Ezra and Benji couldn’t have been cut from more separate molds. Ezra was graceful despite his averageness: normal in height and build, full-faced and quick to smile. He had beautiful teeth and even more beautiful eyes of a clear, mischievous gray. His fingers were long. He had a propensity for pushing them back through his hair, working through knots that never looked particularly tangled in the first place. He was chameleonic. There was no social situation Ezra didn’t know how …

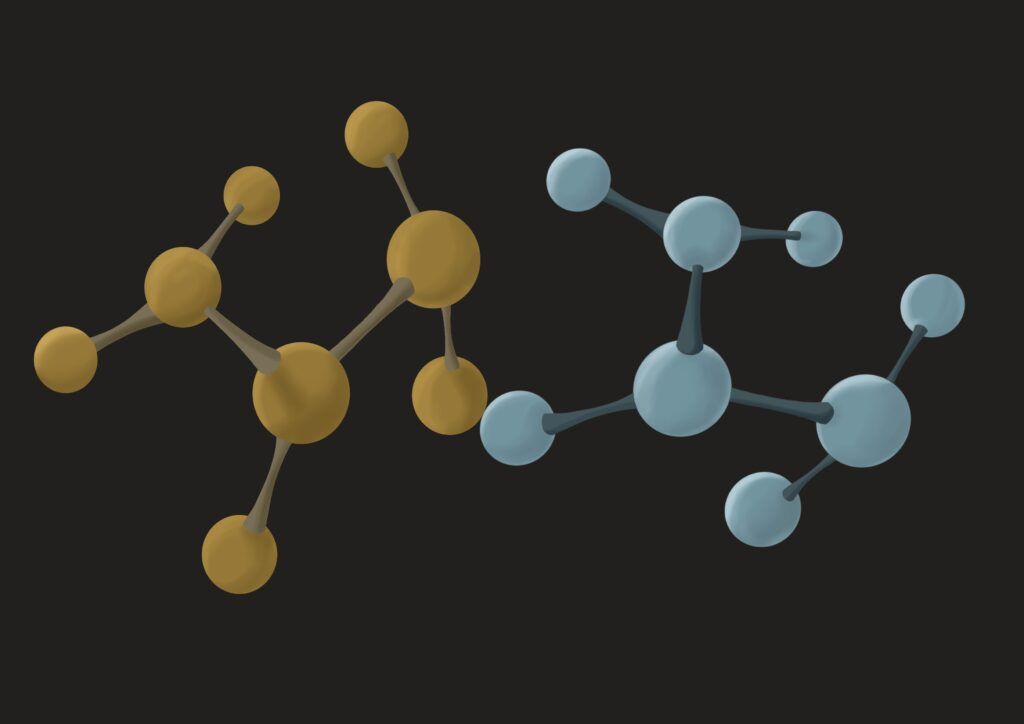

Like MoleculesRead More »

Interested in non-clickbait content? Become a member today.

You'll get access to:

- All content

- Comic Books

- Personalized cartoons

- Member credits in our videos and much more!

Become a member

Already a member? Log In