From between the leaves and branches of the fruitless mango tree outside my kitchen window, I can hear the roar of the plane and I know she is coming for an unexpected visit. The far-as-the-sky whir of the engine from a few minutes ago, that I should have known was her, in between the noisy sips from my cup of tea, has become a deafening reverberation that only I know and can hear. And a second and a half after I crane my neck to see if it is, indeed, she outside the window, the plane, no longer than my forearm, whizzes through the long, bare branches that thump my kitchen window when they secretly converse with the wind. Through the bars of the window, the tin contraption rolls right in and lands next to the black-as-night table in the center of the kitchen.

Something is up.

This is her choice of commute when she wants to visit. She abhors road travel, trundling locomotives give her migraines, and sailboats that sway and spray her with briny sea foam remind her of tepid, eminently forgettable love affairs. She prefers flying.

She bought this jet from our dad twelve years ago. It was one of his prized possessions, but as he aged, he was starting to feel less connected with his material assets, he said. Pshaw, she had said to him and handed over that month’s paycheck. If you knew what to do with the things you own, you would not be giving them away, she had muttered under her breath, as she walked away with the silver-grey collectible that came with its own hangar that fit perfectly on her mantle top.

She infused the little jet with some of her magic. It can shrink and swell according to the space it has in which to fly in, take off and land. I know my sister needs space to expand to her normal size (she is a few sizes larger and a foot taller than I), so I make room and step back gingerly over the threshold to stand by the low-arched entryway to my kitchen. She gets out of the little plane, takes a deep breath, balloons, picks up her tin contraption, dusts and drops it into her valise, and turns to look at me. She has sprung to her full height and size, her hands on her hips, in the older-and-wiser mode that I have come to know oh-so-well, and before I can catch myself, my guilty right hand has moved right up to cover my telltale grinning mouth.

Wipe that smirk off your face, lard-ass, she says.

We whoop in unison and fling our arms around one another; into the one embrace we know better than we know ourselves.

*

Back when we were growing up, my sister was pure magic. Everywhere she went, she made friends with ease. She was the one everyone loved in both family and friend circles, in gathering places where conversation flowed free, as did resentment, none of which was directed at her. I was the awkward hanger-on, the misfit, the less fortunate sibling who had fallen into emotional disrepair. She was the chosen one who could peer into everyone’s brains, those who had given up trying to be normal, pick a particular thought of self-effacement or criticism and fashion it into a line of flattery that left them feeling like they were something special for years after. The only thing I was capable of was saying the wrong thing at the wrong time to the wrong person – every single time. It was like my superpower.

She was beautiful and she knew it, and she worked it. I was the plainer-by-a-mile also-ran with buck teeth and stringy hair and undisguised adoration for her in my eyes. She could do nothing wrong in my eyes.

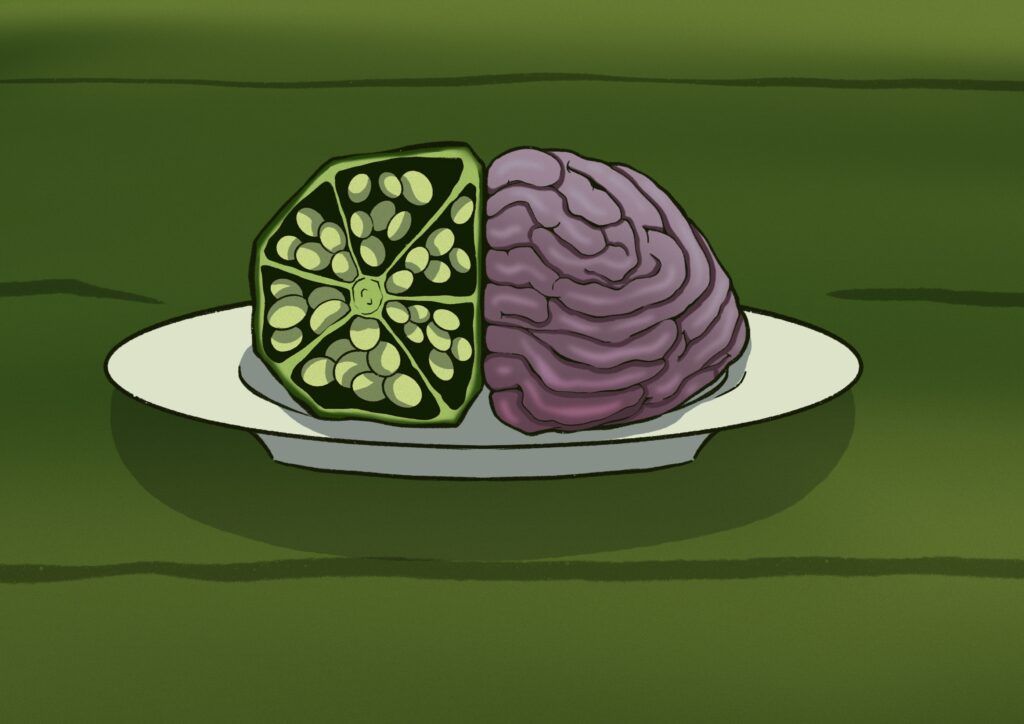

And she loved okra. I was disgusted by the gunk that sticks to every surface – the chopping board, the knife, your fingers, the corner of the sink – but she would pick a just-cut fat okra head, use it to wipe off the gunk from the knife and say, gunk is useful if you know how to deal with it. Okra is brainfood, young one, she used to say to me. What ever will you do without me? Who will teach you all there is to know about this thing we call life after I’m gone? She would chop okra fine and deep-fry them before dumping them into a bowl of whipped yogurt with a dash of paprika or slit them lengthwise and coat them in chickpea flour and shallow fry them in batches or cook them in a smoldering, full-bodied tomato gravy so the gunk got arrested by the tartness and married it harmoniously and serve it to me, but the truth is, I hate okra. I always will. She knows, but she doesn’t care.

And because she knew how much I hated books with lazy titles, she would say, you will cry when I die, but who will cry when you die?

*

She looks a bit off, settled into her lushness on the sofa. I wait.

From where I am sitting, with the sun slanting in through the window to her left, I can tell she has been careless with her bangs. I see the clumsy hand-sewn stitches just under the hairline on the forehead, crisscrossing over and bleeding into one another. This is such an aberration to her visage-careful nature that I know what’s coming is not what I want to hear.

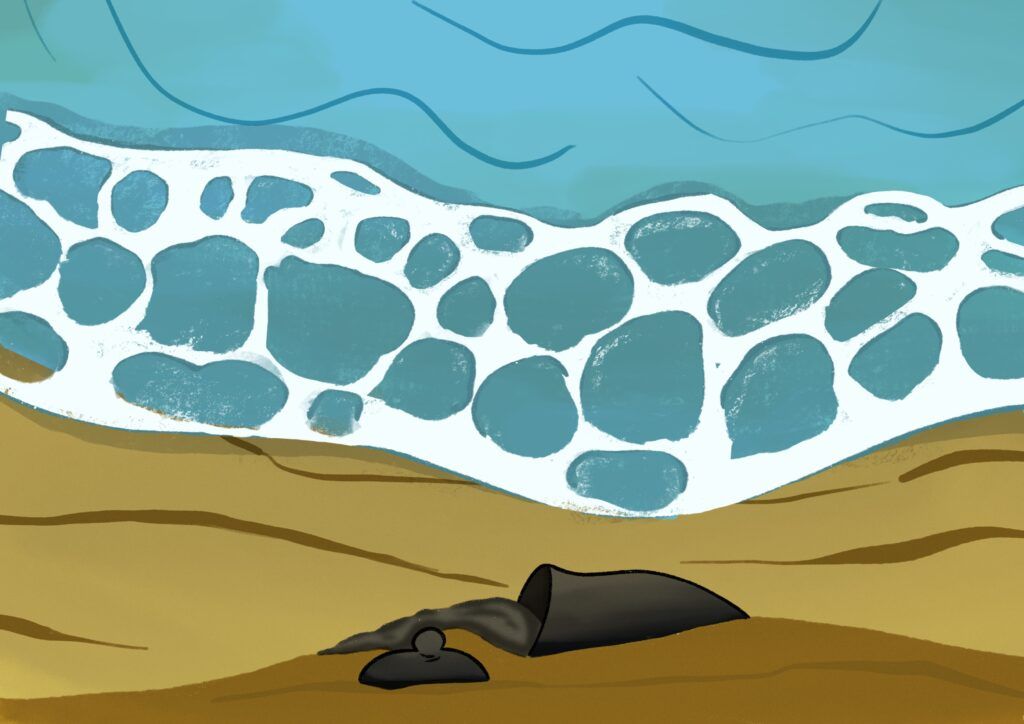

Also, the timing and purpose of the visit seem off. Summer is confession season for us sisters by default. We have a bonding pattern that has not changed right from our adolescent years: we fall in love in spring in the hills, have our hearts broken during the monsoons, write sappy poems in winter, and mend our hearts together by the ocean during the summer, where we bask both in the sunlight shining down from the skies and the light of each other’s non-judgmental, sisterly company. That’s how it has always been.

It is now the dead cold of December when bones and hearts are expected to ache together in misery, and I haven’t even begun writing the mournful dirge of winter #33, but here she is.

I’m checking myself in today, she says. Will you come with me? To the ocean?

*

The summer before last, my usually ebullient sister seemed sullen. As we sat swigging bottles of wine by the sea, watching the new moon embark on its wanton waxing, the conversation turned to – or did it begin there – the end of life. She does not like the term ‘death,’ finds it meaningless in its absoluteness. She told me she wanted me to bury her at sea when it was her time to go. I was vehement that I would not. I told her that I would cremate her as was our custom. I reminded her that Mother used to say if we don’t burn every fiber of the departed, their souls would remain behind in zombie form, squashing all hopes of an uneventful final sojourn to our maker.

She tut-tutted and told me she would rather linger behind as a memory. She said, God is in the small things, young one. Mothers and fathers make their rules up as they go hurtling towards death from life, so learn to trust your own instincts. God isn’t the Incredible Hulk up in the heavens waiting with a whip for your soul’s redemption. He is in the fronds of the coconut tree, in the swirling sea breeze on a balmy summer’s night, in the sip of cool water when you are thirsty, in the dance of the glowworms around hedges, in the dance of flashlights up in the hills as monks walk back to their huts by starlight, their tread gentle even on dead leaves.

And then, quietly, rather uncharacteristically, she said, the sea will come find you when it’s my time.

*

That was also when I came to know that my sister picks her brains. Literally, that is.

She told me then, not without a touch of melancholy, that it was getting harder and harder to stow away memories as absolute, that the mental keepsakes kept changing compartments in her mind and that she no longer knew what was true and what was manufactured by her ageing imagination. She had always been afraid of her brain turning to mush.

Now her brain was indeed softening, like a permanently wet sponge, wasting away towards its imminent fate of the trash bin, collapsing into its own wreckage.

She had begun gathering okra heads and storing them in the freezer, and once every month, the day before she carefully trimmed her bangs herself, she would slice open her head underneath the bangs and shove the frozen okra heads inside to fortify her aging grey matter, because even though she was dying and she knew it, she was fully of the intent that while she was still alive, she would not be the living dead.

*

Of course, I will go with you, I say. When do you want to check in?

Now, she says. There isn’t much time left.

*

For my ninth birthday, she had gifted me a Barbie. I had fallen in love with Barbie’s perfection: those tapering pins, her derriere encased in a tasteful swatch of high-cut silk, breasts lush and hanging high, hair that just begged to be brushed, an ‘I’m-available’ grin pasted to her face, with a wardrobe that was the envy of, well, even me. The lack of nipples did stump me for a while, I admit, but I was willing to overlook the absence of one physical feature for the overall package. I loved my Barbie. Because I just wasn’t she, and wanted so badly to be.

*

I spend all evening with my sister at the hospital. When she sees me nodding off, she says, go home, young one. I will see you in the morning. I’ll still be here tomorrow.

Even my sister cannot stand between me and my sleep, so I place Barbie in her hands and kiss her good night.

You have magic in you, you will see, she whispers in return.

*

I don’t sleep so much as I try to shake off violent visions of all the okra I have spurned over the years. At the crack of dawn, just as I pry myself loose off the sticky hands of phantasmagoric okra and begin to drift away, the head nurse on shift calls me from the hospital. From the gibberish she’s regurgitating into the mouthpiece, I know something’s not right. I tell her I’ll be right over.

Everyone knows me as the sister of the plane woman by now, so no one raises an eyelid – they are mostly shut, anyway – when I try to sneak in around quarter past six. I try and turn the door handle to my sister’s room. I am surprised to find it locked. I knock and tell nurse it’s me.

She opens the door a crack, confirms it is me and peeks over my shoulder to see if anyone else is around or awake. Relieved, she lets me in and quickly shuts the door behind us.

I don’t need to draw the curtain aside to know my sister’s dead.

Nurse hands me the silver plane and a note from my sister that has only two words written on it – FOR YOU, it says.

I ask Nurse what happened. She says, around three in the morning, when she came in to collect a blood sample from my sister, my sister asked her to hand her the plane from her valise and to show up with a mop and a pan in about two hours. Not exactly unused to strange requests from patients, Nurse said she smiled sweetly at my sister – that’s right, sweetly – plunged a needle into my reluctant sister’s arm, drew as much blood as she would need for three tests and left.

When she returned two hours and many minutes later, my sister lay almost motionless, her face sunken into itself on the pillow. Her eyes had rolled back into their sockets, the nose lay deflated, the ears had flopped over and her mouth had sneered back into a skeletal grin.

She had handed over the plane to Nurse, said it was for me, and then breathed her last.

Nurse, not entirely unused to bodily indignity, curious as to what had made my sister’s face crumple like a piece of paper, had stepped into a pile of gunky okra heads. She had transitioned from a sleepless night-induced state of stupor to a slack-jawed state of shock to a stuttering mess ankle-deep in slime in mere minutes.

I ask her for the mop and pan and scoop up all the okra heads from the floor. I cajole her to pry open my sister’s forehead, gently, so I can shove the gunk inside and fill her head up again before the doctor arrives.

Just as I am done tucking in the last piece and sewing her head up as quickly as I possibly can, the doctor knocks briskly on the door and walks in. I somehow manage to make it look like I was stroking my sister’s head and not poking inside it as he mouths well-rehearsed condolences.

I request for her mortal remains to be cremated and the ashes sent to me.

*

For the first time in all the time I have been living, I am consumed by a fervent desire to eat okra on my way home. I go to the grocer’s and pick the tender ones from the bin with my right hand as I continue to wipe my eyes with my left sleeve. I look for the fine flaxen hairs on the surface like she used to, snap the tails off without a sound lest the grocer overhear, dump the ones I want into a bag and head for the counter. Like a zombie, I make my way home with my purchase. The two-block walk feels like an eternity.

At the kitchen sink, I scrub the okra until they shine and dab them with a mound of kitchen towels until I am sure there is no gunk left. Little do I know, for as I slice them fine like she used to, I need to use the heads to wipe away the inevitable gunk from the knife and the board. I then deep-fry them in copious amounts of oil, sprinkling a mix of chickpea flour, cayenne pepper, and salt, spoon by spoon on top, until they are crunchy on the inside as well as the outside.

I wish she were here to eat with me.

I sit where she last sat in the living room, perched on the edge of the sofa seat, the taste of the okra, so far disgusting to me, registering delicious on my taste buds as I chew and cry, chew and cry, chew and cry.

When I am done eating, I sit and patiently wait for her ashes to be brought to me. Yes, we had arrived at a sisterly compromise that honors both my fear and her wish. It doesn’t take too long, it’s all so efficient nowadays. The urn reaches me before sundown. Cradling the urn in one hand and the jet in the other, I head for the beach down the block that makes the walk to the sea the shortest one. I could have chosen the longer route, but the sea seemed to want me to take this one path that’s not yet asphalted. If only I knew how to exhale and shrink like my sister to get inside the plane, I would have, but I don’t, so I walk to the ocean that rises in its grandness as if to welcome me, setting foot on the dirty sands just as the sun’s setting.

I resist doing what I know I must for a long while – deal with it now or later, but later seems like a lifetime away right now. I set the urn by my feet, kneel, and build a mound of sand. As if it were more delicate than spider silk, I lay the plane down and by the light of the fading sun, squint to see if there is something inside, a secret message my sister has left me before she passed on. By the fading light, I notice a groove all the way around and gently pry open the top part by the tail.

Inside is beautiful golden-haired Barbie, with the bangs trimmed fashionably around her berry-sized head. Even before I reach for her hair, intimately acquainted that I am with my sister’s penchant for the morbid, I know Barbie’s head has been cut open and clumsily sewn up. What I am not prepared to see is a piece of my sister’s brain, like a shriveled chicken fetus, the one uncremated piece of her, inside Barbie’s head.

I pick it up, tears gushing forth and pooling around my legs. She knew.

I peer closely at that little piece of scrambled-egg-like grey matter in my hands and I find everything that has ever mattered to me: our songs, our shared disappointments, our seaside vacations, our sibling rivalries, our concealed secrets, our sins, our redemption, our failed diets and relationships, our closet-loving skeletons, our chronic self-ruination and subsequent spiritual rebirths, our exacting expectations of life and its unsympathetic, crushing defeats.

Unbeknownst to me, my left foot has gently tipped over the urn. In wonder, I watch the grey soot spill into the welcoming waves, whispering their soothing lullaby to the sun as he sets. And then, great sobs rack my being, humongous heaving sobs, as I cradle the last mortal piece of my sister in my palms. Tears cascade down my cheeks settling into gushing white rapids, and my sister’s words come back to me – the sea will find you when it’s my time – and swathes of grief pool around my ankles, rise to my knees, encircle my hips, envelop my breasts, and welcome my face into their cocoon of understanding, before carrying me and my sister out to sea.