I’m not so bad-looking. My dad says, “Honey, you’re certainly attractive enough for me,” which is sort of sweet but creepy and depressing. I mean, how much beauty can a girl embody at 17? I’ll tell you how much. You can be my best friend, Desi Wainwright, who’s stop the planets in their orbits beautiful. Not perky smiley face cheerleader plastic beautiful and not dark goth chiseled quoth the raven Nevermore beautiful. Just absolutely classic, elegant, enormous-eyed, wide-mouthed, fuck-all gorgeous. Picture Anne Hathaway and Audrey Hepburn, together, in one face, but perfecter. She’s been that way since we were in kindergarten, Desi, just a tiny, exquisite baby-plump version of herself. Five years old, sitting in a circle cutting construction paper into strips with little blunt plastic scissors, and I think, “Uh oh, this girl is gonna rule my life.”

So bless his little pointy head, my dad thinks — and this seems to be the consensus — I’m a nice-looking kid who doesn’t punch above her weight, beauty-wise, but when Desi comes over to our house, which she does two or three times a week for us to do homework, he — my dad — can’t suppress a sharp intake of breath as if her fantastic looks were a kick in the gut. When I go over to Desi’s house, her dad just says, “Hey, Andrea,” and I say “Hey, Mr. Wainwright,” and he says, with dad-humor inerrancy, “You girls working hard or hardly working?” My answer is always the same: “Little bit of both, I guess.” “Well,” he replies, totally unironically, “keep it up.” Keep it up, ha. I don’t raise a flutter in his heart or groin.

1

It’s that way everywhere. At the mall, where Desi and I hang out on Saturdays, trying on clothes we would never buy. At the movies or at a concert we’re allowed to attend. In the city, downtown, when we escape from our dismal suburb populated by blond moms in yoga clothes driving their SUVs around looking for radicchio. At school, five days a week. Men and boys tumble like aliens in a video game at the sight of her. We know what they’re thinking. Not just can I go out with you, hit a movie or thrift store, can I kiss you and fuck you, like all the regular things men and boys think, but can I take you far away, to dinner in Paris, can I spend a life with you, can I re-create all the transcendent moments of art and culture and history and lay them heroically at your feet. That kind of thing.

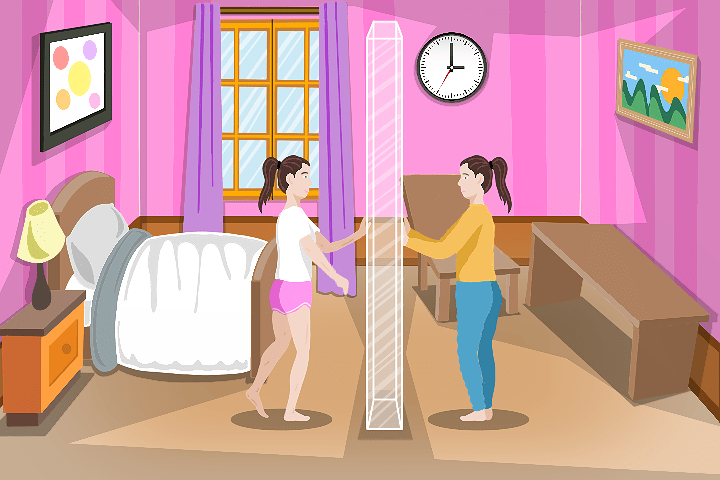

And I get it. Once when Desi was in my room, which is all pink and white and purple from when I was 12 and it seems like a waste of time and effort to redecorate, we took our clothes off and stood next to each other, looking at the long mirror that’s inside the closet door. I was a little embarrassed. She looked like a young goddess. I looked like a girl who might need a bra in years to come. She put her hand on my chest, which caused a stir in me, and said, “Andrea, you’re so sweet and pretty. I love how adorable you are.” So, I put a hand on one of her otherworldly breasts, which also caused a stir in me, and said, “Desi, there are absolutely no words for how beautiful you are. I love you too.” Which is not the same thing she said.

Truth is, I wanted to touch every square inch of her skin and then kiss every place I had touched. I’m not a lesbian or anything, I guess. I just think that if the person you want to kiss happens to be a boy, then do it, and if the person you want to kiss is a girl, then do that too. Why should it make any difference? I’ve kissed boys and girls. In my opinion, kissing is great. I’m a big advocate for polymorphous perversity, a term I heard on “Fresh Air” one afternoon when

2

Dad picked me up from school, before he turned the radio off. It’s a concept with real punch and

coolness, like the name of a rock band. “Give it up for Andrea Bishop, lead singer with Polymorphous Perversity, performing their number one hit ‘The Anger of the Modernists’!” Applause, cheers, shrieks, the flashing of a million cell-phone cameras, fainting in the aisles.

Anyway, in AP American history a few days ago, doing a two-week segment on immigration and what it means to our country, Mr. Musser, lobbing a soft one, says, “Desi, can you tell us when immigration began in what we are pleased to call the New World?” It’s a loaded question because we all know what he wants Desi to say — “Recent research suggests around 12,000 BC, when Asians began migrating from the Bering land bridge and started the long process of inhabiting the American continents, thus becoming the original people.” Musser has been pushing this narrative on us for days.He believes that 1492 was one of the worst years in the chronicles of the earth and the whole world would be better off if Columbus had not sailed the ocean blue.

I can tell that Desi dressed for this occasion, as if she knew that Musser was going to call on her. She pulled her hair back in a bun, allowing a few loose tendrils to spill out. Black turtleneck, short black leather skirt over black tights. The Desi-touch — black and white saddle Oxfords. She looks divine, like a sort of beatnik/nun.

The funny thing about Desi is, her voice doesn’t match her looks. You would think, just gazing at her with mute adoration, that she would have this voice that seemed to drop from a cloud filled with hummingbirds and sweet panda bears and French toast drenched with warm maple syrup. Instead, when she opens her mouth, out comes a deep, hoarse, crackly voice that sounds as if she’s 75 years old, lives in a cardboard box and survives on a diet of bourbon and

3

unfiltered Camels. It’s sexy, in an outre, rock-star-wife fashion, but also highly unusual. She’s really self-conscious about it. When she stands up to speak, I think Oh what the fuck is going on? She’s supposed to clear this sort of thing with me.

Instead of giving Musser the easy answer, she says, “Dwayne” — Musser’s first name — “I have to consider my response to that question in the light of being a beautiful woman. People think of me differently when I speak, whether it’s my opinion or an observation or just conversation. People find it difficult to see past my beauty to what I’m saying or thinking or feeling. In fact, people find it difficult to believe that I have opinions and observations. If I answer your question in the conventional manner and give you the response you expect, you’ll still wonder where those words came from. You’ll still wonder how there can be intelligent life behind the facade of my face and body. But, see, it’s not a facade. My physical beauty and everything about my thoughts and imagination are inextricably bound together. The medium and the message are one. Let’s face it. Men are afraid of beauty. They punish beauty in a thousand ways. I think the relationship between beauty and fear in our culture needs to be explored. I mean, clinically, by psychologists and sociologists.”

I make a note in the margin of my history book, next to a picture of Pocahontas saving Captain John Smith. “What is envy? What is bliss? Why does beauty matter?” The beginning of a poem. I cross out the first sentence and write: “Who is envious?” I like that. Who? What? Why?

There’s no stopping Desi now.

“To all the people in this school who have asked me out and been refused –” she doesn’t have to look around the room or point a finger — “let me tell you what a date with me would be like. You would trip over your feet. You would mumble incoherently. You wouldn’t be able to

4

keep a conversation going. Every time you looked at my face and body, you would be mesmerized and turned on but also wishing you were back home in your room watching cat videos. Your fantasies and desires would envelop me and cripple you. I’m too beautiful for you. It’s just not worth the effort.”

She sits back down at her desk.

Musser pauses for a few seconds, I guess sort of stunned, then he recovers. He says, “First, Desi, the question is not about you or your beauty or your relationship to your beauty, however true that may be and what your feelings are. However, and second, you’re not a woman, you’re a teenage girl and you’re overthinking whatever you think the issues are. Just get over it. And third, my name is Mr. Musser. Even you, Desi Wainwright, don’t get to call me Dwayne. Few people do,” and we can’t tell if that’s a joke or not. Maybe his wife and kids call him Mr. Musser.

“Yes sir.” Desi glances over at me and raises her right eyebrow. I’ve seen that look a million times. It means, “What a fucking jerk.” Then that look melts, and Desi puts her face down on her arms, on top of her desk, and sobs. The throbbing, choking sound fills our classroom. Musser stands in front, looking nonplussed. (I love that word, by the way. What does it mean to be “plussed,” as opposed to “non”?) His shirt-sleeves are rolled up, not a wimpy two rolls but tight, up over his sinewy biceps. He obviously works out. His wrists bear strange marks, as if he had been tied up and hung from the rafters and tortured in some desert war, but actually they’re tattoos of chain-smoking koala bears dancing in a ring. Musser is definitely our coolest teacher.

A couple of kids come over and stroke Desi’s back or try to hug her when she sits up, but

5

most look away, embarrassed or worse. By worse, I mean, happy, pleased, thinking Miss More-Beautiful-Than-Thou gets what she deserves. Some freak takes a picture and within seconds an image of Desi’s unearthly tear-stained face travels at the speed of light on Instagram.

That night, I’m in my room, working on this new poem. I think of seconds, minutes, hours, days, months, years. What are they? What do they do? Where do they go? How the fuck do I know, I’m only 17! But that’s what poets do, right? Make sense of things they don’t understand or that nobody understands? Using the words available to them? So, what do seconds and minutes do? They pass away, they fade, they … evaporate. Too passive. They slide, they glide, they run away and hide. Don’t start rhyming, girl! Maybe each day tries to tell us something. Maybe we don’t hear. Maybe we don’t listen or we misinterpret the message. I should be thinking about Desi and her sadness and despair, but I’m thinking about this poem, and even as I think about the poem and the words building into images that create a glowing halo of feeling that makes me happy, Desi works her way into it. Desi and her unimpeachable, irreproachable, galactic beauty — and the next words that come to my mind are different: insufferable beauty, intolerable, destructive. And dangerous. Really dangerous. Subversive. For her, for us, all of us, the school, the town, the whole fucking world. How much can we stand? The relationship between beauty and fear! Oh my god, she is so right!

My phone pings. It’s Desi. Can I come over? Oh, my love, yes! I text back, Sure come on. I go to the top of the stairs and shout down to Mom and Dad, “Hey, Desi’s coming over.” Murmurs of assent. What are they doing in their little establishments? My Dad watching “Nova,” something about wolves. My Mom catching up on recipes from the New York Times app. So predictable, so parental.

6

Desi is here in 10 minutes. I hear her say Hi to Mom and Dad, and then she’s up the stairs and in my room, collapsing face down on my bed. She seems to be wearing the same clothes she had on at school, but with a big gray hoodie. She doesn’t say hello or give me a hug for the first time ever.

“I made a fool of myself today, didn’t I?” she mutters into the duvet. “Well, it doesn’t matter. They all hate me anyway.”

“Hey, that’s not true! Nobody hates you! I mean, maybe they’re in awe or maybe really jealous, but that comes with the territory, right?”

“No, they’re scared. I’m like a statue of a goddess, in some white temple in Greece, and if people touch me, their fingers get burned, they burst into flames. I have the taboo on me.”

“Desi, what you did was so brave! It made me so happy that we’re friends.”

“Oh, god, Andrea, you’re so sweet and naive. The innocent poet.” She flops over on her back, long arms out-flung, raises her head and says, “Have you read all these books?”

It’s an old joke between us, so much of my life lived in books, my room like a disheveled library. Cute, bookish, interesting me.

“No, you turd ball, nobody has read all the books they own. There’s even a word for that in Japanese. Tsundoku. Buying books and not reading them.”

Now Desi sits on the bed, cross-legged, like she didn’t even hear me. She runs her hands through her hair, lifts the dark mass, displaying her long slender pale neck, and lets it fall back onto her shoulders. To my mind, her hair falls like thunder or an avalanche.

“What’s most important to you, Andrea? What’s the most important thing in the world?”

I want to say You, my love, you are the most important thing in the world to me, you

7

always have been and always will be, but, strangely, shyness overcomes me, I don’t know how Desi will react. She seems weird, I mean weird bizarre and weird uncanny. What if I confess my feelings and she rejects me? What if she’s offended or repulsed? We’ve always loved each other. We have, haven’t we? I mean, that’s the whole basis of my life. I feel more than ever the vast differences in those degrees and shapes of love. The shadows inside her begin to frighten me. So I say, “Oh, you know, always the same. Words, language, books, reading and writing.”

She nods, and her mouth turns down slightly, a fleeting grimace. “My adorable Andrea, always the writer. Always a little detached. So observant and objective.”

The abyss of her unknowing opens inside me. She has no idea who I am.

“Gosh, Desi, I don’t — well, what is the most important thing in your life, as long as we’re playing this game.”

“A game? I guess so.” She rolls off the bed and walks around my room. The movement of her legs in the black tights kills me.

“I want peace and quiet,” she says. “Dignity and respect. Affection that doesn’t carry dire costs or consequences.”

She doesn’t say You, Andrea Bishop, you are the most important thing in the world to me. She pulls a book from a shelf. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. “You were really into this shit in middle school.”

“Yeah, for a while. I got over it.”

She says, “What is the sound of one girl not clapping?”

I say, “I guess that would be silence.”

“Right. I guess so.”

8

She pulls up a shattering sigh from some bleak tundra inside. Then: “You know all my favorite songs, right?”

“Yeah, sure, of course.”

“Good. O.K., good night.”

She’s skipping down the stairs, and I hear the front door close. I pull the poem out from under a heap of pillows and think about what she said. Costs or consequences. Then: Hunger or thirst. Fear or trembling. Male or female. Cookies or cake. I realize that I’m really hungry.

What Desi did was, she snuck into the garage where Mr. Wainwright keeps his antique Porsche that he drives to meetings of antique Porsche owners, and she used the key she took from the drawer in his study, and she started the car and sat in the driver’s seat and eventually the carbon monoxide killed her.

Some people said how that was a really shitty thing to do, to kill herself with the car her father loved so much, like she was getting back at him for something. I said, Maybe he loved the car too much and his daughter not enough. And some of those people said to me, God, Andrea, don’t be such an asshole. So, in my mind, I kill those assholes and wipe them off the face of the earth.

Next day, Mr. Menendez calls an assembly and tells the school about Desi Wainwright’s suicide, which everybody already knew anyway. That’s why phones were invented. There’s a huge enveloping silence and then some people start weeping and sobbing. What is the sound of one girl not clapping?

9

Menendez calls me to the office. He used to coach track and field. Tarnished trophies with little golden runners and pole vaulters perched on top fill his bookcases. Now it looks as if it would take him a year to sprint a hundred yards. He has soulful eyes, though, and a handsome mouth. I wonder what it would be like to kiss him.

“You were Desi’s best friend, yes?”

I hedge my bets. “Yeah, I guess.”

“Ha, come on, everybody knows you guys were like sisters or whatever. So, you would know all her favorite music, right? Bring me a list of some tunes we can play at her service tomorrow. You can probably get that together pretty quickly.”

Duh. I sit down at his desk, reach across for a pencil and notepad, and start writing. This takes all of about one minute.

“Here’s four. I’ll send you links so you can listen and decide what to use.”

An hour later, he delegates a ninth-grader to my English class, interrupting a discussion about Romeo and Juliet — which is so totally tone-deaf today — with a request to come back to the office.

“O.K,” he says, “I don’t get it, but that’s not my business. First, a definite No on Eilish. I mean, sheesh, how depressing can you get? Second, O.K. on the other three.” He glances at the list. “‘In a Year of 13 Moons,’ ‘The Story,’ ‘Spacing Out.’ They’re pretty morbid, but at least they’re not about suicide. Not that I can tell. You knew Desi best, so I trust you on these. And, hey, who the hell is Beaba Doobee?”

“The ‘Spacing Out’ singer. She’s a Filipino girl. Makes videos in her bedroom. Everybody loves her.”

10

“I’m more a Lyle Lovett man, myself. You know that album, ‘Lyle Lovett and his Large Band’?”

“No sir.”

“You should give it a try. You’d probably like it. I mean, I don’t know for sure, but maybe.”

He swivels his chair around and looks out the window toward the back of the gym and a couple of big blue dumpsters. You’d think the principal’s office would have a better view. Menendez murmurs a few words, and I realize that he’s singing, or trying to sing, in a hoarse, choked kind of voice. Something about a pony and a saddle and a straight-shooting gun. A cowboy song.

He turns back toward me, his face contorted and his eyes red. He’s crying. “This is our first suicide,” he croaks. “We’ve had accidents and tragedies and last year, remember, a gun in Randy Swindoll’s backpack, but never a suicide. Never a girl who killed herself.”

Now I’m crying too. We sit on opposite sides of his wide desk, weeping. I want to go over and hug him, tell him everything’s going to be O.K. even if I don’t believe it. That’s what communication is all about. But it’s drilled into us from the time we start first grade, as sure as we’re taught to shelter in place if there’s a shooter in the school — students and teachers don’t touch each other. I think Fuck it, and go around to his side of the desk and wrap by arms around his neck and lean my head against the top of his head, which smells like coconut shampoo, and we cry together for our dear Desi Wainwright.

The next day is the memorial for Desi. Troops of psychologists and therapists are going

11

to be in the building to help people deal with everybody’s sense of loss and questions about their own sanity or identity or whatever. I get to school really early, the poem tucked into an envelope in my backpack. The dim hallways echo with emptiness, and the light is mellow and watery. I find Desi’s locker and slip the envelope through the air-slots on the door. I lean my head against the cool metal and hear the envelope hit the bottom of the locker where it will lie until someone comes to clean the locker out. Maybe Desi’s parents. Or Mr. Menendez. Maybe Mr. Goolsby, the janitor, he might like a poem. I whisper, as if she were inside that locker, What wasn’t enough to keep you in this world? Don’t you remember the evening we ate strawberries on your back porch and then held hands and went on pilgrimage to a mouse’s grave? That we taught each other how to ride bikes? That the first time we got drunk was when we snuck a bottle of rum from my parents’ liquor cabinet and made some crazy, undrinkable version of banana daiquiris that we drank anyway?

Silence in the locker. A vault of stale air. Not a wisp of a ghost. Here’s the poem:

Who is envious? What is bliss?

Why does beauty matter? Days

Slide away, messengers emptied

Of their purpose. You could be

Drunk on hunger, until you prized

Knowing a thing above its having.

I call it “Wounded Beauty.”

By this time the halls are crowded with kids arriving at school, milling around before first period, a raucous, careless, colorful throng, even in their sorrow. They can’t help being what they

12

are, what we all are, fucked up teenagers. I walk among them, like Walt Whitman in Manhattan, and start kissing people, boys and girls, everyone I see, just kissing like a crazy person, on their sweet mouths. They’re laughing and joking, saying, “Hey, Andrea, what the shit, what’s up, girl?” But I kiss every one of them, every boy and every girl. I kiss them all.

13