The Chechen never rode anywhere. He knew what he would face once he arrived in Afghanistan and he knew who he had to be, so he walked.

His grandfather saw the Turks when they came to his Armenian village in the shadow of Mt. Ararat in 1916. The Turks killed everyone and everything, raping and looting and laughing. They thought they had killed his grandfather too, but they hadn’t. Grandfather often wished they had. Grandfather told him that story many times. The Chechen lived elsewhere now but he never forgot and he never forgave. Russians were today’s Turks.

The Chechen was from Grozny, the large capital city of Chechnya which no longer exists. The damned Russians had destroyed it and killed its citizens, something the West never quite understood.

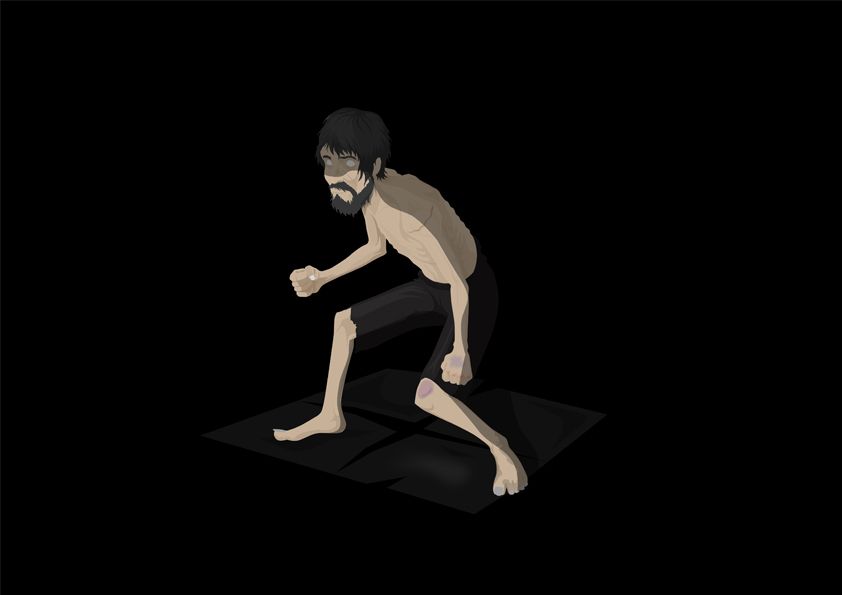

He never fit in. He was small, wiry, fast. He was scarred early. He played futbol with the bigger boys until they became too frightened of him to play anymore. He earned the best marks in school until his teachers became too frightened to teach him. He had one or two friends but the friendships never lasted. It’s hard to be close to someone you fear.

His mother was educated, a science teacher. He learned from her after the schools expelled him. He loved history and languages. By the time he was fifteen he could speak Chechen, Armenian, Georgian, Pashto and Russian.

He was conversational in Farsi and Dari as well, and he knew enough Arabic to get by. There were enclaves of those cultures in the great city Tbilisi where he now lived. He could mingle and shop and steal in any of them.

He knew Chechen history, regional history and tribal histories. He knew who hated whom and why. He knew the history of the communist party and he noticed when it departed from other accounts of the same events. He devoured knowledge, he retained it and he used it as a tool.

He was a Soviet Army “captured volunteer” at the age of 16. He lied to every question the sergeants asked him. In the middle of the Afghan War the army needed every warm body it could find. He excelled in basic and advanced infantry training. He learned how to kill in the silent ways.

The Chechen was violent when violence was called for. The rest of the time most people left him alone. He made his first close friend, Dagga, during training. Dagga got in under his wire mostly because he knew the value of silence. Dagga was a Georgian, another “Black Ass” Soviet. Dagga was strong, but not like him; violent, but not like him; angry, but not like him.

The two of them finished training and were assigned to a unit of transport troops. “Hey, we’ve got a couple new Black Asses” a sergeant yelled to his friends.

The sergeant approached him. “Can you read, baby-faced Black Ass?” Silence, no answer to the insult. The sergeant took off his garrison cap, rolled it up and slapped him hard across his face, the cap star raising an angry welt.

“I said can you read, Black Ass!” Nothing.

“Fuck your mother but I hate all Black Asses.” He turned to Dagga and slapped him across the face. At the end of the slap his arm stopped moving without him willing it. The Chechen had it in his right hand and the sergeant was frozen. They stood eye-to-eye, right hand-to-right hand, for a moment. Then the Chechen pushed the front of the sergeant’s right bicep with his left hand and jerked back with his right hand, tearing the sergeant’s elbow out of its joint. Then he stepped back.

The sergeant screamed and tried to hold on to his right arm, but he couldn’t find a spot that didn’t shoot agony up into his shoulder and down to his hand, so he let it hang, and he cried. Someone called the police. They surrounded him and beat him senseless but he didn’t fight back. They threw him in the back of a small truck and took him to the punishment cells.

The punishment cell was too small to lay down in and too low to stand up in, like a cement coffin. There was no window, no light except what filtered in from the corridor, no water and only a hole in the floor for a toilet.

The guards came by once a day and threw in some food, aiming for the cess hole. If he could catch some or scrape it off the filthy floor, then he could eat. If not, he starved. A bucket man came by twice a day and poured dirty water through the food slot. He learned to catch some of it with his tattered shirt. That way it would last a little longer while he sucked it out of the cloth.

At the end of a week, he knew he was going to die. The beating had raised large sores that had become infected and completely changed the way he looked. The places where his teeth had been shattered became infected as well, giving his mouth a grotesque look and giving his tongue no end of painful gaps to explore.

One day things changed. Two guards appeared and rousted him out into the corridor and pushed him along into some kind of administrative area and sat him down on a hard bench. Every hunched-over step was agony, every movement an exquisite silent torture.

A sergeant came in and stared at him, drew his knife. “You crippled my friend. If I kill you right now no one will say a word. I‘ll say it was self-defense and you won’t be able to say anything, you’ll be dead.” He knew the sergeant was right and there was nothing he could do.

A transport troops lieutenant came in and began to ask questions. “Your name? Pay number? Date of birth? Do you understand why you’re here?” Nod. “Do you understand that under military law you have no rights?” Nod. “Do you understand that you have committed a crime for which the punishment can be death?” Nod. “This is your confession. Sign it right there.” He signed.

The sergeant and lieutenant left him with just one guard. Everyone understood the situation. There would be no mercy. Examples occasionally had to be made.

A major came in. Not a transport major. The Chechen recognized his blue KGB shoulder boards. He brought his own folding chair and sat down next to him.

“Not good, comrade. Not good at all. You were here for two days and you cost the Soviet Army a sergeant. Not good.” It wasn’t a question and he didn’t answer.

“Corporal, bring in some water” the major shouted into the hall. A corporal entered with a bucket of water, a ladle and a towel. “Here”, the major said, “take a drink and wash the crust off your face.”

“Thank you, comrade major”, he croaked. “Was that really my voice?” he wondered. “Have I always sounded like that?”

“So you’re Viktor Borisovich Markovyan. Do I have that right?”

“Yes, comrade major.”

“You’re a fighter, I can see that, but it looks like you lost your last one.”

“It wasn’t a fight, comrade major, it was a beating. You don’t win or lose a beating, you just get beaten.” The major wasn’t listening.

He glanced at the folder he had brought. “Do you really speak Pashto?” “Yes, comrade major.” “Who taught you?” “My mother did.”

The major launched into quick Pashto, laced with idioms and filled with errors, finishing with “And was your mother the village whore who picked up some Pashto from passing truck drivers?”

Viktor replied in perfect Pashto, “Comrade major, that is the worst attempt at Pashto I have ever heard.” The major responded in his own perfect Pashto “Thank you, Viktor. At least you know the difference.”

The major asked “Have you eaten anything?” “Only the shit soup they pour on you in here.” The major called out again “Corporal, find this man some soup and bread, some real soup, with vegetables and salt.”

The corporal came back with a dented metal bowl and a wooden spoon, then he brought in a bucket of hot cabbage soup and ladled it into the bowl. He offered a piece of flat bread. “Go ahead, eat” said the major. “We have much to talk about.”

The Chechen spooned up the soup, spilling it on himself, wiping up the spills on his shirt with the flat bread. The major finally said “There’s a cot over there. Get some sleep. I will send you some clothes. Clean up. I’m going to send you to a school.”

Chapter 2

He walked for hundreds of miles. He blended well and no one asked him any questions at first.

His mission was to infiltrate the mujaheddin, the Afghan alliance that had stalled the advance of the Soviet Army and made them look like inept fools in the eyes of the world. The same mujaheddin that was giving the Soviet Union its own Vietnam, its own military quagmire.

He had been trained by ingenious intelligence agents. They honed his skills, gave him new ones and made him a fighting man to be reckoned with. But not yet.

The Chechen began in Ashgabat, in southern Turkmenistan. Instead of a direct and much easier southeast route into Afghanistan he had walked south into Iran. It was easy, really. He was one of twenty million stateless souls on the road to nowhere, another lost man.

He walked the roads from Ashgabat to Mashhad, south along the A-01, crossing into Afghanistan west of Esiam. He learned to harvest the poppy fields where he was accepted as simply one of “us”. Poppy workers could always find work and no one asked any questions.

He became a wandering field worker except that he wasn’t wandering. He traveled east down the long green valley first to Herat, from Herat to the great city Kabul, from Kabul toward the center of Afghan resistance high in the Tora Bora mountains.

Along the way people began to notice him. “Hello brother. We met in the fields two months ago. Will you drink tea with us?” There were no friends yet. There couldn’t be. To confide was to die.

There was the occasional woman. To not take a woman was to not be a man, to not be a man was to be shunned. To be shunned was to be remembered.

Information moved ahead of him. It was a commodity, sold and passed along and sold again. “We saw that Chechen again.” When, where? “Here brother, take these coins and remember us next time.”

One or two workers were always friendlier than the rest. He understood and let those friendships grow. Soon they drifted away but others followed. One day, east of Kabul, “There is no more work this year, friend. Where are you going?” “East”, he replied.

“East is death, friend.” The Chechen had seen the Russian convoys as they passed him on the roads, blinding him with dust and grit, and he heard the jeers of the young Russian soldiers. He had seen the transport and attack planes, the damned MI-24 “Crocodile” attack helicopters, the scout planes.

How many Russian patrols had asked him for his documents? They questioned him harshly when they found that he was completely without papers. “I am a wanderer, master. What papers should I have? Who will give them to me?”

Twice he was beaten, submitting to the taunts and poundings of frustrated soldiers who couldn’t find their real enemies. He was an unlucky peasant, a convenient whipping boy for bored soldiers with too many dead friends.

Chapter 3

The great mountains were only a vague outline on the distant horizon. He found a spot to rest for the night. He took out some rice and tea and dried apricots, built a small fire, boiled some water, ate and waited for the men. They came at midnight.

One called out “Stranger, have you any food?”

“Yes, friend. Sit with me and be welcome. I am Abdul Wassaraf.” Two men walked slowly into the circle of firelight. One leaned down, added some wood to the fire, brushed himself off and sat down. The other stood nearby.

No one spoke until after tea. “I am Rashid, son of Rashid” said one. “We know of you but we do not know about you. You have traveled far and you have worked the poppies. Why are you here? We have no poppies and no work.” The stranger spoke without malice, with a curious interest as if watching an insect that he had never seen before.

“I have come to kill Russians” said the Georgian.

Rashid laughed. “Then you have come here to die, friend. We fear the Russians. We pay their officers tribute to leave our villages alone, to let our boys and our women live in peace. We trade with them for their tobacco and jams and guns. We do the jobs their soldiers hate. We sell them information and we give them people like you. You won’t be the first.”

“Then I am in the wrong place” said the Chechen. “I seek those who would drive the infidels from Afghanistan, punish them for inflicting their ways on Afghans and warn them not to do so to others. I do not seek those who would lie at their feet like dogs and lick the crumbs from their bowls.”

Rashid turned to the one in the shadows, said nothing to him, said to Abdul “You are not one of us. Why do you care about Afghan problems?”

Abdul replied “Because the Russians will use Afghanistan as their island in Central Asia, from there to devour Iran. I am a Kurd. My people wish to live in peace in their own nation. That will never happen if the Russians control Afghanistan. Besides…” and he let a small smile escape, “Is there a bad reason for killing Russians? More tea?”

The conversation continued quietly, in the way of the men of that region, sometimes banter, sometimes questions. Rashid asked “Do you bring anything but your short knife to this quest?” “No” answered the Chechen, “but it will be enough to start. I will take the things I need from the bodies of Russian soldiers.”

“Other things? What other things do you need? Guns? There are guns everywhere.”

“Maps” said Abdul, “codes, frequencies, call signs, routes, unit designations.”

Rashid leapt to his feet. “Spy! Traitor! What do you know of such things? Better we kill you now than go on.”

“Sit down, friend. I answered your questions truthfully. You didn’t ask the right ones.”

The third man moved in from the shadows where he had been standing. “I am Ahmad, son of Ahmad. What questions should we have asked you?”

“Peace, Ahmad. Sit with us. Perhaps you should have asked if I have killed Russians before. Or if I know how to use these other things I need. Or if I have ideas. You will kill more Russians with ideas than with your worn-out Kalishnikovs.”

“Well? Have you killed Russians?” Then, “Tell me your story and your ideas.”

Chapter 4

“The Russians came to Grozny to capture ‘recruits.’ I was one of them. I served in the Soviet Army for twenty months. I became a driver because I could drive the large trucks and fix them when they broke down.

“I spent ten months in a camp outside of Kabul, driving convoys into the mountains, always afraid of Afghan ambushes but always staying alive. My unit fought its way out of ambushes that should have killed us. Should have, but failed because the Afghans were brave but poorly led. I drove the command vehicle. I watched each ambush unfold even as I fought back.

After the last ambush our commander was arrested for incompetence. He had no excuse, he was incompetent and worse. As an officer, he was allowed to state his defense.

He was a typical Soviet officer. He blamed his men, especially his black ass drivers, for cooperating with the enemy by driving into the ambushes. He named me and four other drivers. We were to be arrested. Our commander was to be sent back to Russia.

The other four were arrested and shot for treason. Their only crime had been to follow orders and risk their lives for a fool of a commander. I hid.

A few days later the officer was to fly out of the country to safety, to the arms of his woman, to tell stories of his bravery to any fool who would listen while the bodies of the men who had followed him rotted in a single pit.

I knew he would be drunk on his last night. He called for a tray of food. I paid the native who was to serve him. I backed into his room carrying the large tray. He couldn’t see my face.

When I turned around I cut his throat with this short knife. He knew, in his last seconds he knew what had happened and who had done it. He tried to scream but only air and blood came out of the gash. He grabbed me and looked into my eyes and then he folded to the floor.

After that I changed into one of his uniforms and waited with his body until very late. I let myself out and I was gone for hours before anyone ever came for him. I made my way to Iran, thinking I could start a new life in a village that needed a mechanic, but that life was behind me now. After one season I decided to return to the front, this time fighting with the Afghans. Now I’m here and my past no longer matters. I will kill Russians until they kill me and that is all.