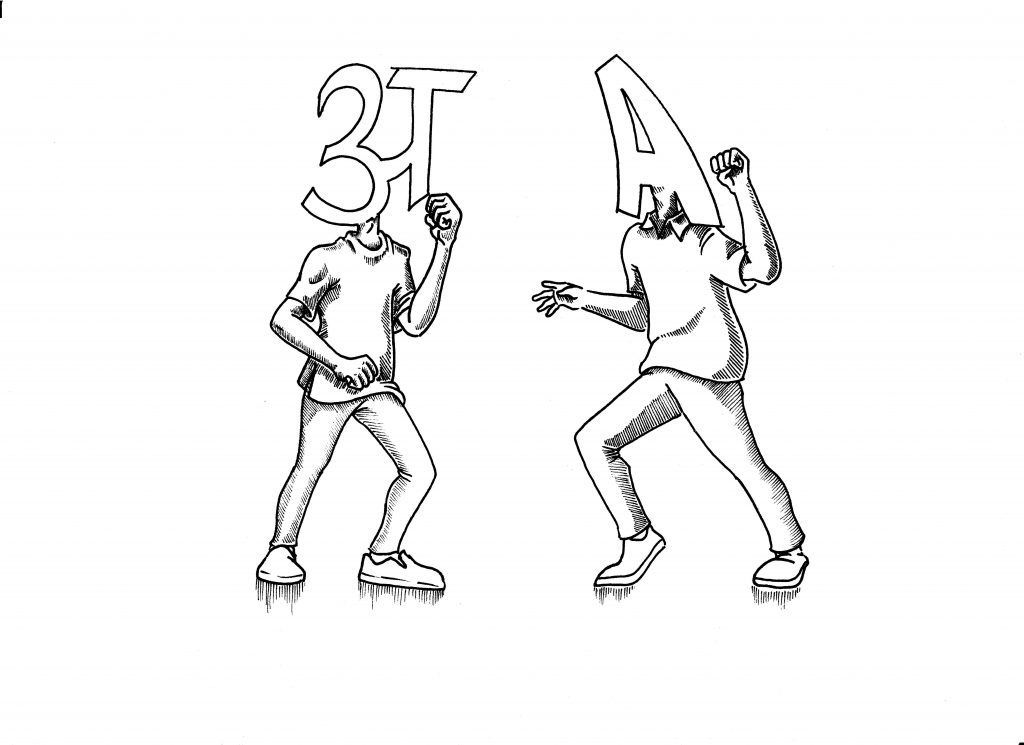

Secularism In The Midst Of UrbanisationRead More »

Interested in non-clickbait content? Become a member today.

You'll get access to:

- All content

- Comic Books

- Personalized cartoons

- Member credits in our videos and much more!

Already a member? Log In

Illustration by Allen B Thangkhiew

Secularism In The Midst Of UrbanisationRead More »

Already a member? Log In