Paul walked through the neighborhood of small, wood frame houses in the early morning light. Ahead of him, rising above the roofs of the neighborhood on a metal pole, was a life–sized cross with a bronze cast of the body of Jesus. Often, on cloudy, dark mornings, a shaft of golden sunlight pierced the low clouds and shone directly on the body of Jesus. Paul had seen it many times.

He turned a corner and came into sight of Christ the Redeemer Church. Made of cheerless burgundy brick, it squatted there among the houses surrounding it, without a steeple stretching into the sky like the other two Catholic churches in town, or wide cement steps rising to a great landing.

As he neared it, he cut through the yard between the church and the parish house where Father lived, and through a side door he entered the sacristy. It was empty. It was forty–five minutes until the 8:00 am Monday morning Mass. He was one of two sixth–grade altar boys assigned to assist Father.

From a wide drawer he removed a black pullover robe called a cassock. He unfolded it, poked his head through the opening, and let it fall around him. It extended to the tops of his black tennis shoes. They had been instructed to wear dark colored shoes. It was thought that white tennis shoes detracted from the solemnity of the Mass. Some altar boys wore white tennis shoe anyway. It was something Paul couldn’t quite understand.

The surplice, a loose white frock that went over the Cossack, he would not put on till just before mass. In front of the preparation table were two small glass containers, called thuribles. From the large cabinet behind the table, he took a half–full bottle of wine, worked the cork off it, and filled one of the containers. The unpleasant aroma of the wine filled the small space. He returned the wine bottle to the cabinet, and filled the other container with tap water. He placed them on a small tray and walked onto and across the altar. When he got to the middle of the altar, he faced the tabernacle and genuflected. He continued on to the side of the alter and placed the tray on a small table and walked back to the sacristy.

The church’s custodian, Gus Lindquist, came through the sacristy door. He was a tall, lean man. His arms were muscular and wreathed by thick veins. Black hair still grew on the sides and back of his head, but the top of it was bare.

He nodded to Paul. “Who’s your partner today?”

“Craig Bernakie.”

“Bernakie? We’ll be lucky if he shows up.”

Paul thought so too. Bernakie was one of those who wore white tennis shoes. In summer, with school out, many of the altar boys found it hard to make it to weekday masses.

“What about Father Rick?”

“I haven’t seen him.”

Gus went to the church’s fuse box, opened it and started flipping switches. With each snap light burst over a section of the church. It was a half hour before Mass and people would start entering the church soon. Gus went out the sacristy door.

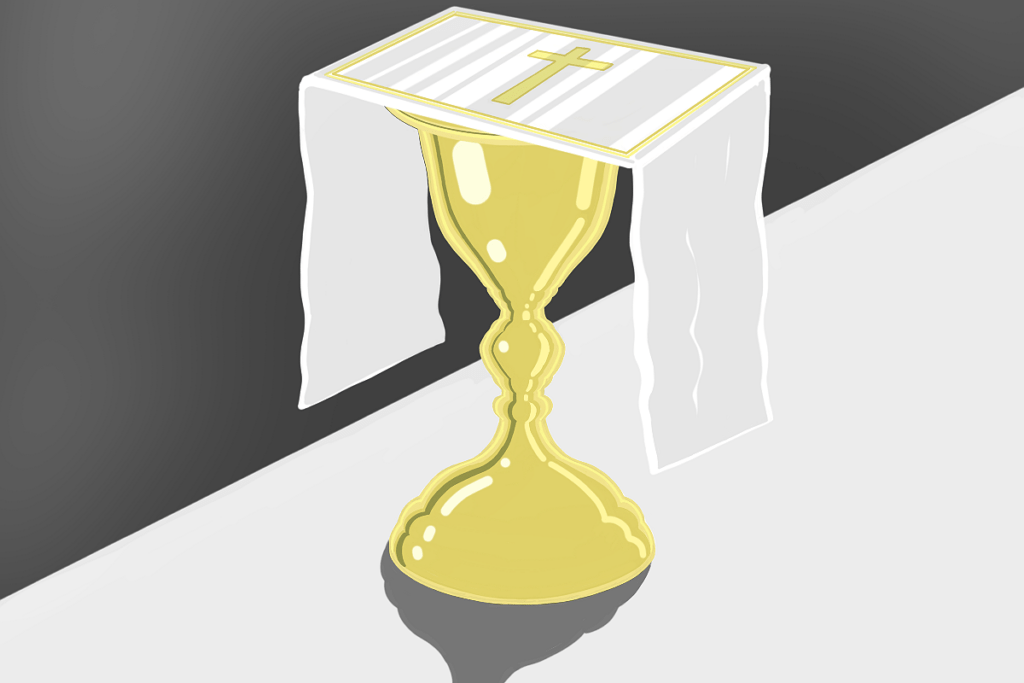

A gold chalice was in the cabinet. Paul took it out and placed it on the preparation table. Five items were required to prepare the chalice for Mass. They all had formal names and he had learned those names a long time ago. He placed a small cloth called a purificator sideways over the chalice, and over that, and onto the chalice, a gold plate, called a paten, with a large host on it. A pall, which was a thick square cloth, he neatly arranged so that it spread evenly over and around the chalice. The color of the pall could change depending on the church calendar. Since this was considered ordinary time, the color was green. Finally, he took a small square of heavy cloth, called a burse, with an opening on one edge, and inserted a folded white cloth, called a corporeal, into it and placed it on top of the pall. Now it was ready.

He opened the sacristy door and looked outside. A light was on in the kitchen of the parish house. He was able to see a good distance in front of and in the back of the church. He didn’t see Bernakie.

He could serve the Mass himself. He had done it before. It took a bit of running, and some patience from Father, but it could be done.

He went back inside and peeked out the opening to the altar at the pews. Three elderly women were seated, far apart from each other. Most of the attendees, he knew, were widows. Gus Lindquist had told him so.

“They’re all widows. Widows praying for their dead husbands, or themselves. It’s the highlight of their day.”

Father should be here by now, getting into his green vestments. Perhaps he was sick again. At Sunday Mass the day before, which Paul had also served, Father had been sweating terribly, sweat rolling down his forehead, and shaking so badly that Paul was afraid he would drop the host when he served communion. Unfortunately, Father was often like this. It was part of his illness, Paul assumed. When he asked his parents what was wrong with Father, they told him Father had malaria. He had believed this, but lately some of the altar boys, Bernakie and others, claimed it was something else.

More people came into the church. More widows, and a middle–aged man in a business suit near the front, kneeling, his eyes closed tightly, his hands pressed together in front of his face.

The hour was coming close to 8:00 am. It was five minutes before the Mass would start. Paul was on the verge of lighting the candles but was uncertain if he should wait till Father showed up. Gus came into the sacristy and looked around.

“Is Father here yet?”

Paul shook his head.

“It’s time to ring the bells. I’ll ring ‘em long and loud.”

Gus went through a door in the vestibule to the bell tower. Paul could see him through the door. A cable like rope hung from the bell. Gus grabbed the rope with both hands and pulled down, his body straining. When the rope came down, he grabbed it further up. Slowly, the rope went upward and pulled him a foot off the ground. Paul could hear the creaking and rocking of the bell on its carriage. Gus came back down and touched the floor with his feet and the first cautious ring came. The bell pulled the rope back up and now he was two feet off the floor. When he came back down the bell rang more loudly. Soon the bell’s ringing reverberated throughout the neighborhood.

After a few minutes, Gus let the rope go. As the ringing faded, Paul looked out the door again to Father’s house. As before, only a kitchen light was on. It was nearly 8:00 am. He shook his head. The only thing to do now was wait. It was sometimes ten or fifteen minutes before Father showed up. But he always showed up.

He looked at the congregation again. A dozen people sat in the pews. Most of them had been through late Masses with Father. They sat quietly.

Paul put the surplice over his head and over the black cassock. He went onto the alter and lit the three candles. His preparations were now complete.

He stood quietly in the sacristy looking at the altar. The flames of the candles were unmoving. A statue of Jesus on the cross was mounted behind and above the altar, overlooking it. It had replaced an older statue a few months before. Father had found it somewhere and had it mounted. Some parishioners, including his parents, had grumbled.

At dinner one night his father shook his head. “What kind of statue is that to put in a church? Where is the triumph, the victory?” He held a forkful of roast beef and mashed potatoes in front of his mouth. “It’s–it’s just upsetting.”

Unlike some statues of Jesus on the cross that were almost regal, that made suffering seem almost sterile, this one showed Jesus’ head slung forward with his eyebrows drooped and slanted, as if he was about to weep. His eyes were black and undefined.

A few weeks before, after a Friday morning Mass, Father had come out onto the alter while Paul was extinguishing the candles. From the darkened alter he stood looking at the cross. As Paul came near him he said, “Look at that Paul.” Paul followed his gaze to the cross. “Look into the eyes. Into the endless depths of suffering.” He turned to Paul. “Do you see it?”

Father had a rich, sonorous, baritone voice. In the two years he had been the parish’s priest, people often remarked on it. They talked about how pleasant it was to hear father preach a sermon. But now Paul could hear cracks in his voice.

Paul nodded his head, even though he didn’t fully understand.

At fifteen minutes after 8:00 am, a woman came in the sacristy. She was father’s housekeeper and cook. She was one of the widows Gus referred to, at Mass every morning. She wore a scarf pulled tightly over her head and tied in a knot behind. Paul remembered how she beat her chest at the saying of the Agnus Dei during the breaking of the host: “Lamb of God, you who take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Lamb of God…”

The woman approached Gus.

“Father Rick isn’t up yet. I called to him up the stairs a few times but he hasn’t answered.”

Gus stood unmoving, his mouth tight, his arms folded in front of him.

“Can you go see about him?”

When he spoke, his voice was agitated. “Hell no, I can’t see about him. I’m not in charge of him, thank God.”

“Just go look. That’s all.” Gus shook his head.

The woman turned toward Paul. “Will you go check? Just knock on the bedroom door and see if he answers.”

Gus cut in. “You can’t put that on the boy! It’s his job even less than mine.”

The woman ignored Gus. “Will you?”

It was some seconds before Paul could answer. “I guess I could go knock on the door.” He saw Gus shaking his head. “I guess I could do that.”

“Walk up the stairs. It’s the first door on the left.”

He went out the sacristy door and took the short sidewalk to the back entrance of the parish house. He opened the wooden door and entered the kitchen and looked around. On the kitchen table was a plate with two pieces of buttered toast and two fried eggs speckled with pepper. He had not been in Father’s house ever. It looked a great deal like his own.

The house was quiet and a stairway was off to his right. He walked toward it and started climbing, his steps slow. The top of the hallway was dark and muddled. The door was there on the left, open a half foot. He walked to it and stood in front of it, swallowed, and knocked.

There was no answer. He called quietly. “Father? Are you there?”

He heard nothing. Slowly he opened the door and stepped into the doorway. The bedroom was as dark as the hallway, but he could see a tangled bundle of blankets on the bed and Father’s form among them. He spoke hesitantly. “Father, it’s time for Mass.”

The figure on the bed only groaned and turned to one side. Without warning, sorrow gripped Paul, a sorrow so fierce that he thought he could not stand it.

He closed the door and walked down the stairway and out of the house. When he entered the sacristy, Gus and the pious woman were waiting.

“Well?” Gus said.

Paul could only shake his head, holding his face away from the two.

“Somebody should do something about it,” the pious woman said. “Somebody should tell the bishop.”

“What makes you think he doesn’t know? He knows. You can’t keep stuff like that quiet.”

They saw Paul listening. Gus spoke to him. “Paul, you put everything away and clean up. I’ll tell the people there won’t be any Mass today.”

When he was done, Paul walked home through the neighborhood. He turned once to look at the cross on top of the church. He looked at it for a long minute, then turned and continued on home.