It was late September, and Rebecca Whitfield readied herself for work. She selected a light coat from the hall closet, an olive number that reminded her a bit of a field jacket, but which was only a single layer and therefore not very useful in Massachusetts. She had bought the jacket on impulse, and now felt a strong need to wear it during the brief window that the canvas-y material was appropriate. As she shrugged into the stiff sleeves, her eye caught, for the first time in quite a long while, on the framed embroidery hanging to the left of her front door.

She rarely noticed it anymore. Perhaps because it hung in the space that was blocked if the door was open. Or perhaps it had become so familiar to Rebecca that her gaze passed over it, her mind assuming that everything was as it should be, with no cause to really see. She paused a moment and studied the embroidery, the sapphire words stitched in cursive by her mother’s steady hand.

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

The quote was Aristotle, although Rebecca’s mother must have run out of room because the words stood alone, attributed to no one. It was a bit strange for a gift, and Rebecca had pondered its meaning for several days. Eventually, she decided the gift had been a tacit endorsement of her life which was, at least in her mother’s eyes, simple. No husband, no children, and a job the family didn’t entirely understand, and was thus reduced to its simplest description. Rebecca works at a library, her mother would say, prompting Rebecca to explain that yes, she did work at a library, but on a university campus, and she wasn’t just swiping cards and shelving books. Her job was far more complicated than that and, actually, a master’s degree was required to even apply for a position like hers.

Rebecca locked her front door and began the walk to campus. The university where she worked—the very same university she had attended as an undergrad—was only six blocks from her house, and as she walked along the neat sidewalk she thought again of the embroidery. She tried to remember when her mother had given it to her. It had to be close to three years ago now, which would mean it had been a thirty-fifth birthday gift. That was also right around the time her parents had stopped pestering her so much about settling down. Not that her mother and father had based their decision on her age. Rather, Rebecca suspected they had simply grown weary of repeating the same conversation. Not to mention Rebecca’s little sister, the youngest of the five Whitfield siblings, had gotten engaged that year, and her parents were apparently appeased by their eighty-percent success rate.

Large families could be just as lonely as small families, or even no family at all. This was a truth that many people did not know and, indeed, often resisted when Rebecca said as much. She understood the counterarguments. Because how could one be lonely amidst such bustle, with family gatherings that better resembled a mid-sized church service? But no onein a large family was ever the focus for long, and in such an environment someone like Rebecca, shy and reserved from childhood, was relegated to the background, a sort of benevolent aunt window-dressing.

Rebecca’s obedient catholic siblings had already given their parents ten grandchildren, and even for a family accustomed to chaos and commotion, it was starting to verge on too much. Rebecca, for her part, was childless, and not entirely unhappy with this. In fact, in her heart of hearts, perhaps Rebecca was quite pleased with this. She had witnessed first-hand the demands made by her nieces and nephews and it seemed…well, excruciating. Rebecca’s days, on the other hand, were marked by calm diligence, beginning with her morning routine, which she had honed to be as relaxing and pleasant as possible.

Her evenings were equally as lovely, a time to unwind, unburdened by the need to rush home from work, or deal with some ghastly overdue science project. She would walk around the university track, or cook dinner, or meet the girls, or simply return home to her quiet sanctuary. If, every once in a while, Rebecca had the nagging sense that something was slightly wrong, she brushed the feeling off. And it wasn’t that anything was wrong, per se. It was rather an odd notion that things had stagnated.

It was difficult to describe, this feeling of stagnation, and made more sense when discussed in the context of Rebecca’s friends and acquaintances, the people that made up her extended social circle. For so long, it had felt like they were all on the cusp of something great. There were the authors, working on novels that were sure to be bestsellers. The stand-up comedians who were doing their time in the dingy clubs of the eastern seaboard. Bands that formed and reformed like molecules, just waiting for the right combination that would catapult them to fame.

They were not famous yet, but rather…famous in waiting. So full of promise and ambition that success had felt inevitable. But slowly, as their twenties had dissolved into their thirties, as the idea of sleeping on couches became significantly less desirable, as things like rent and health insurance became significantly more desirable, their prospects had just seemed to fizzle out.

Rebecca herself was not immune. Once upon a time, as an undergrad, she had been the darling of the UMass history department. It was a foregone conclusion that she would get her PhD, and then it was only a matter of time before she was tenured, an expert in her field, her photo gracing glossy covers in chain bookstores. She was reminded of this alternate future each morning when she passed the walkway that led to the history department. She glimpsed it now, the sun-dappled arch, and hurried towards the library.

What had happened, then? For starters, her master’s program was not the academic haven she had expected. Her dumpy apartment did not match up at all with her visions of mullioned windows and wood paneling. And worse, somewhere in the second semester of her first year, the sense of mystery and wonder that history had always awakened in her seemed to evaporate. Her specialty, pre-revolutionary American history grew dull. It felt like everything had been discovered already, and they were now parsing tiny details that no one—outside of a miniscule community of PhDs—cared about.

And then the already tenuous academic job market took a nosedive. She didn’t particularly want to be an adjunct professor at a college somewhere in Tennessee and so she decided to abandon her PhD dreams and apply for a master’s in library science. While they might not have the Indiana Jones-laced glamour of a historian, librarians, at least, could find a stable job. This transformation played out all across her social networks. The authors began careers in human resources, the musicians became teachers. Even the radicals, the ones Rebecca thought the least likely to conform, took tame jobs at non-profits.

Rebecca would admonish herself then. This was just growing up. They were approaching forty; the time for naïve dreams was over. And she worked at a place that she liked, wasn’t that miracle enough? She had a circle of strong, supportive friends. She had her beloved choir, at the catholic church. And who on god’s green earth had decreed that a small life, a pleasant life, was not something to be desired? She wanted to tell her nieces and nephews that they should strive to be like her. She had known the truth before her mother ever embroidered those words and given them as a gift.

Her first stop of the morning was Holly’s office. Holly was her confidante and best friend, and the ringleader of their little library cohort, which they abbreviated as LLC in the group text. It wasn’t as exclusionary as all that of course, and had grown over the years. Tiana, Leah, and Bethany were all librarians, but Celine and Christina were professor’s wives, and Addison, recently divorced and engaging with the group with renewed vigor, worked in admissions.

Rebecca walked through the familiar, gray carpeted halls of the second floor, and found Holly at her desk, eating a bagel and staring at her phone.

“Eddie,” Holly said through a full mouth, and pointed at her phone.

Holly, younger by two years, had been as single as Rebecca until she met Eddie Cooke a few months ago. Eddie was an Amherst native and realtor, the sort who had his name and logo emblazoned on his car. Holly had offered to set her up with one of Eddie’s friends, though Rebecca had politely declined.

It was not the case that she didn’t want a partner. Truth be told, sometimes she desperately wanted one. It would be nice to have someone to travel with, to help assemble furniture, to accompany her to the occasional nerve-wracking doctor’s appointment. She was attractive enough, and she had progressed nicely in her career, but it was difficult, nearly impossible, to date in a college town. The men of Amherst were either dangerously young, dangerously married, or townies. And Rebecca was absolutely, definitively not a townie. She knew how this made her sound, and she would never confess such a notion to Holly or anyone else. But Rebecca couldn’t help it. She had two master’s degrees for crying out loud—she was an academic.

Holly asked, “You’re sure you don’t want to get dinner with me and Eddie? I’m trying to see if Celine and Tony want to come too.”

“Can’t,” Rebecca said, relieved to have a ready excuse. “I have choir practice tonight.”

“Again?”

Rebecca had joined the choir three years ago—well technically, she had auditioned for it and been admitted as an alto—and it was not a light commitment.

“The fall concert is coming up,” she reminded Holly. “It’s our biggest show besides Christmas.”

“Right, right,” Holly said distractedly, staring at her phone again.

Rebecca said goodbye, filled her mug from the communal coffee pot, and walked into her office. Sunlight streamed through her windows and below, students swirled on the emerald lawns. She settled into her desk chair, content, safe, happy in this bastion of learning and civilized quiet.

*

September slipped into October, and soon the semester was in full swing. Rebecca loved this part of the school year, when the structures guiding campus life were firmly intact. The ends of the semesters were always disruptive, the students so stressed with finals, and the air filled with uncertainty. But for now, there was routine, as crisp and predictable as the New England fall. It may have been that the semester passed in the same agreeable, if unremarkable, way it did every year. If only two things had not happened.

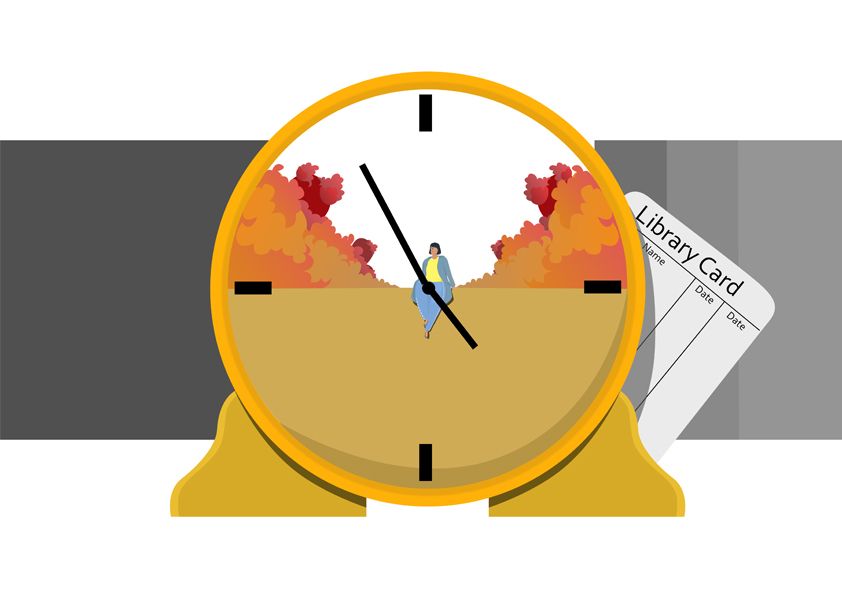

She thought of them as natural disasters, like an earthquake and a tsunami. They were inextricably linked, one to the other, though each devastating in its own right. First, there was the concert. This was the earthquake. Then the email. This the tsunami. And together, they laid ruin to Rebecca’s previously pristine life.

*

On the day of the fall concert Rebecca woke feeling nervous. It was the same feeling as when she had to wake early to make it to the airport on time, stomach tight and appetite gone. Fortunately, the workday was busy, keeping her mind off the evening. It was only at the end of the day, just before she left the library, that she was able to fire off a quick reminder to her friends. She only had an hour to get home, shower, and be at the cathedral in time for rehearsal, and so she opted for a group email, rather than individual texts.

Once the show was finished, and the applause had died down, and she could finally catch her breath, Rebecca followed the others to the dressing rooms. She hadn’t been able to pick out her friends from the stage, but this was not unusual. The nave was large, and the lights quite bright, making it difficult to see past the first few pews. She changed out of her robe and turned her phone back on.

The messages arrived in a series of bright pings. Some were replies to the email. A couple of her friends had texted her directly. It didn’t matter the medium. The messages were all the same. Lame excuse after lame excuse. Even Holly said she forgot she had dinner with her parents. The adrenaline flooded out, leaving Rebecca feeling deflated and weary as she trudged through the hallways. The nave was busy with the usual post-show flurry, but she suddenly wanted nothing to do with any of it. The other members of the choir, posing for pictures with their own little bands of supporters, didn’t even notice when she left.

She did not wake with any intention of sending the email. A number of things converged the following morning, however, to make her sit down at her computer and punch out the message before she even showered. To start, she was hungover. She was not one to use substances to cope, but she had been feeling rather abandoned, and had uncharacteristically finished almost an entire bottle of wine. She might have gotten over this with an aspirin and a coffee, but then she walked into the kitchen.

She stopped in the doorway, and cursed her previous self, who had left behind a dirty room and too much to do. Her spaghetti dinner was still in the sink, where she had drunkenly abandoned it, the noodles brittle and the sauce congealed. Her compost bowl sat on the counter, emitting an unpleasant odor, and the plastic trash bag, which she had taken out of the bin but not walked to the street, had settled against the door like a lumpy, melted snowman.

This was one of the worst things about living alone. As much as her friends complained, as useless as they made their husbands out to be, Rebecca knew the men helped a not-insignificant amount around the house. When you lived alone, there were no surprises. No one magically took out the recycling or did the dishes. If you left a mess, it simply waited for you. It was the sad, forgotten state of the room that Rebecca found so upsetting, much more so than the prospect of actually cleaning up, which would take no more than ten minutes.

She ignored the kitchen and marched to her computer. She began an email to her errant friends, saying that she had missed them, that she wished she had known of their conflicts before giving them her tickets. Contrary to what some might think, she knew the exact tone of her email. She hit it perfectly, in fact—that wounded, cheerful determination that said you hurt me, but I’ll soldier on. It felt good to play the victim.

By noon, Rebecca had received seven (seven!) responses, one from each of her friends. Holly even came by in person, armed with a vanilla latte for Rebecca as well as an apology. Rebecca graciously accepted both before quickly changing the subject. She wasn’t one for overkill. She ate lunch outside, the autumn sunshine lazy and buttery, and by the end of the meal she had entirely forgotten her hangover. Indeed, the day seemed to be turning around. She brushed her skirt off and went to find Holly.

They had installed new software last week—they were forever foisting new software upon the library staff—and she and Holly had agreed to learn it together. She found Holly at her desk, the program already up on the monitor and her friend’s brow furrowed in frustration.

“I swear they do this on purpose,” Holly said without preamble. “They’re torturing us just because they can.”

Rebecca dragged a chair behind Holly’s desk, though before her friend could expound on the torture, one of the student employees beckoned to Holly from the open door.

“Take a look at your doom,” Holly joked, as she went to help the girl.

Rebecca sighed and leaned forward to study the screen. She was trying to make sense of the search hierarchies when an email popped up in the corner. It was a reply-all from Addison to her own email. She clicked open the message on instinct. Holly wouldn’t mind, and it didn’t matter since the email was to her as well. Only, it wasn’t.

Rebecca felt a wave of heat wash over her. She was trying to take in too many things at once. She scrolled down quickly, found her original email from the morning, and then scrolled back up, her breath growing shallow. The email was indeed a response to hers, but she had been left off the reply-all. No, she had not been left off, she had been actively removed. The response was short, just a couple of brief sentences, though each stuck a knife in Rebecca’s gut.

Yawnsville…Holly had the right idea watching Love Beach instead. See you guys at the Christmas concert I guess (note to self: bring flask).

For the first time in her life, Rebecca felt that she might actually faint. If Holly came back now, Rebecca was worried she wouldn’t even be able to form words. But she could still see Holly at the other end of the hall, talking animatedly. Rebecca read the message again and again, trying to process each fresh, horrifying truth. Holly had not been with her parents at all. Holly, her closest friend in the world, had chosen trash reality TV over an event Rebecca had made clear was important to her. Rebecca rose and disappeared into the stairwell, the email still up on Holly’s computer.

She walked without paying any attention to the route, carried along by sheer muscle memory, and when she arrived at her front door, she was quite shocked to realize she was home. She unlocked the door and went to her laptop, where she wrote her boss an honest email about feeling ill and needing to leave early.

She had never felt so betrayed. It was not that her friends had lied to her—well not entirely. It was the disdain, so evident in Addison’s casual reply. She could deal with being an annoyance. She could not stomach being an annoyance and utterly oblivious to such a shortcoming. By four o’clock she was deciding between opening another bottle of wine or eating her weight in pizza, when a hesitant knock came at the door. She opened it to find Holly, an expression of mock embarrassment and sympathy on her face.

“We feel awful,” she said, preempting Rebecca. “It was a joke, and I’m sorry you saw that. I hope you’re not taking it to heart.”

Such wording, Rebecca thought. I’m sorry you saw that. Holly wasn’t sorry that she had humiliated her closest friend, she was just sorry that Rebecca had born to witness to their cruel little comments.

Rebecca’s expression must have given her away because Holly’s face became serious, and she asked, “Are you ok?”

“No.”

Whatever momentum had carried Holly here, this reply killed it. Holly was hoping for an easy out, and she was not going to get it. Rebecca turned and walked into her living room. She didn’t want to invite Holly into the kitchen, so she stopped at an awkward point halfway through the room and turned around again.

“Were you really watching Love Beach?” she asked.

“What?”

“The email said you were watching Love Beach.”

“I don’t know,” Holly said. “Maybe. I can’t remember.”

“But you weren’t with your parents.”

Rebecca phrased this as a statement, and Holly looked exasperated. That wasn’t fair. Rebecca should be the one to be frustrated, what with learning that her friends found her hobbies boring, her requests burdensome, and her overall life pathetic.

“Look, Rebecca, I understand you’re upset. But it’s not a big deal. It was really just a joke. You’re taking it too hard.”

“It’s not a joke if I’m not in on it.”

“Honey,” Holly said, “you have to know that some people don’t share your love of choir music. I mean we want you to do it, duh. It makes you happy. But everybody is working, everybody is busy, and the concert was on a weeknight. It would be like if I asked you to come and, I don’t know, watch me swim laps or something.”

“I would go if you asked me to,” Rebecca said primly.

“So, your friends skipped a concert,” Holly said. “Can you try to have a little perspective?”

“Excuse me?”

“I mean, is this really the worst thing that could happen?” Holly was trying for kindness, but she was veering dangerously close to obnoxious. She continued, “Is it worse than being robbed, or getting sick, or a family member dying?”

Rebecca narrowed her eyes and said, “Thanks for the perspective.” And then she uttered a word that she had never, in her adult life, used against another woman. She had said it, of course, many times over the years. But that was always in lighthearted or subversive ways, twisting the word around to empower or to joke. She didn’t use it that way now, however. She said, voice sharp as acid, “I don’t need your condescension. Bitch.”

What followed was a stunned silence. Stunned outsized to the word itself, because was that an insult anymore, really? Some might argue it was harmless, rendered toothless or even obsolete, though it certainly didn’t feel harmless now.

“I should go,” Holly said finally, and walked to the front door. It closed a little too hard, leaving Rebecca standing in that odd place on the rug.

Rebecca went to sleep without dinner, her stomach still churning from the encounter. She feared she would not sleep well for the second night in a row, though the emotional turmoil of the day had left her exhausted, and she fell into a dreamless sleep. When she woke, her first thoughts were of embarrassment and guilt.

She couldn’t face Holly, nor her other friends, whom Holly had no doubt spoken to, and because it was Saturday, she stayed in bed far longer than usual. A full night of sleep had given her perspective—not the kind Holly had preached in her holier-than-thou speech—but the sting of betrayal had faded, and she was feeling rested and more level-headed.

Rebecca wanted to show them. Holly and the rest of her friends. But it wasn’t revenge that she craved. It was something else, and it took a long time for her to put her finger on it. She wanted to show them that she didn’t need them. That she was so far above their pettiness. She wanted them to feel insignificant, mundane when they compared themselves to her. These disasters had wrecked the delicate ecosystem of her life. She would have to go about salvaging what she could. Or, she thought, she could pack up and simply move away.

*

She told no one of the acceptance. She knew it would come in email form, though in her mind Rebecca had envisioned and indeed, longed for, the old process, the excitement of opening an envelope. Still, it was thrilling when the email at last came across on an overcast morning in March. She knew before she even opened the message that she had been accepted. It felt like there was magic in the world again. It felt like there was magic in her. She stared at the text for ten, twenty, thirty minutes, hardly daring to breathe. She, Rebecca Whitfield, at thirty-eight years old, had been accepted into one of the country’s best history PhD programs. Not only this, but she had gained acceptance with absolutely no help from anyone, and done so in a relatively short period of time. It had required a herculean effort—digging up her old thesis, studying frantically for three weeks to take the GRE in time, producing a new, polished writing sample, and so much more.

She waited to tell her friends until they were all together in person. She and Holly had reconciled. Of course they had. It would be impossible to work in such close quarters and not be on speaking terms, and so after a tense week both women relented, the apologies coming quickly and profusely. She knew Holly had told the others, but they all—Rebecca included—pretended that nothing had happened. There was no way to address it without excruciating awkwardness, and besides, Rebecca had greater things to worry about.

Two weeks after her acceptance, she gathered the girls for brunch at a local café. Or rather, most of the girls, because Addison couldn’t make it. And actually, Rebecca wouldn’t have to deal with Addison for much longer. She had taken a job at a tiny college outside Baltimore to be closer to her family post-divorce, and would be moving just as soon as the semester was over. It would seem that March was a lucky month for Rebecca all around.

Rebecca waited until they had settled in, sipped their mimosas, and ordered their breakfasts, before telling the group she had an announcement. It was received with all the shock and awe she had expected.

“Will you really go?” Holly asked, once the clamor died down. There was a strange expression on her face that Rebecca had never seen before.

“I don’t know yet,” Rebecca answered. “I’m still considering.”

She couldn’t keep the smugness out of her voice, not that she really tried. She finally had something that no one else did—she had options. Unlike the girls at the library, or Celine and Christina, who were forced to move around the country for their husband’s jobs, or Holly who, when she arrived at brunch, had been dropped off in a gray sedan bearing an embarrassingly huge picture of Eddie. But Rebecca—well she was back to being one of those ambitious academics, standing once more on the cusp of fame.

When Rebecca returned home after brunch, she nearly contacted the program head to declare her enrollment. But, because she was just a little tipsy, she decided to wait until the evening. She took a long nap and then when she awoke, she felt that Sunday night was not the right time to send such a momentous email. It came to be, over the course of the next three weeks, that there was never the perfect moment.

When she had first been accepted, Rebecca had printed off a copy of the email so that she could have something tangible to hold. She examined the paper most evenings, partly to remind herself of what she had done, and partly because the deadline to enroll was creeping ever closer. For a long while her acceptance had felt like an abstract concept—something she had accomplished and was finished with. But now, as the days slipped away, she began to think of all the real ways that her life would change.

First, she would have to sell her house if she moved to Virginia. The thought made her a little sad. Maybe even a little queasy. And while the promised stipend was generous by graduate school standards, it was still less than half of her current salary. Five years—at the very least—was a long time to live with such a pay cut. There would be no more satisfying days at the library, no more walks around downtown Amherst. And no more Holly. The email incident felt very far away now. Addison leaving had provided a way out, a salve for the whole situation, and the LLC had fully recovered. These friendships that Rebecca had poured so much effort into, some stretching back over a decade, would be snuffed out by the distance, the rigors of her new life.

The morning of the deadline, Rebecca sat at her desk and studied the printout. She would have to make a decision by the evening, and she placed the paper in the very center of her desk. She then got ready for work, and because it was unseasonably warm, she selected a light jacket. Her field jacket, as she sometimes called it. She tried to remember the last time she had worn it. Some day in September, she thought, before the chill arrived. She shrugged into the jacket, and her eye snagged on the framed embroidery hanging by the door. She would need to clean that sometime soon, she mused. She took the hanging off the nail and examined it. The glass was dirty, and the frame needed to be dusted. Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

She stood in the hall a long while, making herself later and later for work, though she wasn’t thinking of that. Eventually, she hung the frame back on the wall, returned to her desk, and neatly placed the paper into the bottom drawer.