I wanted to write this anecdote at a café that I used to frequent. Its window wall was the most amiable screen to run a view of Dongdaemun, the eastern gate of the fortress wall which surrounded Old Seoul. I could not, as the café is gone now. All that hurly-burly of urban renewals and rent hikes in Seoul does not casually tolerate a small business to settle down but for a relatively short time. I am honestly awestruck that Dongdaemun has not been torn down yet, so that its site can be redeveloped into a more profitable type of real estate in fashion―a tollgate with some aesthetic hints of the Capitol from The Hunger Games, for instance. Dongdaemun no longer bears a practical function anyways; Seoul is not a walled city anymore.

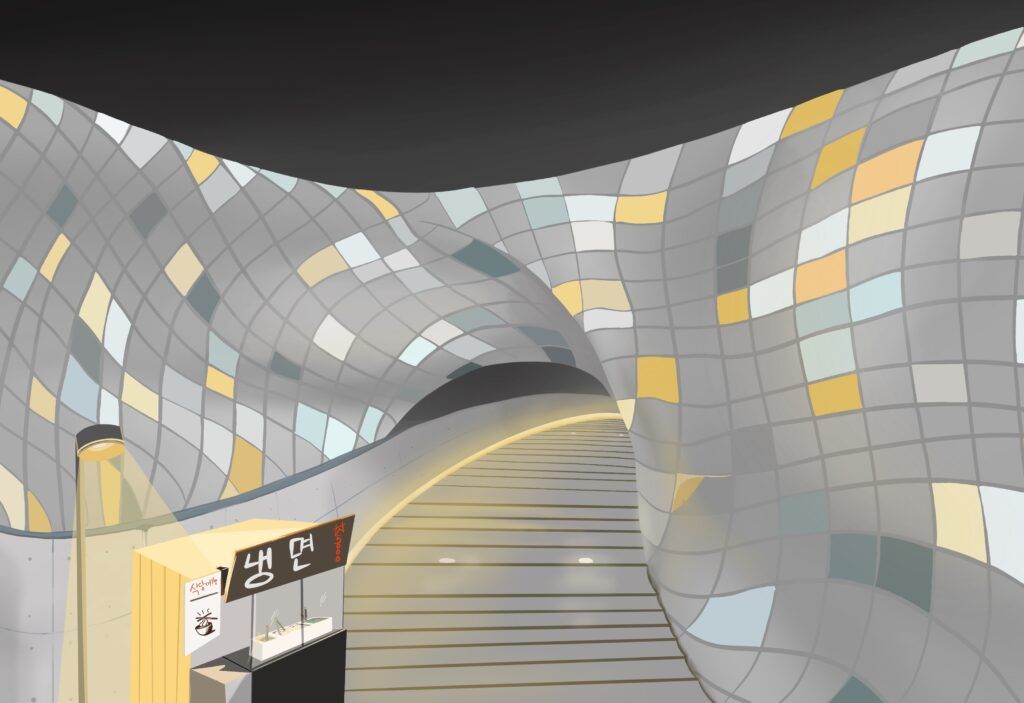

2023 marks the tenth anniversary of BTS. This I learned from a projection beamed onto the façade of Dongdaemun Design Plaza. DDP, a building complex that is obviously very close to Dongdaemun, has boasted Zaha Hadid’s neo-futuristic design from its heyday. The original visionary charm DDP held when it made an appearance in a somewhat cyberpunk music video of 2NE1, arguably the prototype of Blackpink that debuted in 2009, is nonetheless pretty much gone from the local perspective.

DDP still attracts plenty of foreign tourists though. In order to read what was written on the projection, I had to see through tourists from Malaysia, China, and Francophone Africa. Meanwhile, the words celebrating the anniversary of BTS were written in English. It was chosen to let the majority of people traveling here from abroad understand the message, presumably. After all, the language choice was proving itself to be fair with a multinational crowd of tourists taking pictures in front of DDP lit up in purple, the official color of BTS’ fandom.

The tourists would have certainly understood the celebratory message of the K-Pop capital. But now I wonder if tourists in Seoul understand that sometimes, ten years can feel like an eternity here. Whatever is in Seoul tends not to crumble away, but rather abruptly ceases to exist. There is a Korean saying that even rivers and mountains change in ten years, where “rivers and mountains” are used as a conventional synecdoche for the natural landscape and deemed to be everlasting in a relative sense. In reality, no one can see a mountain gradually decay or a river steadily dry at every moment. Later on, one suddenly finds that they no longer look the same or are even gone. Such changes cannot be measured in linear times; it takes discontinuous eternities to grasp them, albeit imperfectly.

As I write, I am unexpectedly reminded that DDP was built upon the debris of Dongdaemun Stadium, and Dongdaemun Stadium upon the remnants of the old fortress wall. The masons of the late fourteenth century who built the wall would have hardly thought of its stones eventually falling away, much less imagined something like a sports stadium or a neo-futuristic building complex to replace them.

Truly, Blackpink is “forever young” ―once they are not young, Blackpink will be no more.

*

The only visible Russophone community I know of in Seoul is situated right across the boulevard from DDP. Needless to say, it is in the vicinity of Dongdaemun as well. The municipality has named the place Central Asia Village, where many Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Russians, and Ukrainians can be spotted. Despite that Mongols in the area do not share the Eurasian lingua franca of the other ethnic groups, Mongolian places do blend in well in that they write out their signs with the Cyrillic script.

A Russian acquaintance of mine from Murmansk, now an expatriate in South Korea, once visited Central Asia Village. I have never been made privy to the personal reasons for his recent immigration. He lives alone in another city and had had not the faintest idea that such a place existed in Seoul before. The visit was an occasion for his long-awaited spoken dialogue in Russian, as he had not spoken a word of Russian in real life for weeks until he talked with servers at a Russian/Uzbek restaurant there. Strolling down the streets of the village after a satisfactory Soviet-style dinner, he murmured: Slav, Slav, and another Slav. He went on saying it, pointing at about a dozen people passing by.

After the draft orders in Russia, some Russians entering South Korea in a precipitous manner with tourist visas made it into the headlines a few times. They seem to be not as cheerful and enthusiastic about K-Pop as average foreign tourists in South Korea. This distinct type of Russians here and the village near Dongdaemun often make me think of Ivan Bunin. An heir of the Russian gentry, Bunin fled the Bolshevik Revolution and bounced around Constantinople, Belgrade, and Sofia. It was in Paris that he made the final edit of his autobiographical magnum opus, The Life of Arseniev. His aim in writing it, I believe, was to resurrect his home in the narrative method of the novel. Ironically, Bunin was the first White Russian émigré whose works were allowed to be published in post-revolutionary Russia, where Old Russia he knew had ceased to exist, swiftly swept away in the turmoil of the twentieth century.

I, who is not a White Russian émigré in Paris but a Korean in Seoul, that is, a man who is supposedly at his own home, nevertheless must ask―how does a person revivify one’s home, literarily at least, if there had never been anything or anywhere to call home at all but a flux?

*

Three renowned Hamheung cold noodle restaurants stand a block away from Central Asia Village; my favorite Hamheung cold noodle place that was also within walking distance from the Russian-speaking streets, however, was demolished several years ago along with other old buildings. Its name was Yetnaljib, which can be translated into English as Old House or Old Home. The construction of two high-rise buildings is already complete in the block where Yetnaljib was and more will follow, providing Seoul with hundreds of new apartments. I vividly remember the paintings hanging on Yetnaljib’s walls: a tiger in snow, winter mountains, a beauty in hanbok with flowers, and many more. Regretfully, I never had the chance to know what the hall on its second floor looked like, as there was an empty table on the first floor whenever I came to dine there.

Hamheung cold noodles is a cuisine from the northern part of the Korean peninsula adjoining China and Russia. Yetnaljib used to be a spot where old gentlemen from Hamgyoung Province, the northernmost area of Korea of which the provincial capital is Hamheung, would gather until comparatively recent times. They had fled North Korea before and after the Korean War that broke out in 1950. Most of them have passed away by now. These gentlemen never had the chance to return to Hamgyoung Province but frequented a place called Old Home. The home they knew in North Korea would be no more there and its mere emotional simulacrum here in South Korea was wiped away likewise.

Another White émigré and Russian writer, Vladimir Nabokov defined the Russian word toska as “a longing with nothing to long for.” Maybe I have never been longing for Yetnaljib or the café looking down Dongdaemun per se. Maybe, just maybe, I can find le mot juste for Seoul neither in English nor in Korean, and this lacking is not due to my linguistic deficiencies.

*

At Yetnaljib, I was first introduced to Hamheung cold noodles by my grandmother, whom her father had first brought to the now-gone restaurant in the 1950s. He worked as a wagoner on the outskirts of Seoul which would later be named Gangnam. All the wagoners along with their horses and wagons disappeared in only about seventy years, while Gangnam Style now feels like a hymn from antiquity.

Even though my grandmother’s father and I did not have the opportunity to talk with each other, it gives me a sense of awe that a man in Seoul whose life overlapped with that of mine for a few years had been a wagoner. It is a job unimaginable from my own experiences in Seoul.

My grandmother told me that once her father had carried a horse on his back. This happened at a time when there was no bridge over the Han River and people had to cross it on boats. The horse broke its forelegs when it jumped off the boat. Other people’s advice was to let the horse go. Even today, leg fractures are considered to be fatal for horses.

The wagoner from the now-gone Seoul thought otherwise. He chose to give the horse a piggyback. Technically speaking, its hindlegs were still stepping on the ground, but he did manage to bring the horse all the way home.

Such a story is a better fit for a mythical chronotope than a bustling modern city. The story feels surreal to me, and in ten years, Seoul as of now that I shall recount might likewise be perceived so. Thus I leave this record in case everything I know disappears from this city, although I wonder: what shall I be capable of bringing back home safely from the river of oblivion, in the city that has banished its horses with their wagoners?