another dimension of mobility.

I’ve tested flying units against land units countless times. Really, countless times. Even the most nimble, spider-legged land robots get turned around against flyers.

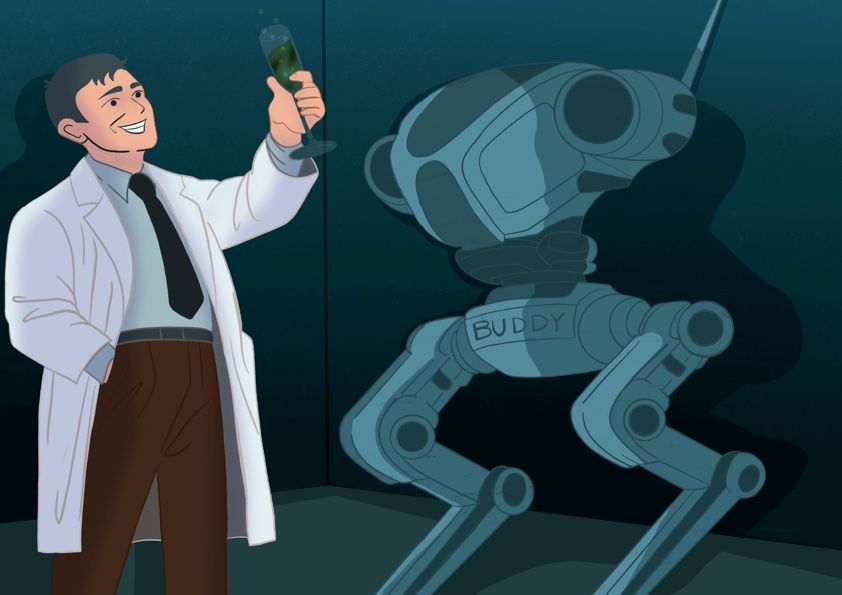

When I became a division team leader, we set to work trying to create a perfect flying unit. I named him Buddy. Been working on him ever since, alright. This task takes dedication. The real kind. The Korean woman, (my now ex-wife) dropped out of the program in her early 30’s. She told me her priorities shifted. I did not allow this to affect my work.

#

Rule 2. Heavy Metal Is Worth The Cost

#

Or in other words: powerful cannons are superior to the toughest armor plating.

Three years back, a rival division within the program wanted to test their land unit, called Shèng Jiǎchóng, which translates roughly to “Scarab.” They wanted to test it against my team’s unit, Buddy, and it fell on me to organize everything.

First thing I did was request my boss, Mr. Luó, to obtain extra funding for a chromium-molybdenum alloy, and then have it coated with tungsten-chromium through LMD (laser melting deposition). I coined a term for this material: “moon metal.” The cost was, shall we say, not wallet-friendly.

“I think I see your aim,” Luó told me, “but once you start using the heavy stuff, it tends to make little difference which alloy combination you choose.”

“I beg to differ,” I told him, “Grant me $15 million for the refining and encasement. I’ll prove it to you.”

My hotshot persona became a bit of a talking point after this, but Luó seemed intrigued.

Not he, nor anyone else, realized Scarab’s mighty armor plates were his biggest weakness. His team coated the armor in Rosler-M7. This additive hardens alloys into a diamond-like husk but possesses an unfortunate downside: anything coated in the stuff cracks apart like fortune cookies when impacted by moon metal.

And, naturally, Buddy’s primary weapon is a prototype cannon developed specifically to fire .50 caliber moon metal shells.

A month later, we finished assembling these shells, popped them into Buddy’s cannons, and told the Scarab team to meet Buddy at Bulagan Hural, Gobi Desert. Not exactly a picnic spot, but a nice venue for blowing up inferior robots.

The night before this confrontation, I conducted one final checkup on my mean machine. My wristwatch read 2:37 AM when I stopped by the hangar. The place was pitch black except the four large work lights set up around Buddy. He was covered in a special nylon tarp to keep him concealed which, though I understood the purpose, I always took as a personal slight.

I removed the nylon covering, and there he sat, all powered down. Standby mode. I put my hand on his smooth chassis. It was cold. My hand was warm, and I could feel heat transfer.

Then I recognized something within me. What an anomalous thing. A kind of wish for telepathy– to convey my hopes and knowledge to him and, likewise, hear his thoughts and questions for me. I did want it. Of course, this wish could not be fulfilled, no. I remember feeling an odd sadness. I put the tarp back on the unit. I left.

The next day, the battle robots met in the desert, and each division team monitored the test from miles off. Hao Luó also attended. Scarab started off his attack in standard rush-and-retreat, rolling up on his big dumb treads, making tactical blitzes followed by feigned withdrawals. Scarab’s main weapon consisted of an array of heat-seeking rockets. Buddy evaded them without issue. Scarab also tried firing his secondary chaingun but couldn’t move close enough.

“I’m seeing a lot of dancing and posturing,” Luó said, “but where’s that extra money gone? It’s not in Buddy’s back pocket, is it?”

“Patience, sir. Buddy’s just getting a read on him.”

“Getting a read on him, huh? Is he wearing glasses made of this ‘moon metal’ you keep going on about?”

Buddy zoomed and swooped around on his four mini-jets, each attached at different points on his chassis. A true demon drone. He stayed patient, bided his time, scanning and analyzing for the right moment.

His predictive software began telling him that opponent’s strategy was flawed. While Scarab’s meant to keep Buddy moving backwards by blitzing him, the repetitive nature of his attacks provided an opportunity. Buddy recognized each time Scarab fired off his rockets, he remained stationary a moment too long, stuck on the ground like a fat beetle.

Scarab rushed in again, lurching out from behind a hill. Pathetic. The second he fired his rockets, Buddy shot off a string of flares and swerved straight up. The flares drew the heat-seekers away, so once Buddy reached a steep angle, he fired a 4-shot blast from his cannon. It all happened in an instant.

When the shells hit Scarab, their moon metal alloy reacted with the Rosler-M7, shattering the entire outer layer of his armor plates. Poor dumb Scarab scrambled away like a cockroach, his carapace gone. We spared the rival team his destruction and further embarrassment. Hao Luó smiled at me.

#

Rule 3. Search-and-Destroy Software Is King

#

Notice I didn’t just say “software,” but rather “search-and-destroy software.” This is key. A lot of war machine engineers think they need everything– self-modulating cooling systems, predictive game theory algorithms, programs to distinguish bicycles from mopeds.

That is all pure nonsense. Your unit needs to be able to do one thing: target acquisition and termination. I programmed Buddy’s search-and-destroy software. It does what it’s supposed to: find the target, shoot the target, and it’s called MMYM (“Meow Meow, Yummy Mouse”).

Hao Luó asked me why I named the software that.

“I owned a cat once,” I told him, “My ex-wife recommended I get one. She’d wanted different things than I did, but after we split we…remained amicable. So I bought the cat. Only pet I ever had, except for Buddy, of course, but he’s more than just a pet. He’s like a son. You know this.”

“Yes.”

“I…also named the cat Buddy,” I said, “He used to prowl around the corners of my fireplace, spotting mice that came in from under the bricks, searching for crumbs. I watched him chase those mice and bat them around. Used to watch him a lot, even talk to him.”

“Alright.”

“He brought me one of the mice as a gift once– sort of laid it outside my bedroom door.”

“So what happened to the cat?” he asked.

“Don’t know. That was the last time I saw it. Just sort of…left me the dead mouse and took off.”

“Oh.”

“Was that what you came in here to talk about?”

“No. I think we’ve got some work,” Luó said, “The PLA has gotten in touch. A mission for Buddy…”

It turned out the PLA Airforce asked the program to find a band of smugglers operating on the Kyrgyzstan/China border in an area called Diemu Jiayi Luobaxi. The middle of nowhere. Apparently a group of about eight guys kept bringing crates of heroin into China through an elaborate mountain trail system.

The smugglers slept in a concrete bunker on the Kyrgyzstan side. Chinese reconnaissance obtained facial scans of two of the men. We fed the scans to Buddy and sent him over the border.

There wasn’t much for him to see– a handful of shacks and a few crops on stepped hills. But after about 40 minutes, Buddy spotted smoke billowing up from a camp. He deployed a tiny (but expensive) mini-drone to fly in for a closer look. The little fella barely made any noise at all, gliding when he neared the camp while his big brother hovered a mile away.

Buddy’s mini-drone then made a few silent passes and, sure enough, spotted one of the men from 100 feet up. They were unloading crates onto a little cart they used to pull around the mountrain trail. The mini-drone instantly relayed the face-ident scan back to Buddy. Then Buddy flew in and obliterated the whole place.

I never felt prouder than I did that day, never felt prouder. Successful operations and tests like these eventually led to a big contract from the Chinese military. They ordered an array of Buddy’s to be built and selected me to oversee production. All the hours I put in. Those strange times I wondered if I’d misspent my life raising the best battle robot possible.

The next day, I saw my ex-wife at a coffee shop we both frequented. Don’t ask me why, but I felt compelled to show her a copy of the military contract. She seemed a little distracted.

“Look, I just have to show you something,” I said.

“Alright, but can you make it quick, please? I gotta pick up my kids…”

“Look at this. You see that?”

“Oh…Okay, nice. Congrats,” she said.

“You see? Isn’t that something?”

“Yep. That is indeed something,” she said, nonchalant.

She left to pick up her kids. I felt a little foolish, but perhaps she just wanted to downplay my achievement. Perhaps she felt envious or resentful and thus placated me. Or maybe she really didn’t give a fuck at all.

Regardless, I chose to buy a bottle of champagne and visit Buddy in the hangar that night. Again, when I showed up, I found myself alone in the dark.

“Well, Buddy, we did it. Me and you. You and I. You’re the best thing in my life.”

After I took the tarp covering off him, I opened the champagne and poured some into a paper cup. I raised it up and looked at Buddy, the battle robot. I nodded my head, expecting to feel that resounding pride from the day before.

Instead, looking at that sleek, menacing chassis, a strange thought came into my head: having worked on Buddy for so long, he would certainly be of drinking age. Yet he could not raise his own paper cup in celebration. Then I thought of my ex-wife’s kids, and how the oldest was 21.

“Here’s to you, Buddy. Here’s to you.”